Historical and museographic tour of the collection

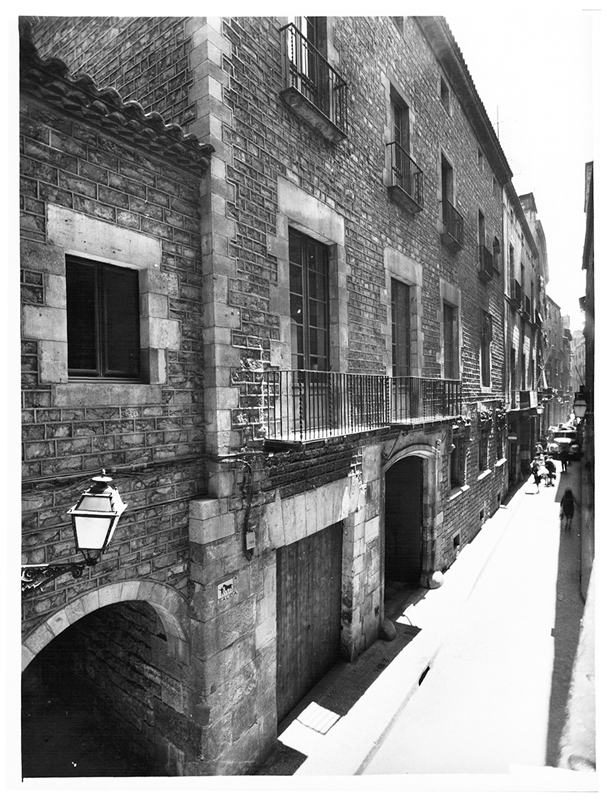

On 9 March 1963, the doors of the Palau Berenguer d'Aguilar in Carrer Montcada in Barcelona opened. The public could now visit the recently inaugurated museum, initially called the Sabartés Collection.

Its history, however, began much earlier, in 1955, during one of the annual visits that Picasso's secretary and personal friend, Jaume Sabartés Gual, made to Barcelona.

It was then when Sabartés began talks to donate his private collection to the city with which Picasso had forged close ties during his youth. Among the conditions Sabartés imposed was that his collection should be the seed of the artist's future monographic museum; Picasso, for his part, undertook to increase the museum's holdings with personal donations.

The negotiations were long and complicated. Picasso was not exactly a friend of the Franco regime. Still, Sabartés was not alone: he had the support and efforts of a whole group of people who helped him present the museum project to the political authorities of the time. On 27 July 1960, at the Barcelona municipal plenary session, it was agreed to create the Pablo Ruiz Picasso Monographic Museum and to fit out the Berenguer de Aguilar Palace (a building the City Council had acquired in 1953) for its future location.

|

The link between the Gothic Quarter and Picasso is a factor that was undoubtedly taken into account. Between 1895 and 1904, its streets witnessed how a young Picasso developed personally and professionally: it was there that he furthered his artistic training, had his first workshops and frequented the emblematic premises that facilitated his integration into the social and cultural life of the time.

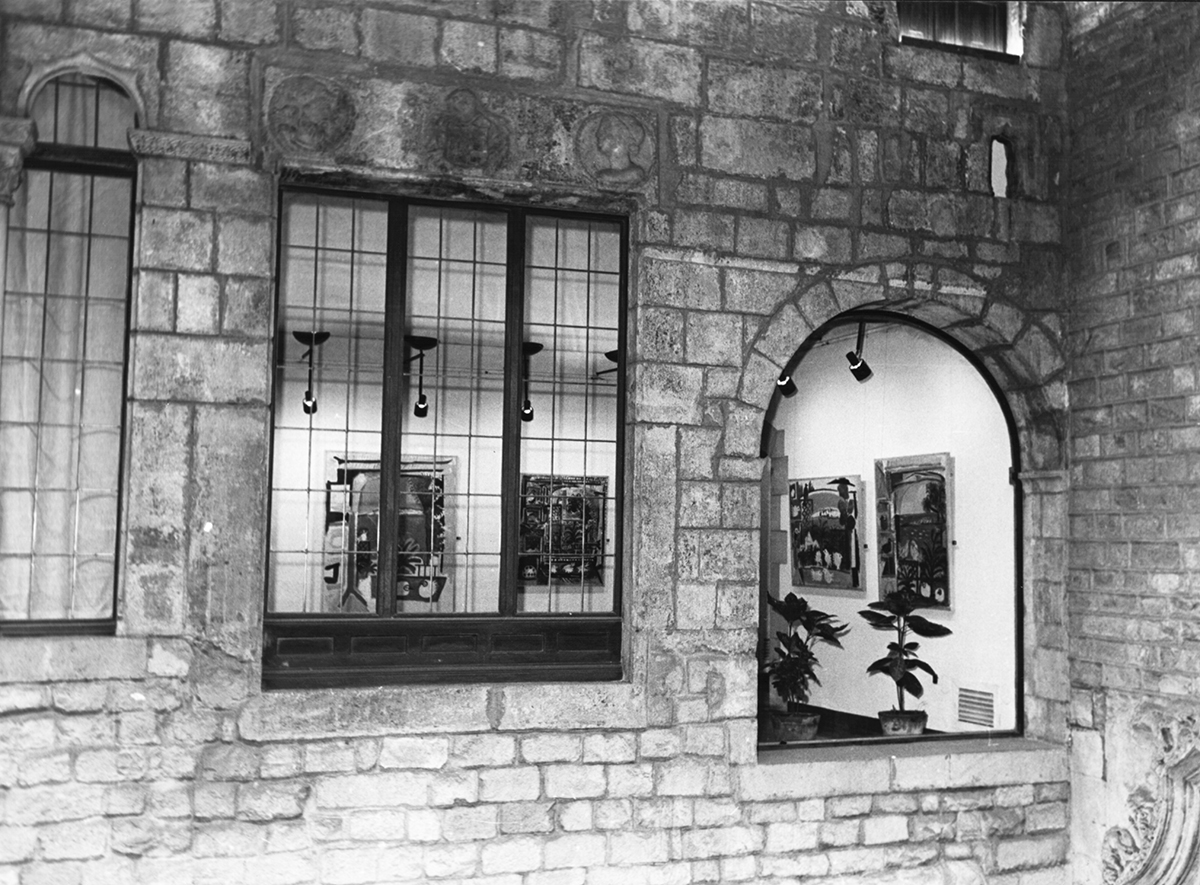

However, the site chosen for the museum was also part of a strategic municipal plan aimed at halting the degradation of Barcelona's Gothic Quarter and restoring it to the splendour of the past, when it became one of the most historically and heritage-rich areas of the city. As early as 1947, Carrer Montcada had already been declared a Historic-Artistic Monumental Site because it contained numerous Catalan Gothic civil style buildings that had to be preserved and protected.

