Picasso Ceramics. Jacqueline's Gift to Barcelona

This exhibition commemorates the thirtieth anniversary of the donation that Jacqueline Picasso made to the city of Barcelona of forty-one unique ceramic works, the dishes, jars and bowls that Picasso had given to his wife over the course of the two decades during which they lived together.

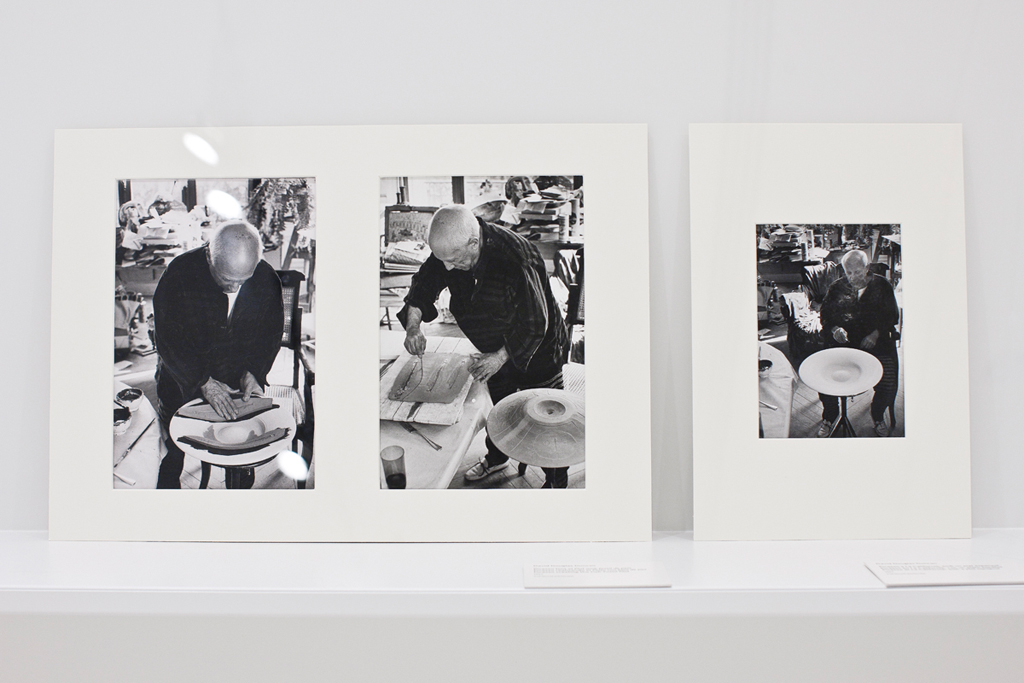

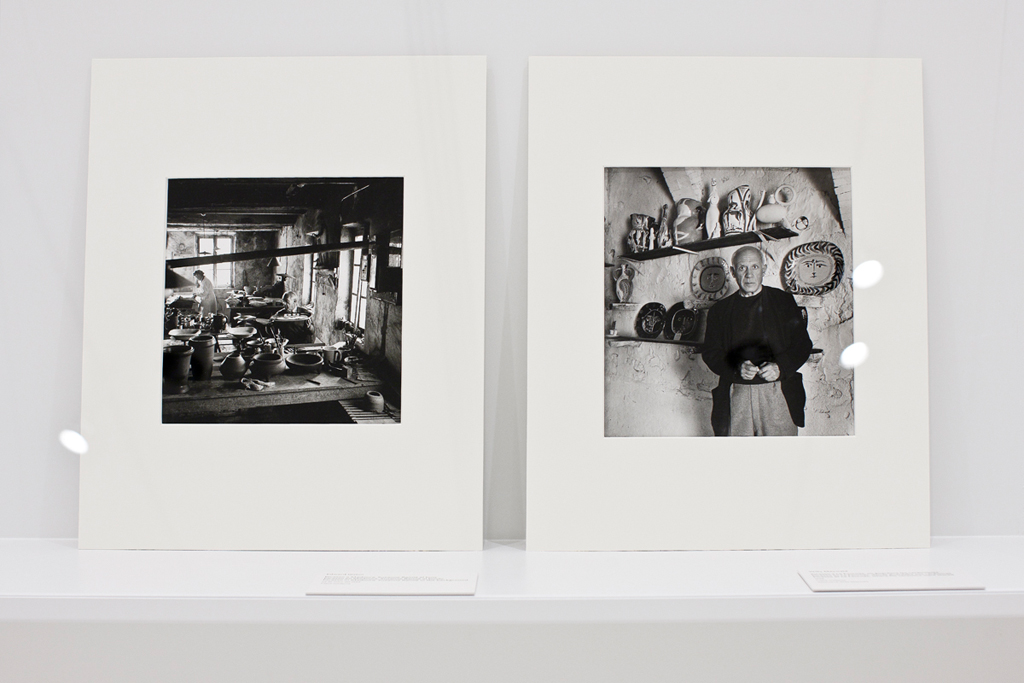

In 1947 Picasso began to frequent the Madoura ceramic workshop in Vallauris, invited by its founders Suzanne and Georges Ramié. He particularly liked the challenge of working with three-dimensional objects and the possibilities these offered: a hand-painted engraved dish could become a head; a group of women or ballerinas could surround the body of a jar ad infinitum; the concave interior of a bowl could create the illusion of volume in the figure it depicted. Such works reveal Picasso's taste for the popular forms and decorative techniques he used in his experiments to transform everyday objects into art works.

