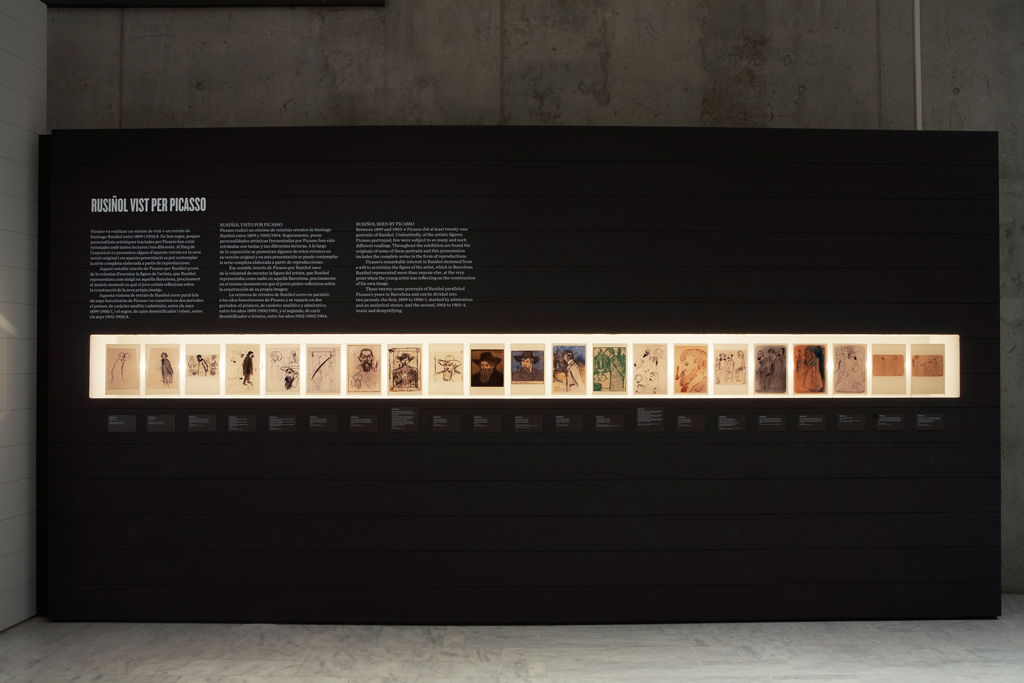

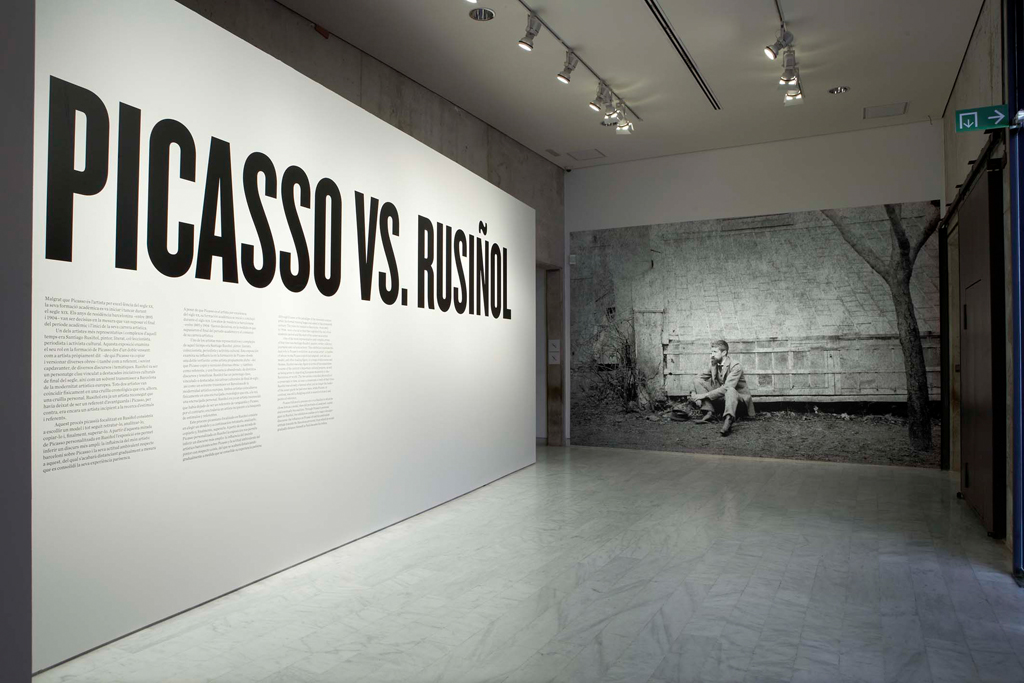

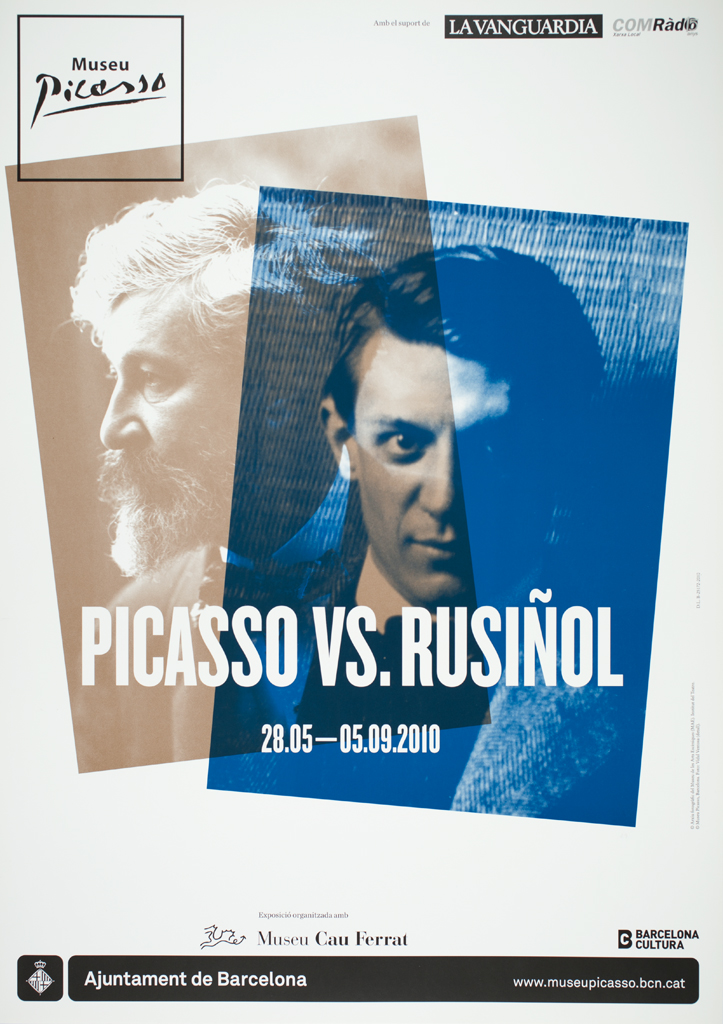

Picasso vs. Rusiñol

Picasso vs. Rusiñol explores the various connections between the two artists and also enables us to infer the influence of Rusiñol and of Barcelona's artistic milieu on Picasso, an influence the Spanish artist would gradually shake off as his Parisian experience was consolidated.

The years in which he lived in Barcelona, from 1895 to 1904, proved decisive for Picasso insofar as they marked the end of his academic training and the beginning of his career as an artist. The painter, man of letters, collector, journalist and cultural activist Santiago Rusiñol was one of the most complex and representative artists of the period, and Picasso took him as a model: he portrayed him, analysed him, copied him and eventually surpassed him.

For the first time, Picasso's regard for Rusiñol is revealed. The connection enables us to trace the influence that the Barcelona art world had on Picasso, and how he responded ambivalently to that influence, gradually distancing himself from it as his Parisian experience proved increasingly significant.