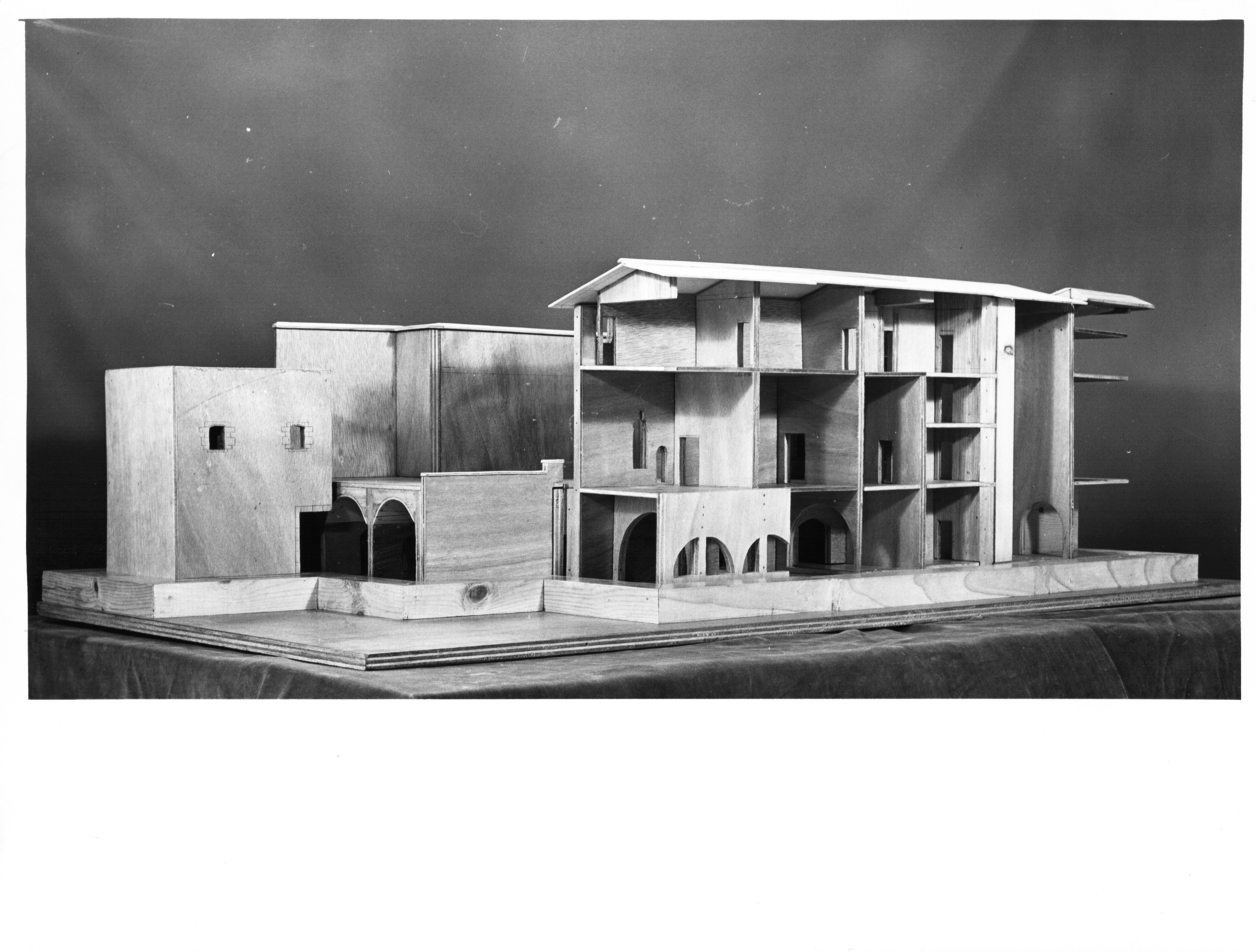

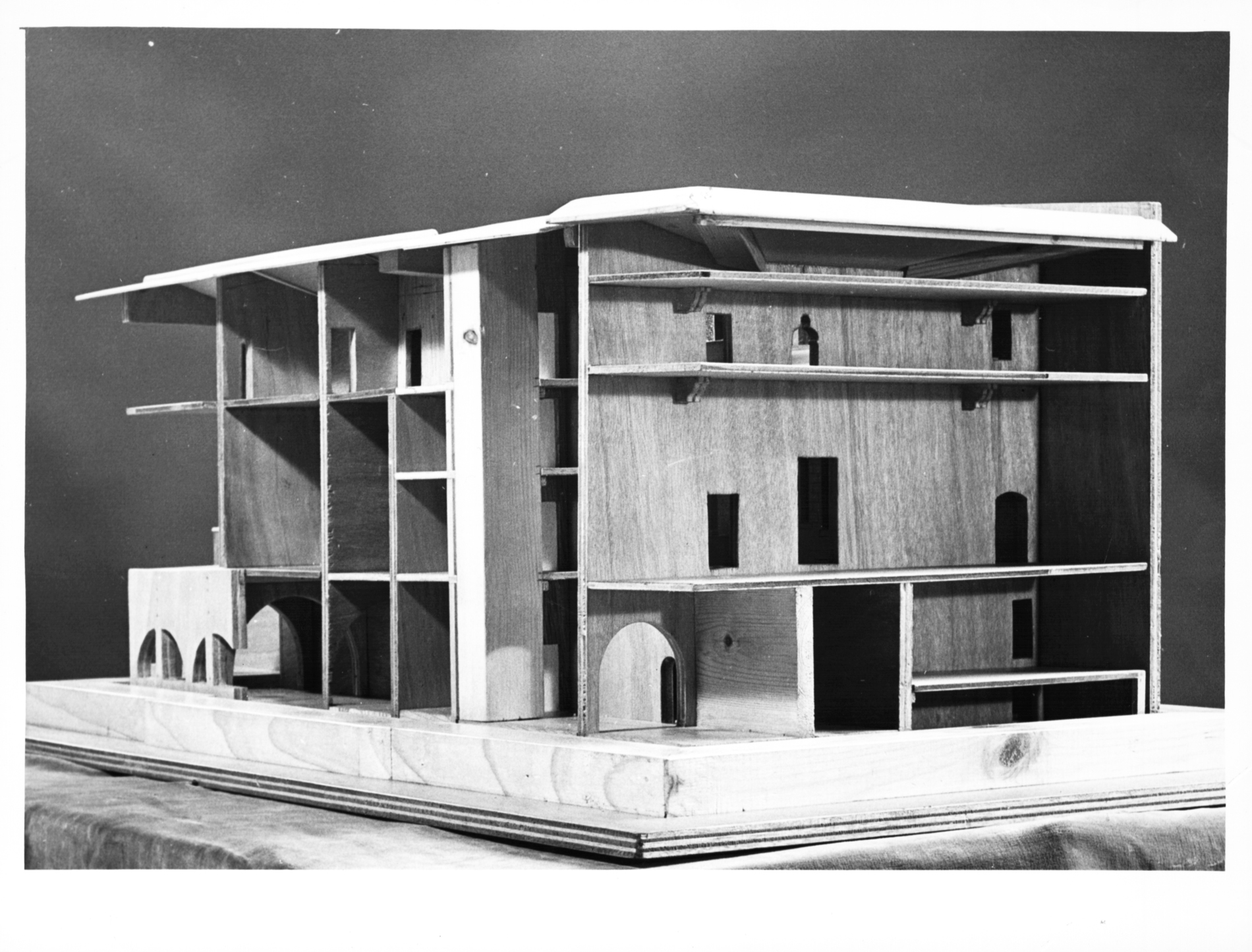

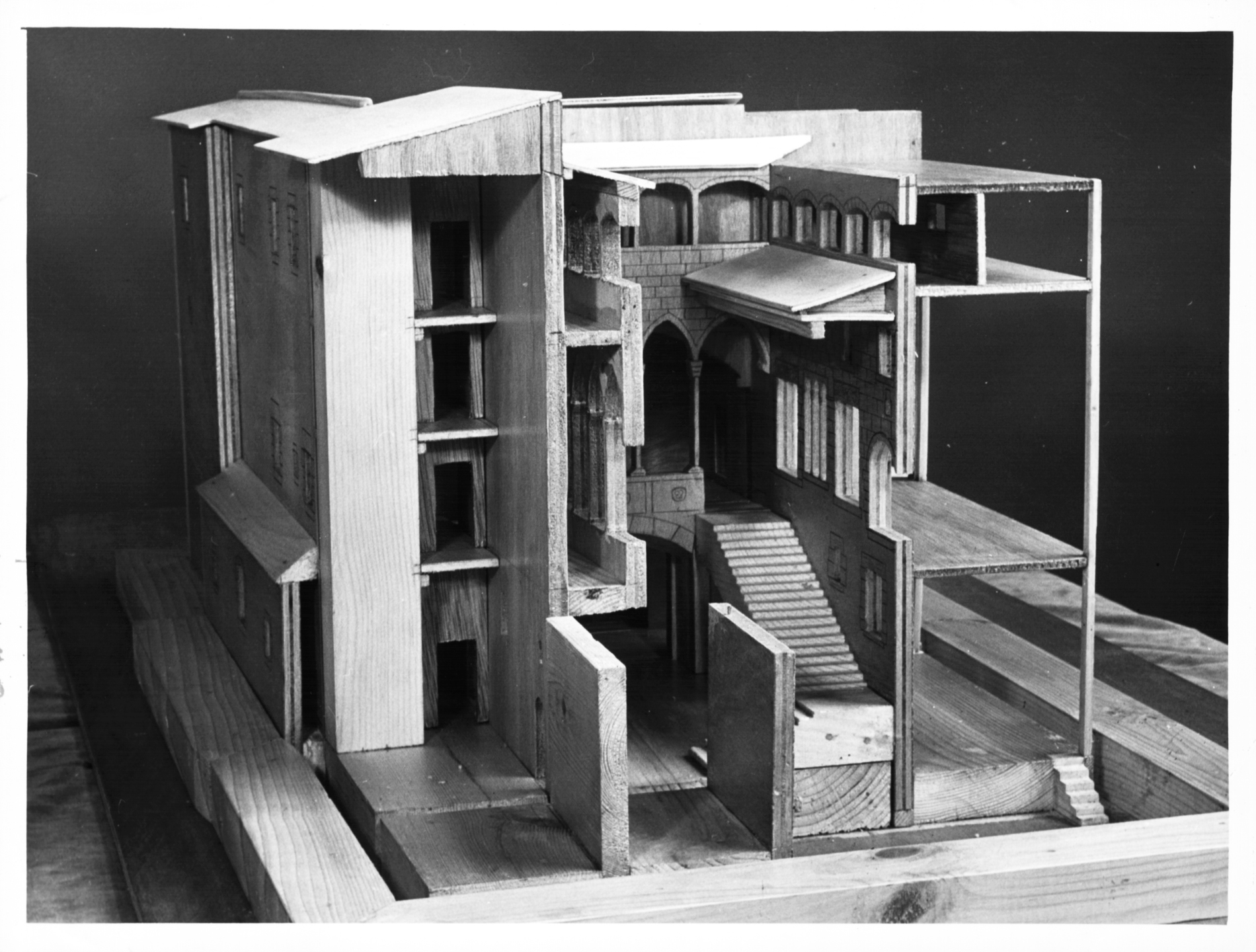

Renovation work on the palace began in 1960. The budget and difficulty of the project, already high at the outset, were only increased due to unforeseen events: structural instability of the building, absence of foundations or the apparition of unexpected heritage elements, to name a few.

|

|

Today, we can find some of the heritage elements that take us back to these times of splendour while walking the exhibits: the coffered ceilings of the Aguilar and Mauri buildings; the neoclassical hall from the 18th century located on the first floor of the Baron de Castellet building; or the late 16th-century coffered ceiling, decorated with hand-printed and illuminated woodcut paper on the ground floor of the same palace. The mural paintings of the Conquest of Mallorca (1285-1290), which were in the porticoed gallery of the Berenguer de Aguilar Palace, became part of the collection of the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya (MNAC) after its refurbishment in 1961.

|

|

Picasso personally supervised the evolution of the works from France during all three years they took place. He received photographs and documents periodically to control the alterations of the different historical spaces designed for musealisation. His interest and implication in refurbishing what was to become the first monographic Picasso museum in the world are not usual and make it an exceptional case for the kind of collection it houses.