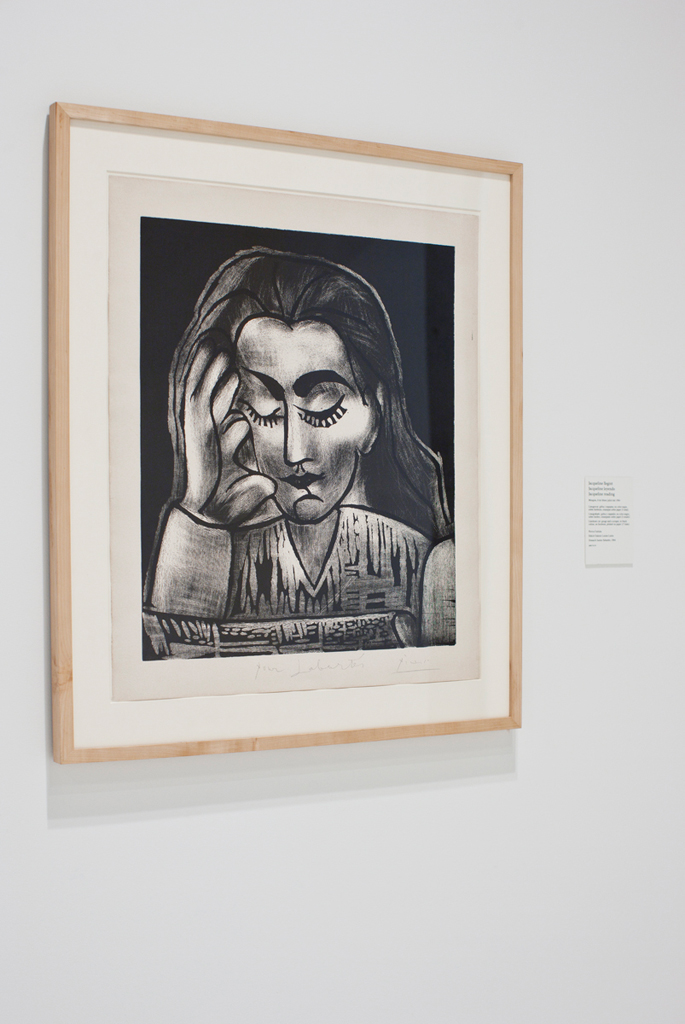

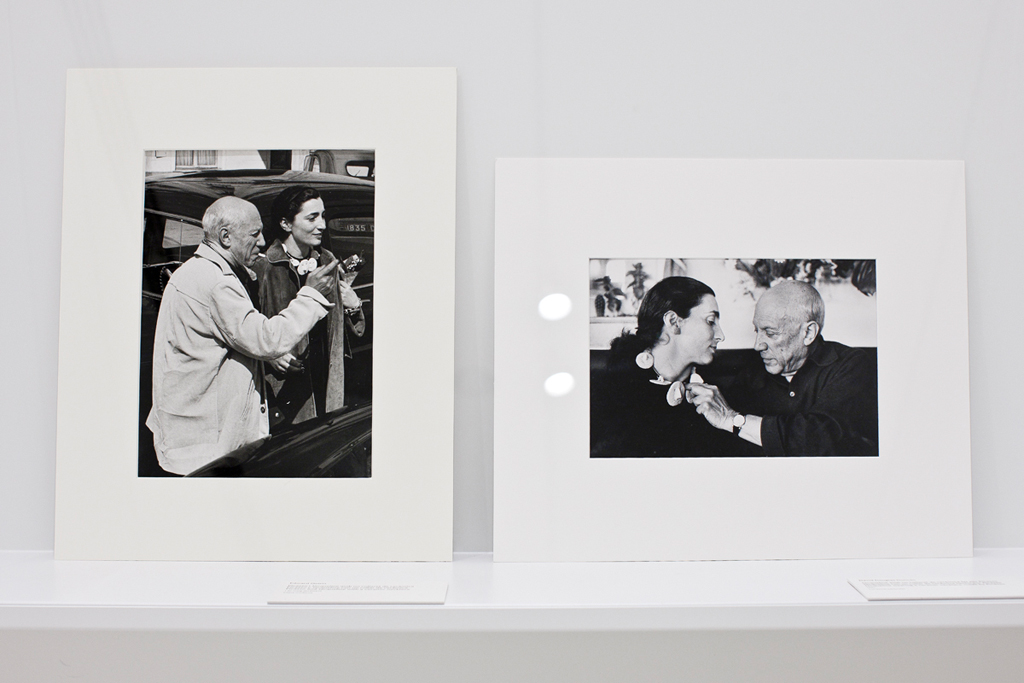

Jacqueline Roque and Picasso met in 1952, shortly after she started working in the gift shop at the Madoura studio. Jacqueline soon became his muse, his wife and companion, and the couple lived together until Picasso's death in 1973. At the opening of a great exhibition of Picasso's ceramics held in Barcelona in 1982, for which Jacqueline had loaned forty-one unique pieces from her collection, she made the surprising announcement that she intended to donate the works in question to the city.