|

|

|

|

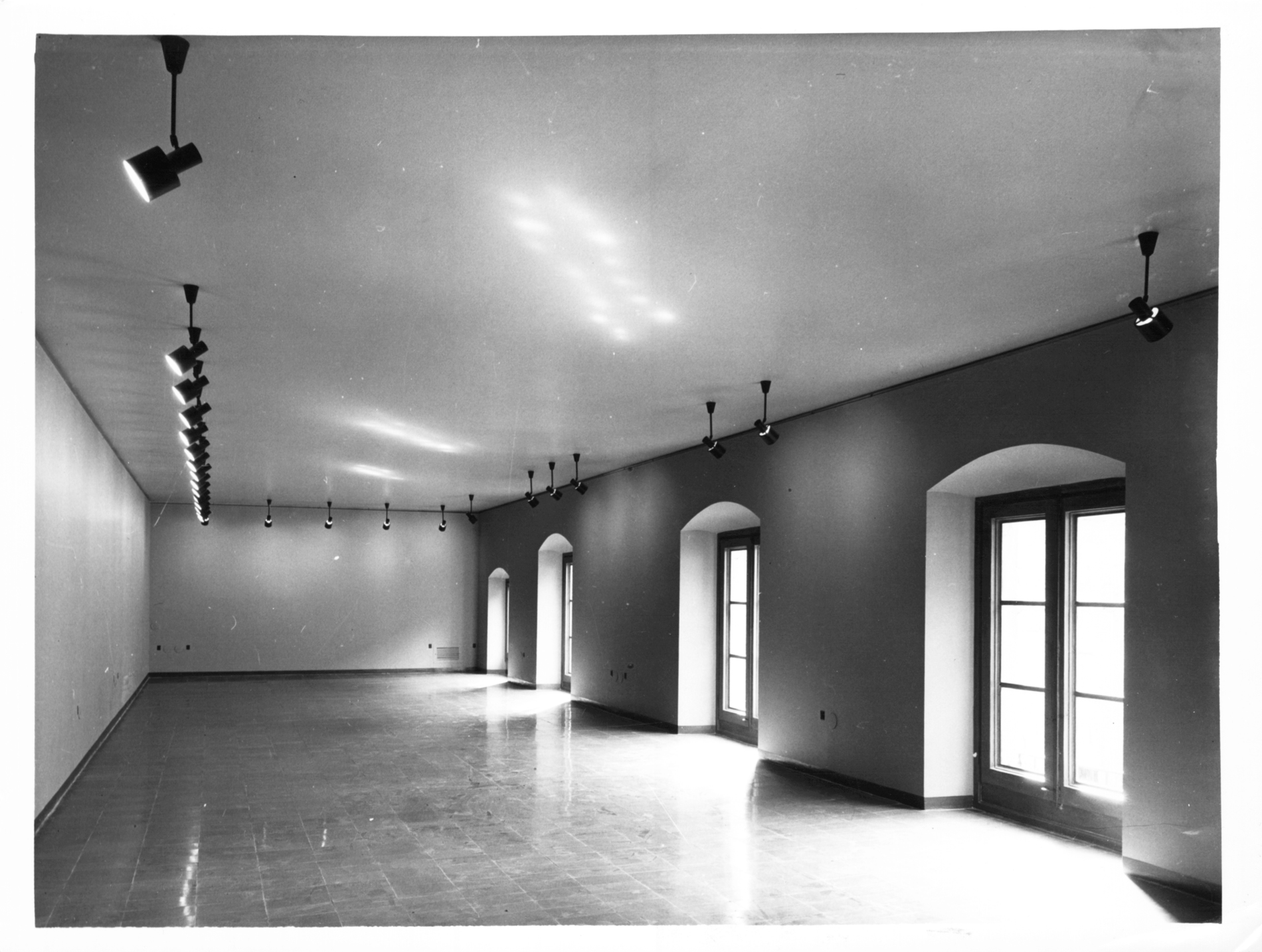

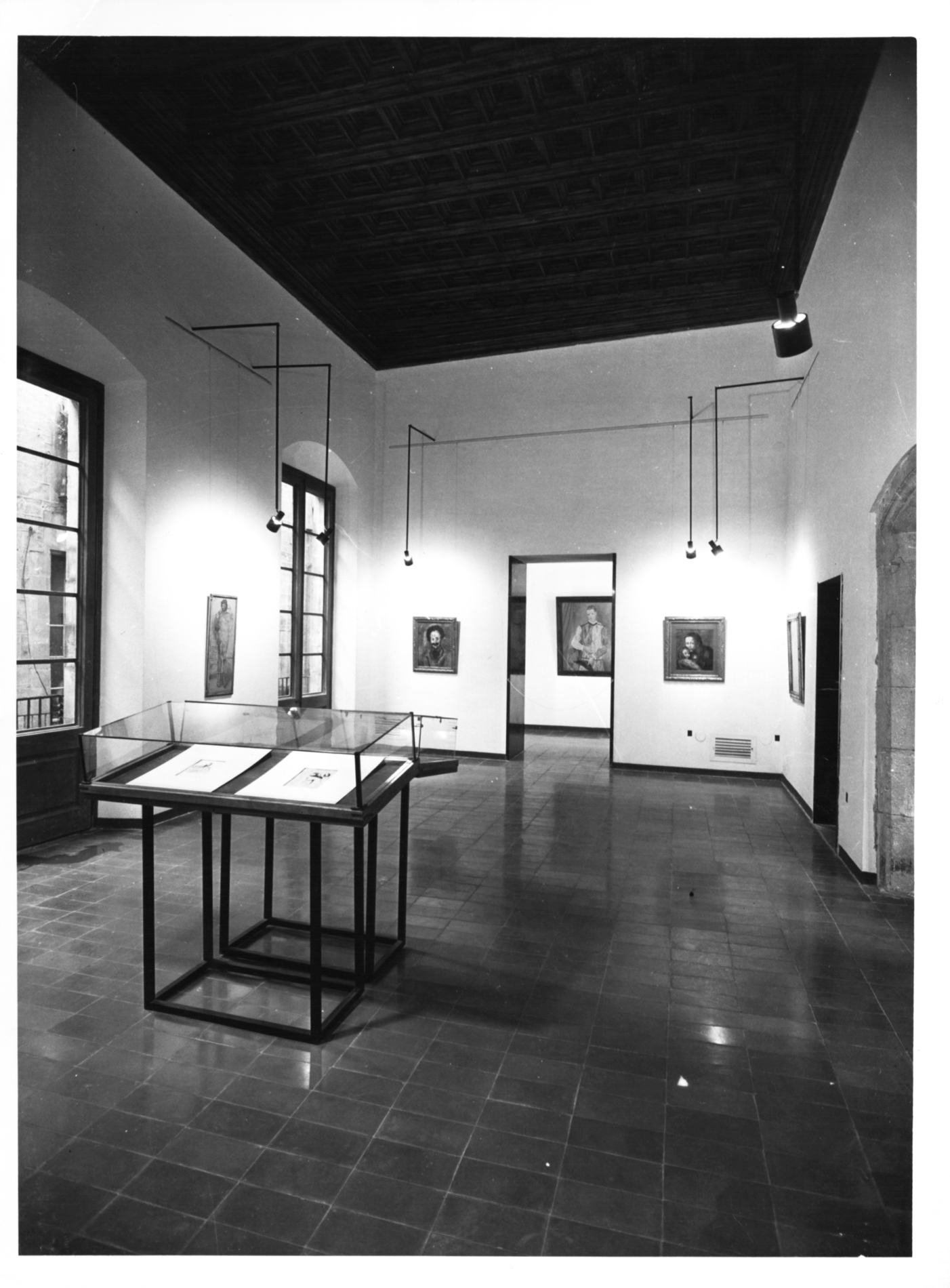

Once the remodelling was completed, the palace opened its doors to show to the public the works by Picasso from the private collection of Jaume Sabartés and those existing at the time in Barcelona's art museums. At that time, the museum route also included the palace's ground floor, whose climatic conditions and exhibition system are currently unsuitable for the preservation of the collection.

|

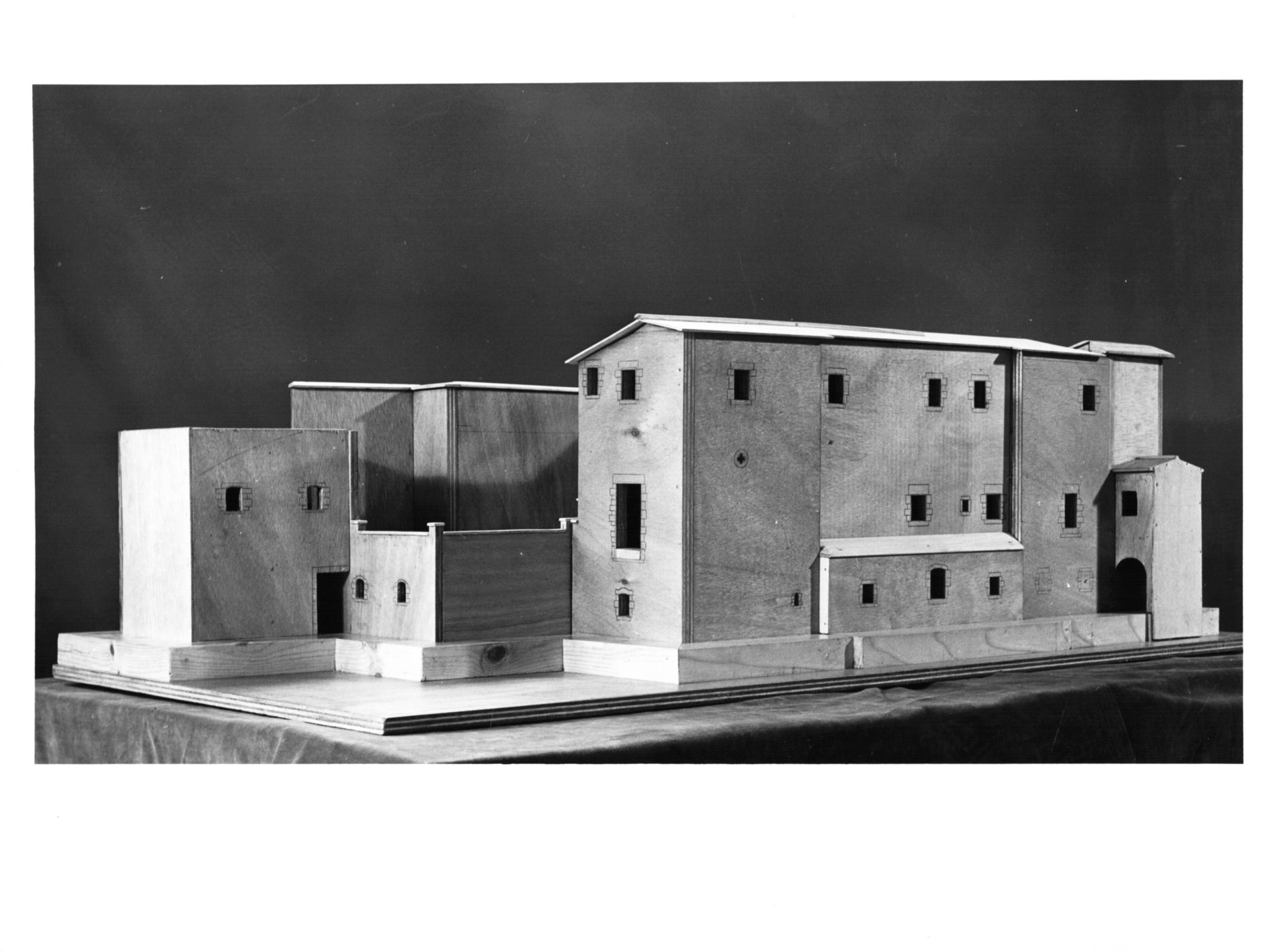

From its origins, the museum's appearance has changed its physical and museographic appearance. From one building, it has extended to the adjoining estates. It now occupies five, which today house the donations and acquisitions that have taken place over the years and which have required new museological and museographic approaches to adapt to the conservation of the works.

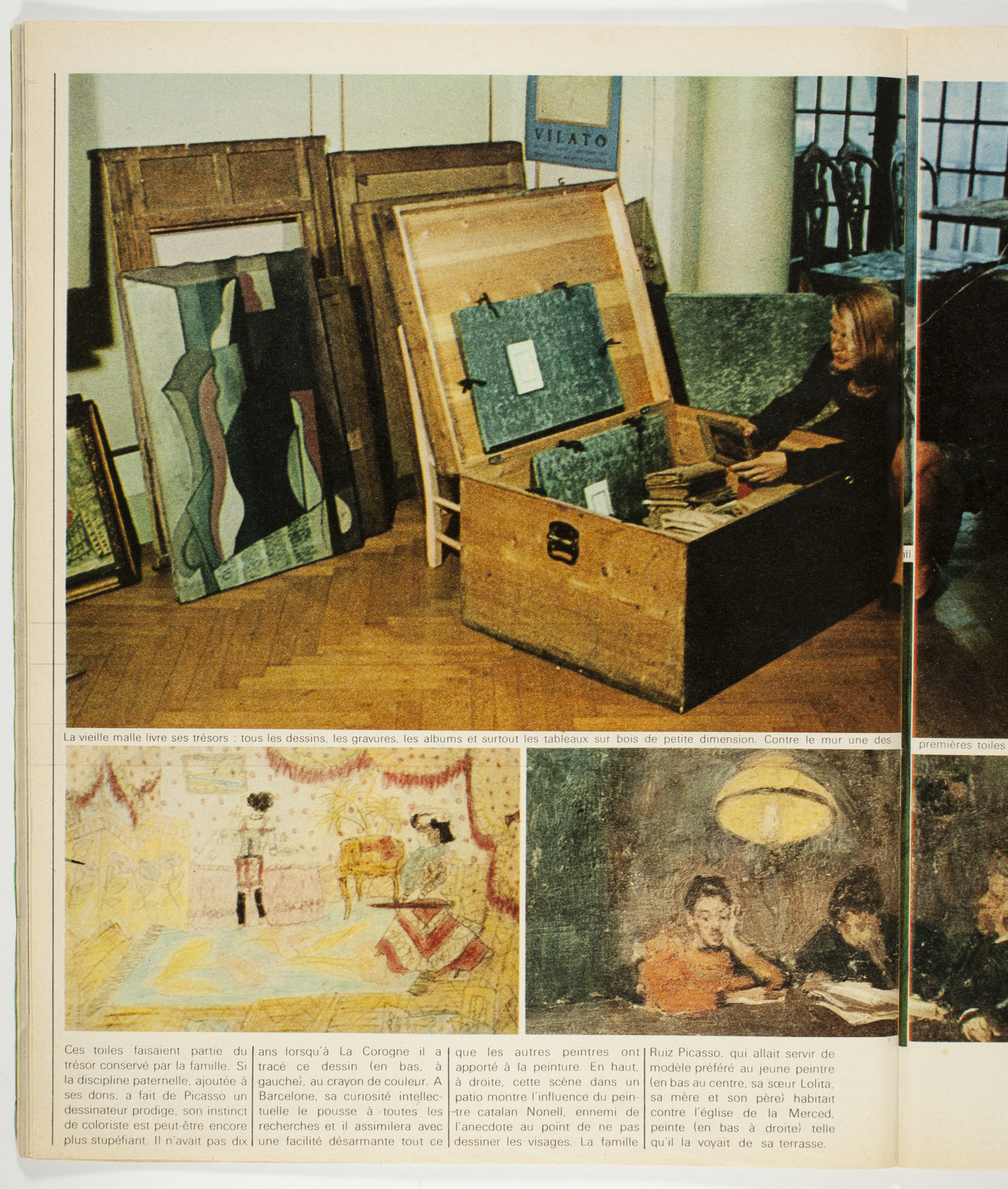

There were two critical moments in this process of expansion: on the one hand, Picasso's donation in 1968 of the 58 oils on canvas that make up the Las Meninas series; on the other, the artist's donation in 1970 of the works that the family had kept for three generations in the family home on Passeig de Gràcia: 236 paintings, 1,149 drawings, 17 notebooks, four textbooks with notes and drawings from his childhood, two engravings and 40 works by other artists that Picasso owned in his personal collection.

|

|

That same year, the Barcelona City Council promoted and financed the first extension of the museum with the annexation of the adjoining estate: the palace of the Baron of Castellet. On 18 December 1970, the new exhibition space was inaugurated, introducing the new collection. In 1978, work began on the project for the definitive expansion of the building we know today. The architect Jordi Garcés carried the commission out in different phases: in 1981, the Meca Palace was added; in 1999, the Casa Mauri and the Finestres Palace were fitted out as temporary exhibition spaces; and in 2011, the new building to house the Centre de Coneixement i Investigació (Knowledge and Research Centre) was built.

In 2003 and 2008, after a significant remodelling and adaptation of the exhibition rooms of the permanent collection, it was distributed in 22 rooms of very different sizes and characteristics. The permanent exhibit now runs transversally along the first floor of the four medieval palaces.

The collection's exceptionality and its location in a group of historic buildings are reflected in the museography. The remodelled open-plan, spacious and versatile spaces, intended for temporary exhibitions and designed according to current museographic criteria, can be adapted according to particular needs and can even use areas on the ground floor or even on the first floor of the building. By modifying the display system, the furniture, the lighting system and many other factors, the Museu preserves and guards its great legacy.

The Museum's permanent collection is unique: it allows us to observe Picasso's formative period and to recognise some of the artist's references, which will show in his later work. Moreover, it is essentially of organic origin, with a predominance of graphic works and supports such as canvas, wood and ceramics. Due to the nature of the materials, the control of the collection must be very rigorous and exhaustive to ensure the correct preservation of the collection.