Early experiments at Madoura

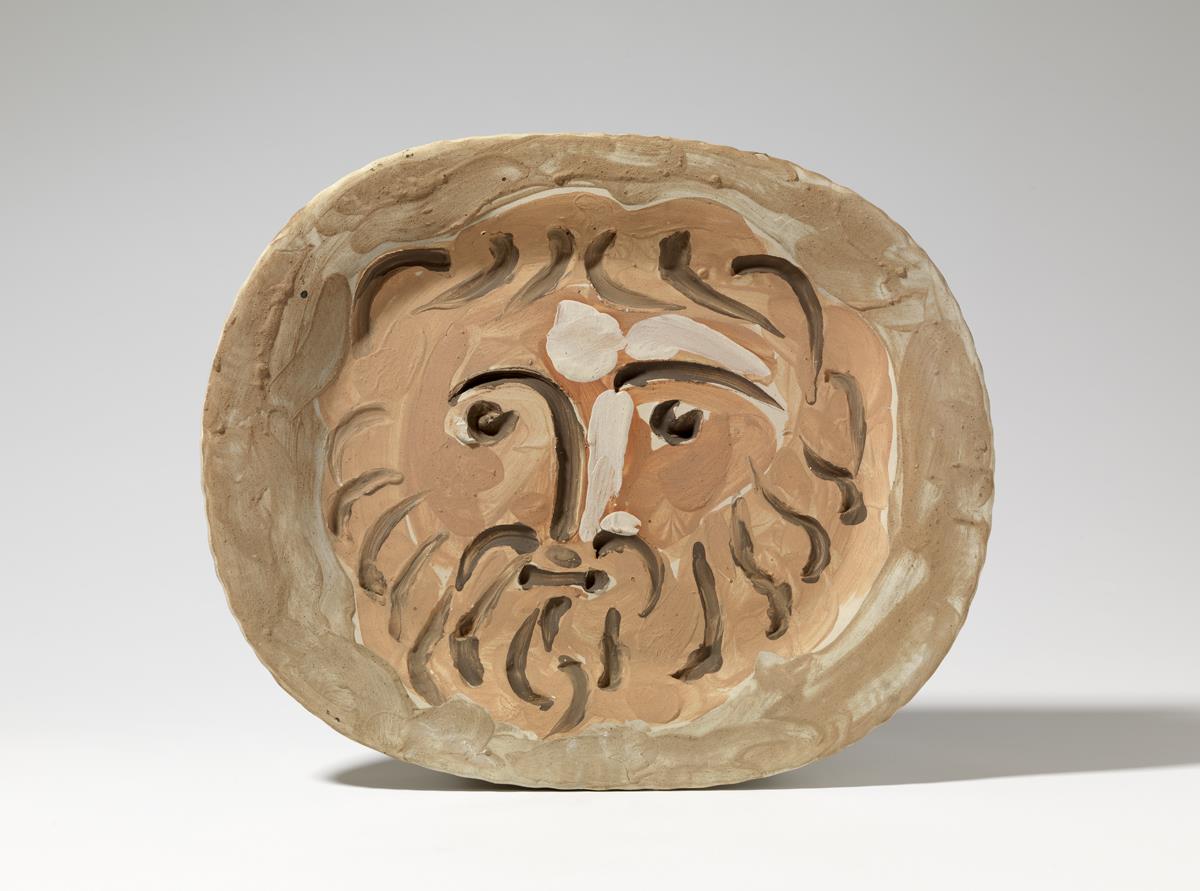

The large press-moulded plats longs that were regularly produced at Madoura provided Picasso with a ready format to realise his experiments, which he carried out at remarkable speed. In terms of techniques of pottery decoration, he quickly mastered his knowledge of ceramic materials. Painting with a 'blind palette' – that is, with colours that do not reveal themselves until fired in a kiln – Picasso either drew on traditional patterns and combinations or created his own sometimes improbable (from a technical point of view) inventions. For subject matter, Picasso drew on traditional imagery, including fruits or fish in the sea, but he also populated the surfaces of his plats longs with figures and mythological scenes. The shape of the plate has an inherent analogy with a head (whether oriented vertically or horizontally), and Picasso turned many of them into heads of women or fauns.