Over the decades, preventive conservation has dramatically evolved. The building's structure and heritage characteristics have hindered essential issues such as air conditioning, which went from being individualised by room to centralised in the 1980s. Other factors causing degradation of the collections, such as lighting and museum equipment, have also been suitably updated thanks to the professionalisation of the preventive conservation sector.

The museum's preventive conservation and restoration team has an incomparable consultation tool in the photographic collections held in the Knowledge and Research Centre. These pictures have helped discover the collection’s past displays, the early equipment or exhibition systems. They have also served to evaluate and analyse management decisions of each period and the evolution of the collection's state of conservation today.

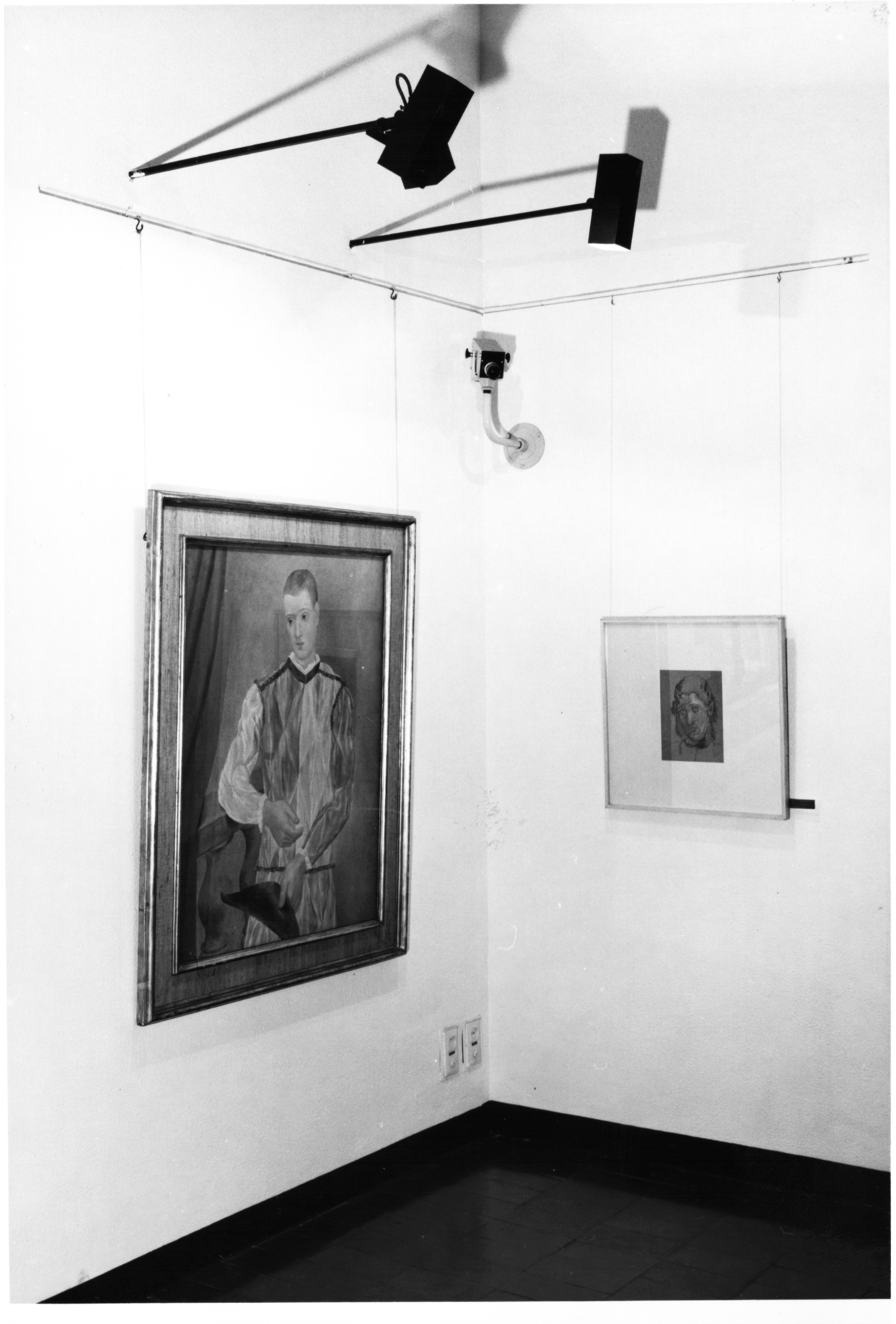

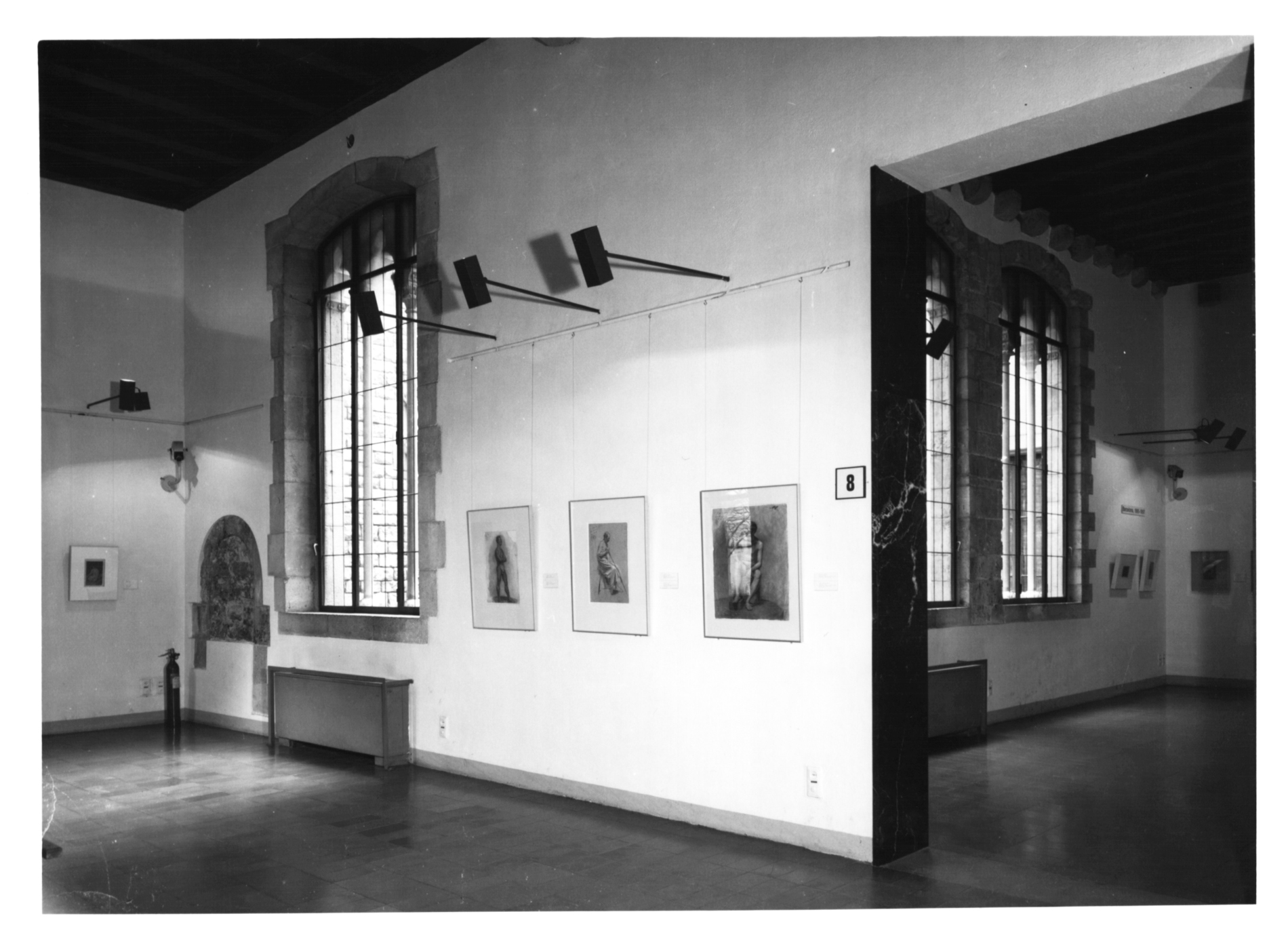

Thanks to this analysis, it has been possible to quantify the impact of one other agent, which, together with the climate, can most affect the collections: light. The incandescent lighting and fluorescent tubes of the 1970s gave way to dimmable halogen lamps in the 1990s; the spotlights in the current exhibition area are dimmed and filtered and are gradually being replaced by LED technology light sources.