Traditional forms

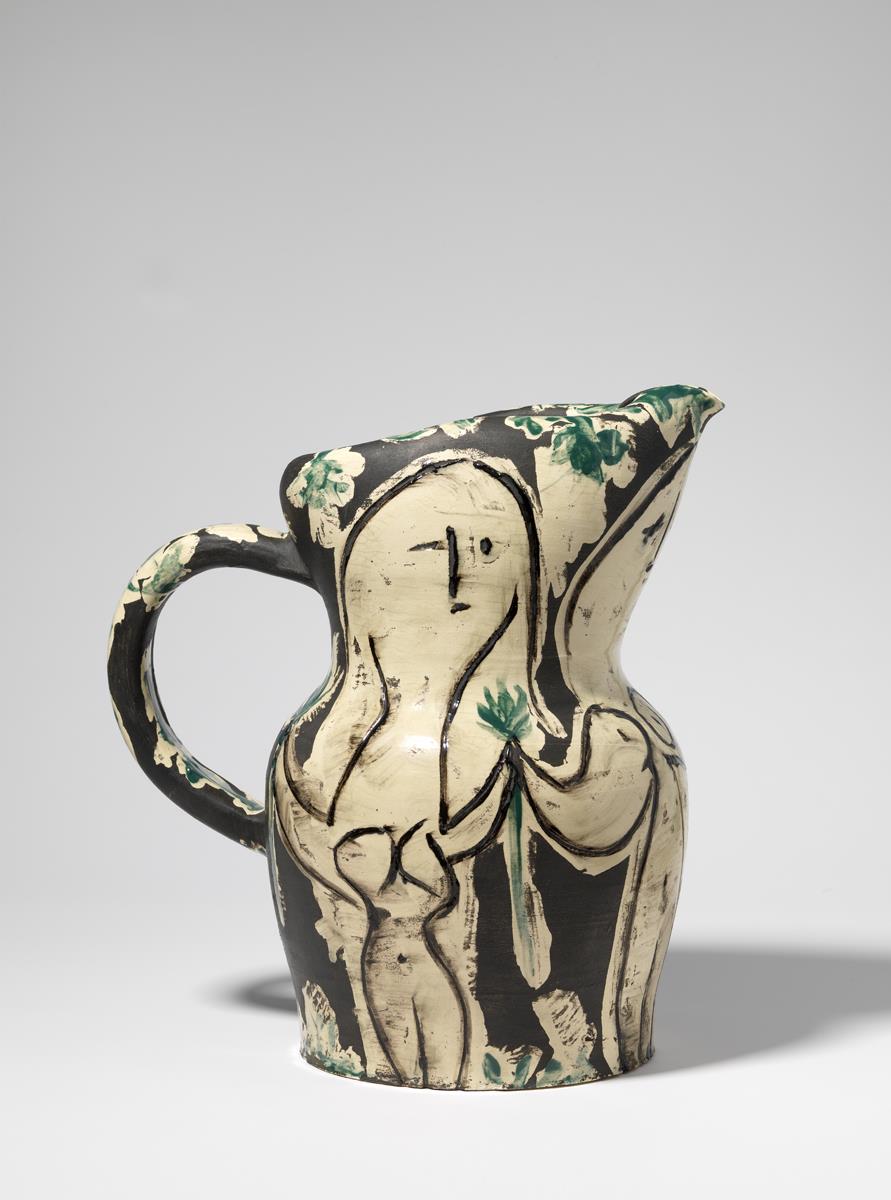

The shape of the large pot known as a 'gothic pitcher' was created by Suzanne Ramié, who based her design on traditional jugs with a spout and a single handle. At Madoura such pitchers were thrown and produced in series by the craftsmen, generally on a large scale, though the sizes varied. Picasso saw in the form of the gothic pitcher a ready analogy for the bodies of women, and many of his decorations feature nudes on all sides of the vessel. In some cases, he transformed the whole of the form into a head, with the modelled upper rim suggesting hair.

Pignates

During the months of August and September 1950, Picasso was preoccupied with producing his own evocations of ancient pottery, which he carried out on locally manufactured pignates. These grogged, pink earthenware vessels had been made in Vallauris for centuries. When Picasso first lived and worked there, a few factories still produced the typical straight- or curved-sided cooking vessels. The decoration imitated the limited palette of the Greek and Etruscan vase artists, using only black with white or red slips. The locally dug clay used for the pignates was not finely ground and it often contains particles of calcareous material. Because the vessels were glazed only on the interior and the exterior remained porous, any moisture may cause the chalky particles to swell, forcing chips of the surface to 'pop out'. This makes these decorated pots particularly fragile, although Picasso is not likely to have been bothered by the unpredictable damage.

Empreintes originales

In the spring of 1955, just weeks before Picasso and Jacqueline moved into La Californie in Cannes, the artist worked at Madoura on a number of empreintes originales. The idea to come up with a ceramic process that had parallels with printmaking was Picasso's. He and Jean Ramié (son of Georges Ramié) worked together to produce plaster moulds from plain ceramic objects. The artist carved these matrices, from which clay impressions could then be taken. Each empreinte (print) would thus faithfully reproduce the artist's original design, with the lines carved into the plaster appearing in relief above the surface of the pottery. Later, in order to achieve recessions in the clay empreintes, Picasso also dripped liquid plaster onto the moulds. In most cases Picasso dated the moulds on the border of the piece, although he usually incised the numbers the way that he saw them, so that they appear in reverse on the clay impressions.

Work at La Californie

After Picasso moved with Jacqueline to La Californie his practice in ceramics changed. At that point, he set up space in the villa for his activity in pottery. In some respects, the complexities of his inventions in techniques and materials, which had characterised his work in Vallauris, gave way to simplified means. Painting primarily with slips and oxides and using carving or incising techniques, Picasso produced designs that once again echo the traditions of the ancient pottery painter. In terms of the forms themselves, he generally worked on Madoura jugs and plates, which were delivered to him from the pottery, or he ordered commercially produced floor and ceiling tiles for decoration. The decoration of many of these pieces returns again and again to the theme of the bullfight, which also appears in other media during this period.