|

|

The incidence of natural light can also be destructive. Initially, and for years, the works were exhibited next to the large windows of the building, unprotected. Some documentary sources express concern and advise placing curtains or shutters to control and avoid its effects. Currently, many of the openings in these buildings are walled up or present filters on the glass or reinforced protection with blinds.

|

|

The photographs also made it possible to analyse the systems used to show the collection and see how the display cases and parameters were adapted to the architecture of the building. It is interesting and somewhat alarming to observe how in some areas, walls were fitted with wooden panels to hang the works, while in others, glass and iron showcases were used to display, at the same time and indiscriminately, pieces of different nature, illuminated by fluorescent lights without caring about the various degrees of photosensitivity. The photographs even show potted plants in some of the exhibition rooms. To a greater or lesser degree, these decisions have influenced the preservation of the collection.

|

In the archive images, we can also discern the labyrinthine route between rooms of irregular dimensions that the Museu initially had, the scarce control of public access, and the absence of security systems. In addition, we can recognise areas currently considered unsuitable for the collection exhibition due to their climatic conditions.

|

|

|

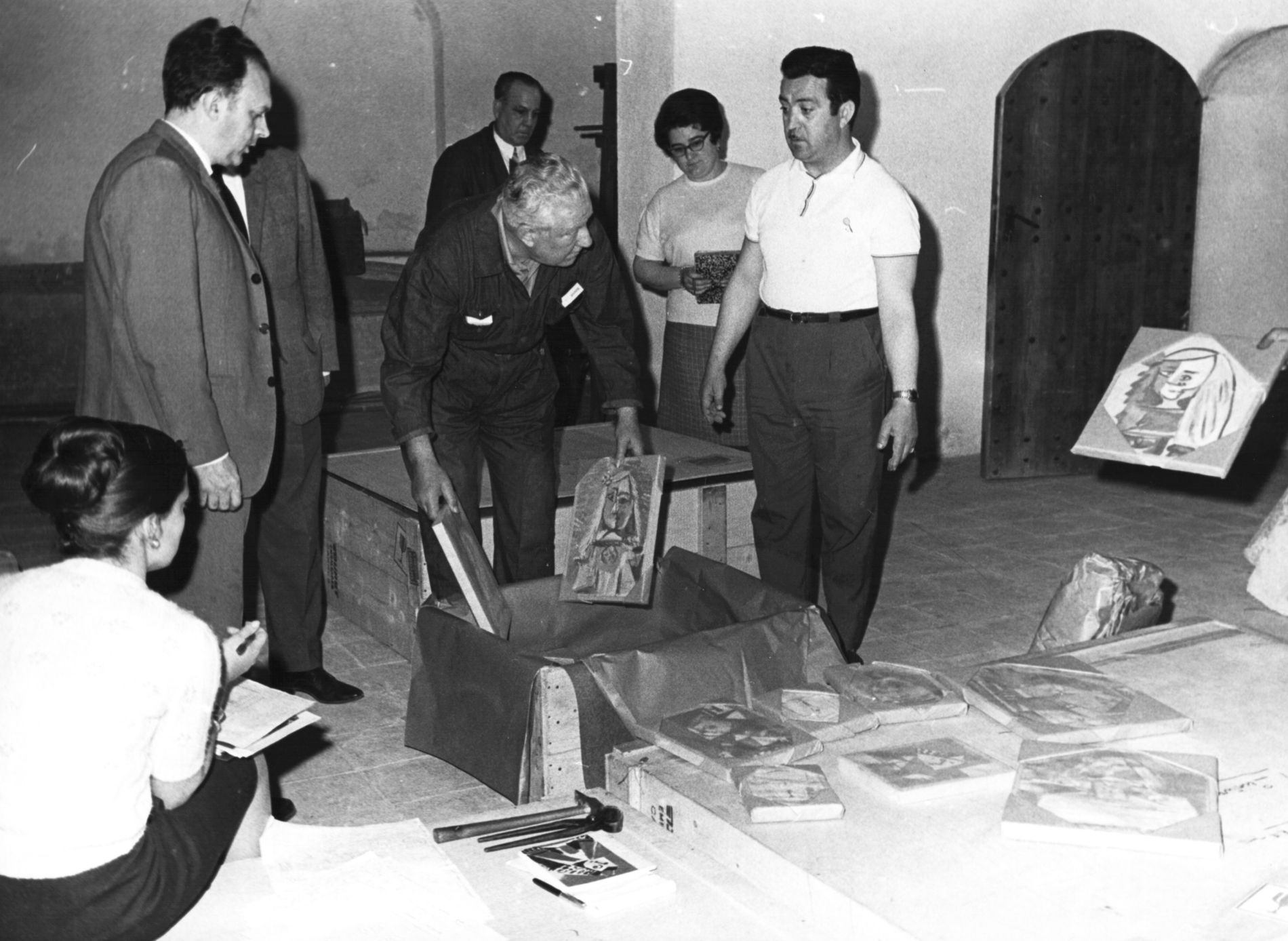

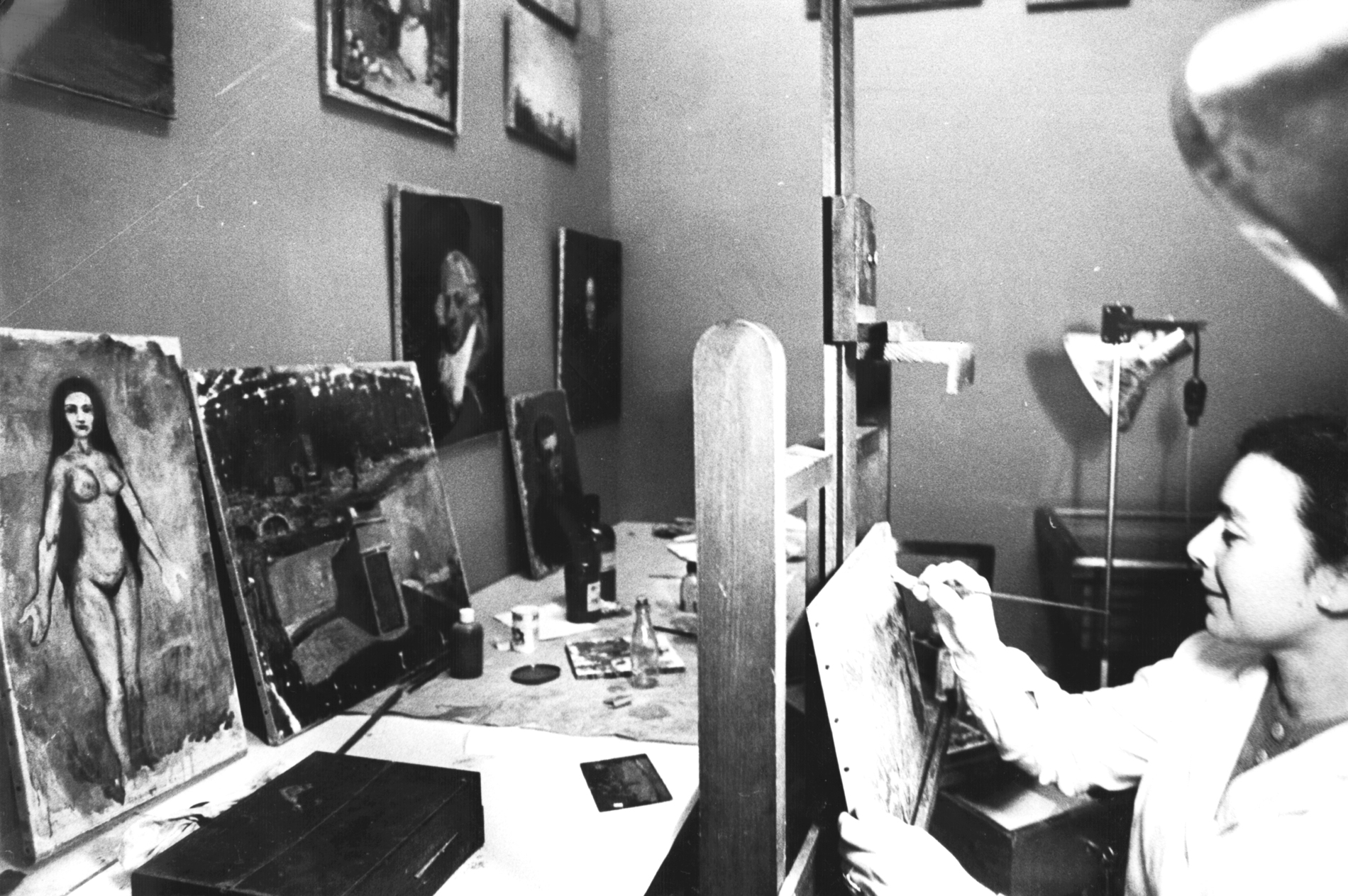