Plats espagnols

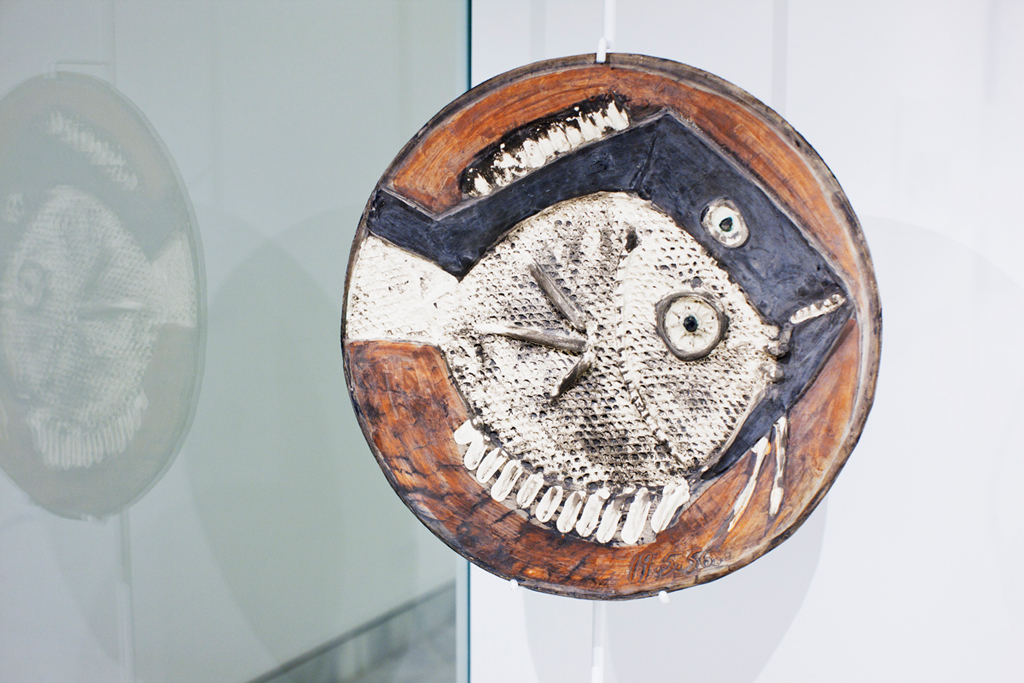

In 1957 Picasso and Jacqueline were invited as honorary guests to attend the opening of the great exhibition of some 600 Spanish ceramics at the Palais Miramar in Cannes. The show, "La céramique espagnole du XIIIe siècle à nos jours", included some of the most celebrated examples of medieval and later ceramics from different regions of Spain. Picasso's response to what he saw was almost immediate; he commissioned from Madoura a series of what he called plats espagnols, large platters with upraised centres. Not only was he enchanted with the scale and format of the plats espagnols, he was also stimulated by the manner in which the medieval examples were traditionally decorated, with fish and other animals occupying the centres, and garlands or other motifs encircling them around the wide borders, as if the ceramic were a heraldic shield.

Work of the 1960's

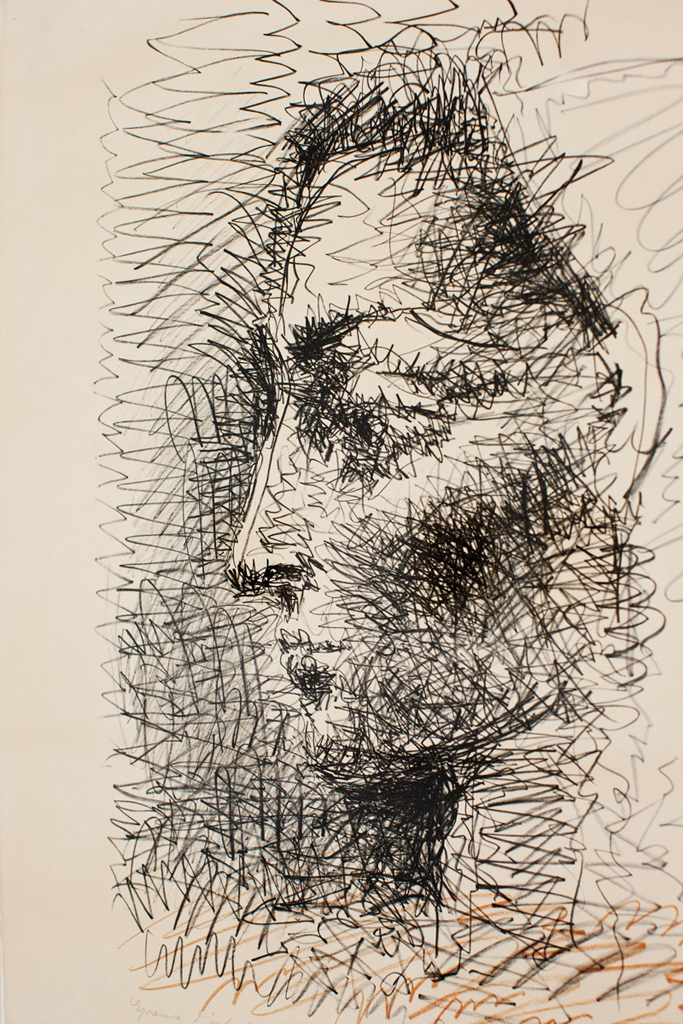

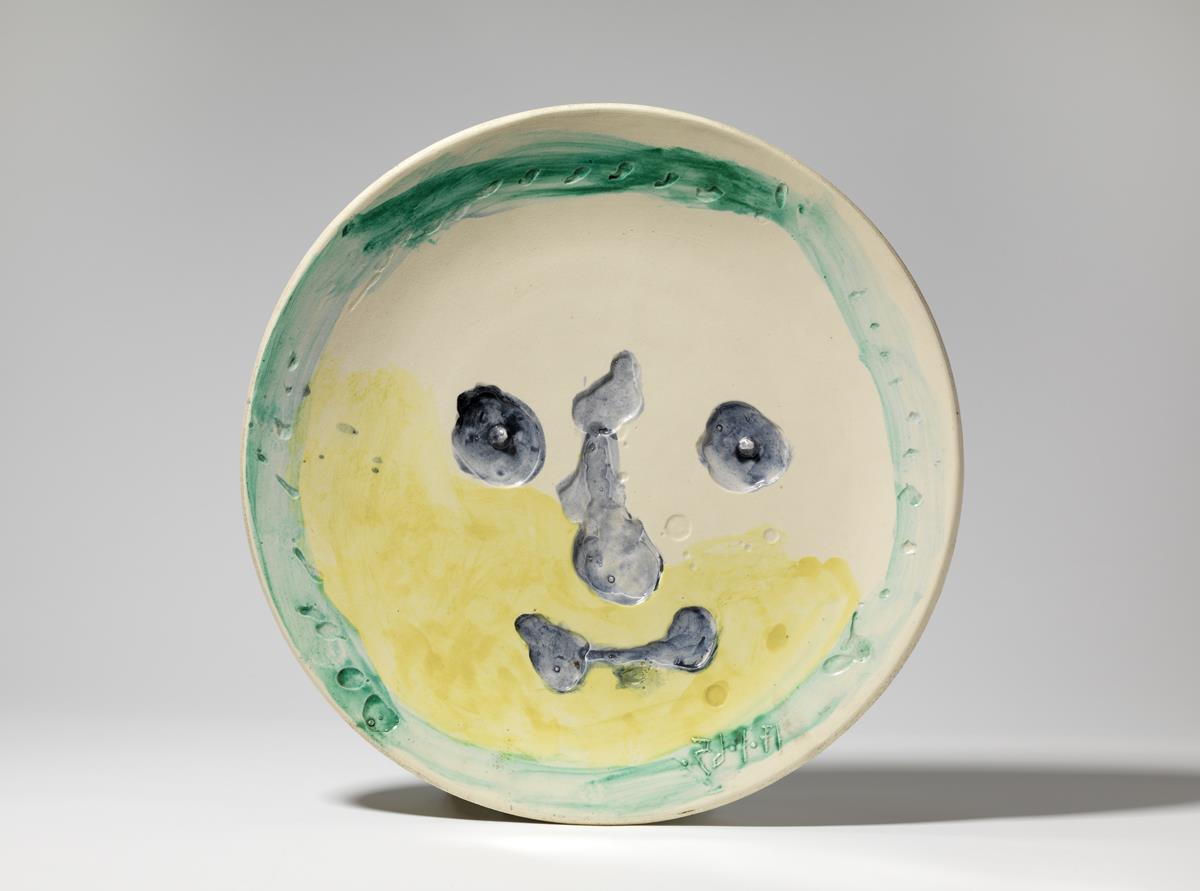

During the 1960s, Picasso resumed his habit of working at the Madoura pottery, and he tried out new variations on the empreintes originales as well as the decoration of large bowls, tiles and a few other shapes, often selecting those from the ceramics being produced in editions. In these cases, he decorated examples for his own pleasure rather than simply supplying models for the craftsmen to replicate. In a number of round plates rendered as heads the processes he used suggest the pitting and ravages of time and old age in the faces that hauntingly look out at us. This aspect of Picasso's late work can also be discovered in the paintings and drawings of the last decade of his life.