Francesc Mèlich's collection is invaluable for assessing the current state of the works. In 1959, at the express wish of Picasso himself, Melich photographed all the works in his sister Lola's house in Barcelona. Nine hundred ninety-four black and white photographs were sent to the artist, which he used to select the works he would donate to the Museum in 1970. This became what can be considered the collection's first cataloguing work and a vital point of reference for understanding the restoration work that was subsequently carried out.

|

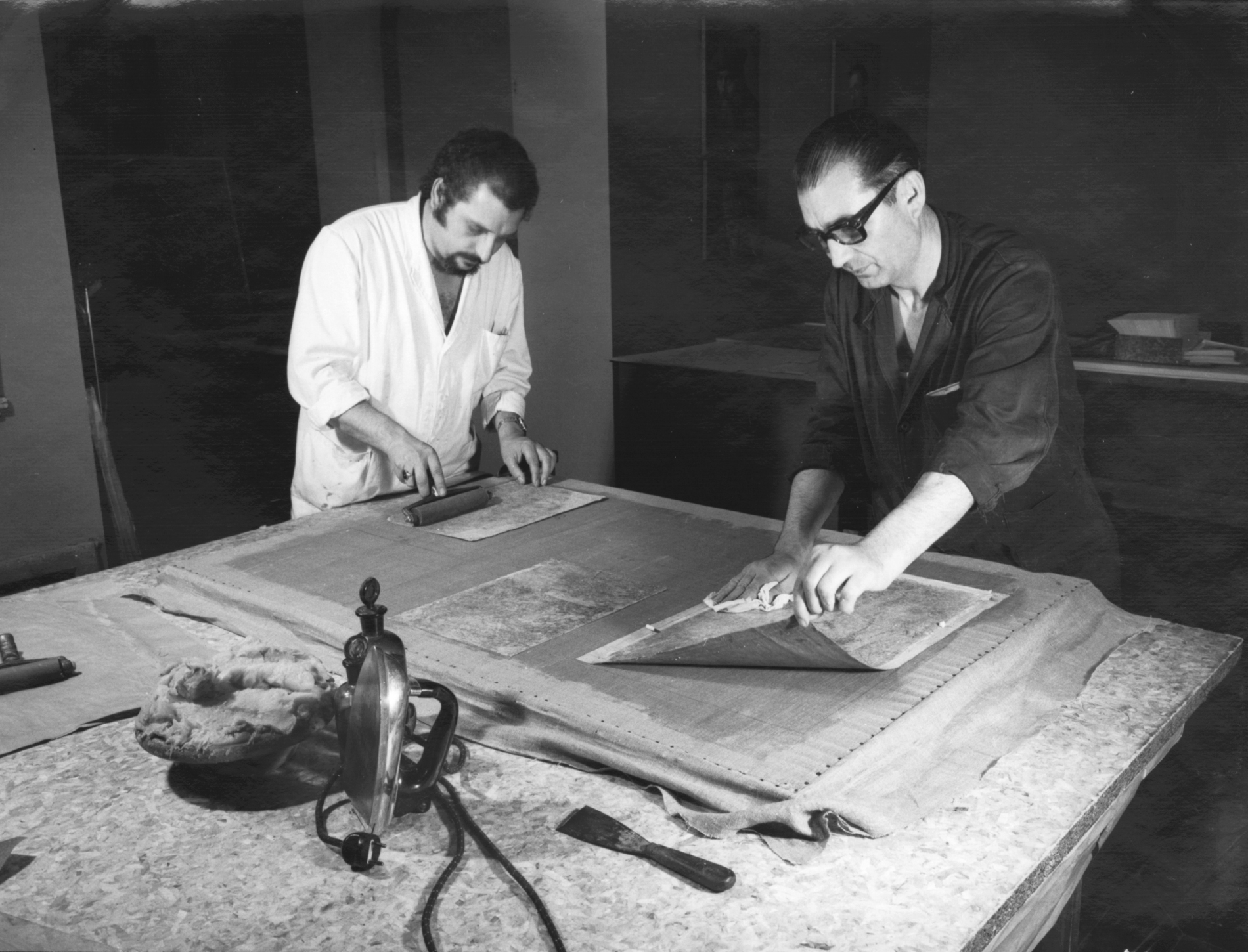

Following the act of donation, the City Council received the works on 8 May 1970 and sent them to the restoration workshops of the Museu d'Art de Catalunya to be restored and exhibited at the Museu Picasso from 18 December of the same year. The rush and lack of time prevented a slow reflection on the overall state of the collection and the corresponding individualised proposal for each work; intervening on practically all the works donated in such a short space of time resulted in restorations that were not very personalised.

|

|

The Francesc Mèlich collection's revision provides a great deal of information on what the collection was initially like, accurately recording the specific locations of some of the most emblematic works and helping us assess their current state of conservation.

|

|

In recent years, through interdisciplinary work teams, the Museum has promoted the scientific study of the works, using preferably non-invasive analysis techniques to study the materials and methods used by Picasso in depth. These studies subject the pieces to different ranges of light in the electromagnetic spectrum for a multispectral reading that allows us to approach the creative processes of the brilliant Picasso.