The Shared Place: Barcelona

Although in this period both were absent from the city for extended periods, it was in Barcelona that Rusiñol and Picasso coincided. Picasso was born in Malaga in 1881 and Rusiñol in Barcelona twenty years earlier, in 1861. When he arrived in Barcelona, Picasso was still a teenager and Rusiñol was a widely recognized artist and had made several trips to Paris. In his first years in Barcelona, Picasso alternated his studies at the Llotja School of Fine Arts with his own, less inhibited work, with his family and the city of Barcelona as his main subjects. His early work evidences an undeniable tension between formal training and his subversive tendencies, as is clear in a range of works and documents. This duality persisted for several years, during which he showed works at several official exhibitions. The first took place just seven months after Picasso arrived in Barcelona, when, at the age of fourteen, he showed The First Communion at the Third Exhibition of Fine Arts and Artistic Industries in Barcelona in 1896. In this debut in society, Picasso's works hung alongside those of some of the most important artists of the time, among them Santiago Rusiñol, one of whose works from the exhibition Picasso adapted.

Modernisme and Anti-Modernisme

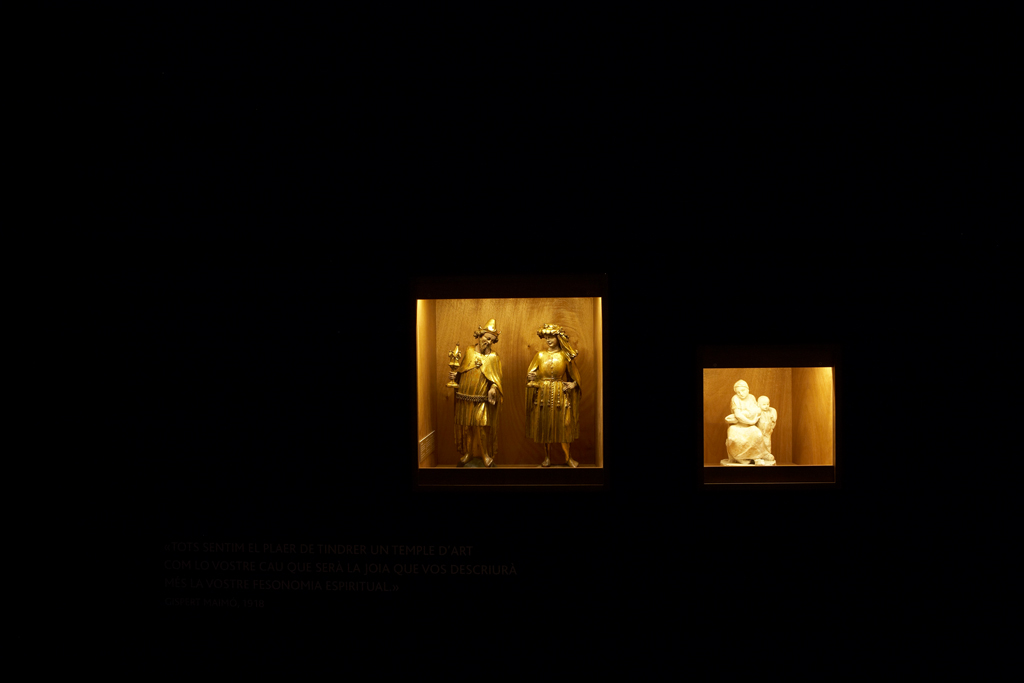

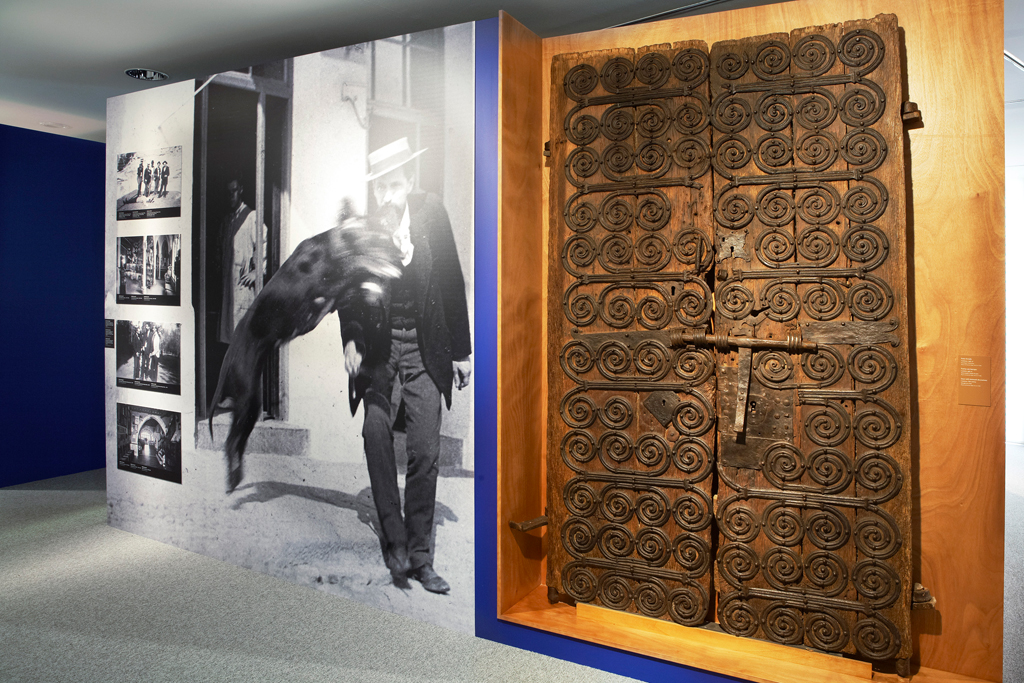

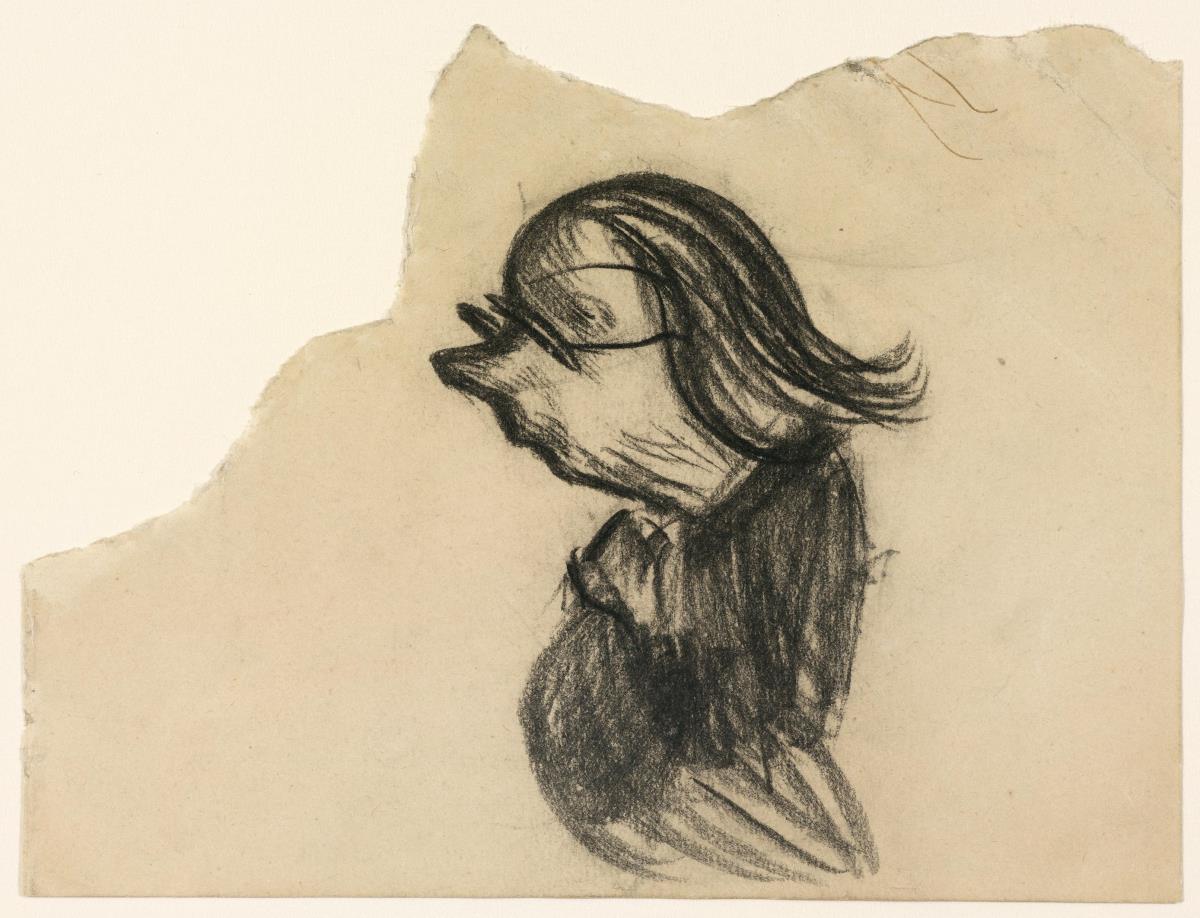

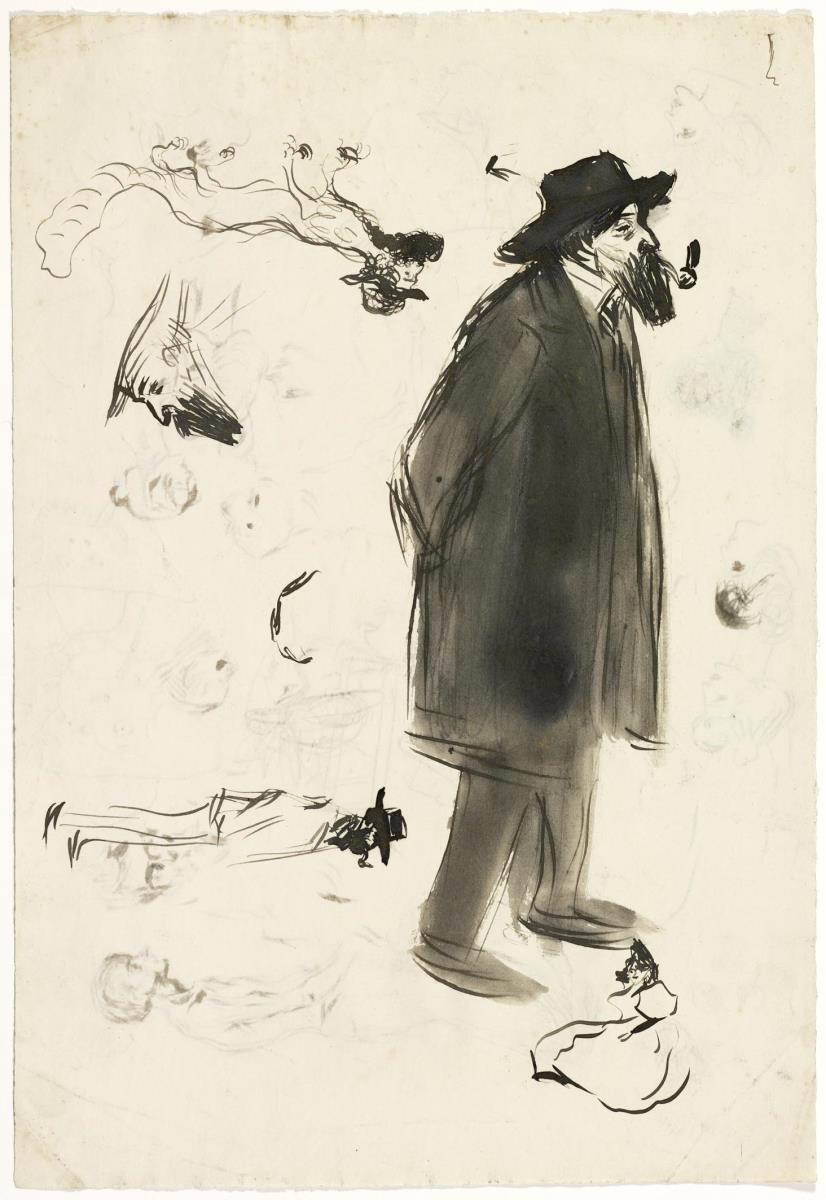

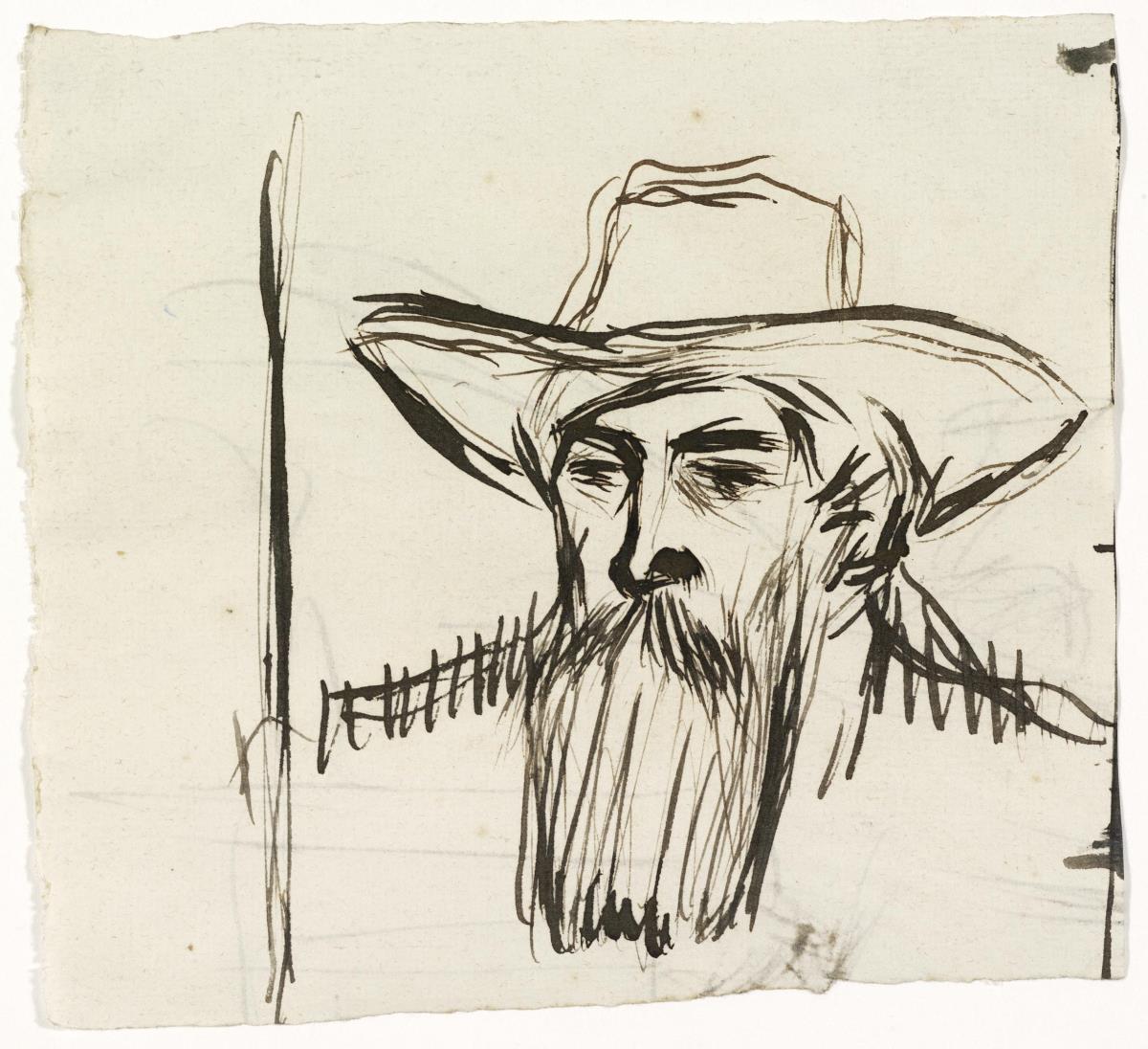

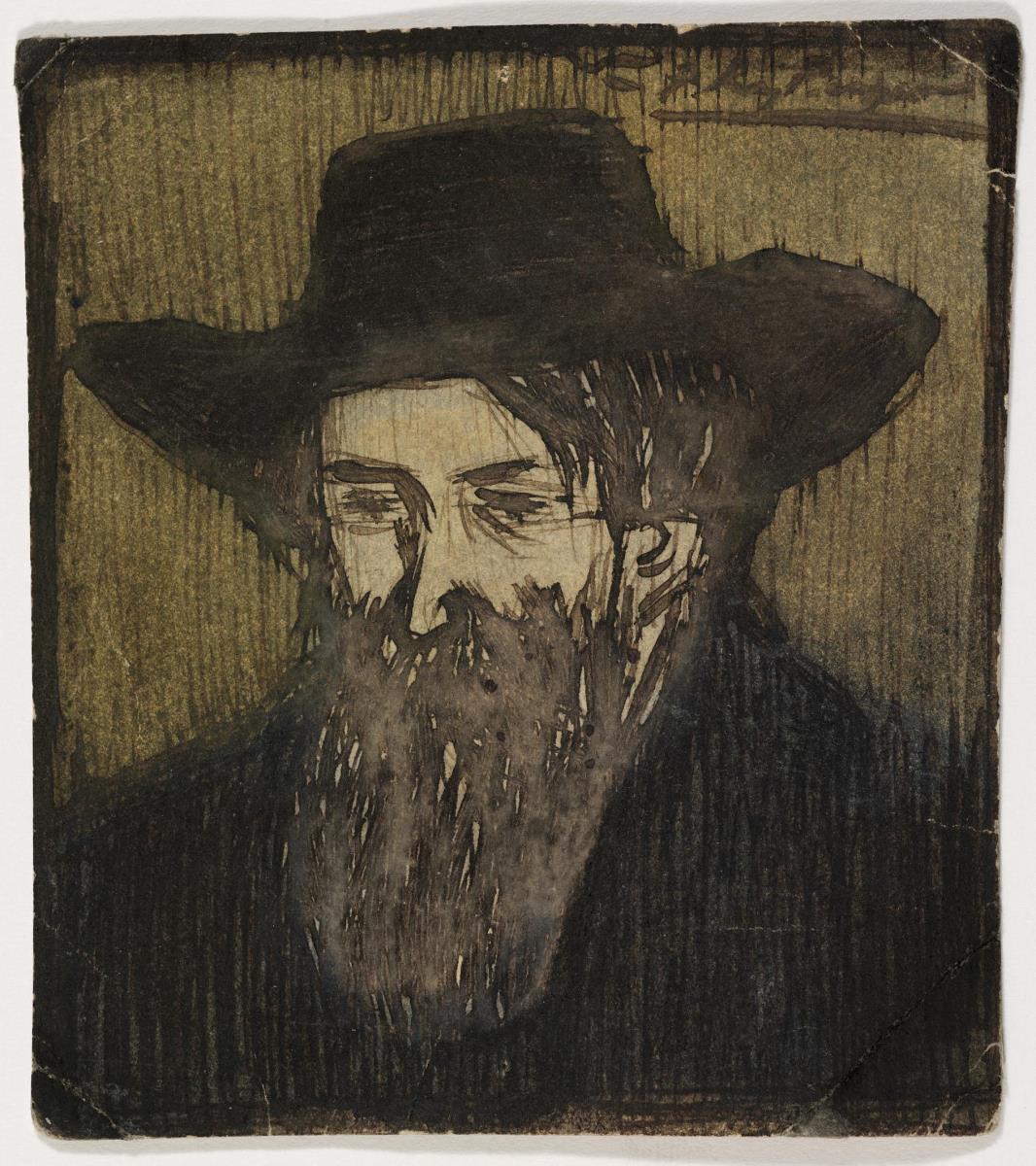

Santiago Rusiñol was certainly the leading figure in the Barcelona art scene and he had been at the forefront of some of the most important cultural projects of the late nineteenth century, including his museum-home Cau Ferrat and the Modernista festivals in Sitges, and the tavern Els Quatre Gats. It was probably around 1899 that the personal relationship between the two artists began, who then belonged to very different social and artistic orders. That was the year of Picasso's first portraits of Rusiñol, some possibly done even before they had struck up a personal acquaintance, and although they were never very close Rusiñol did become one of the first collectors of Picasso's work. Picasso's relationship with the Modernista movement was ambivalent; he borrowed from its themes and discourses, but also criticized it when it interested him to do so. This critical stance took two forms: first, through contact with the younger generation which was searching for new ideas beyond the aesthetics of the first Modernista generation led by Rusiñol, and, second, in a series of works satirizing the Modernistas.

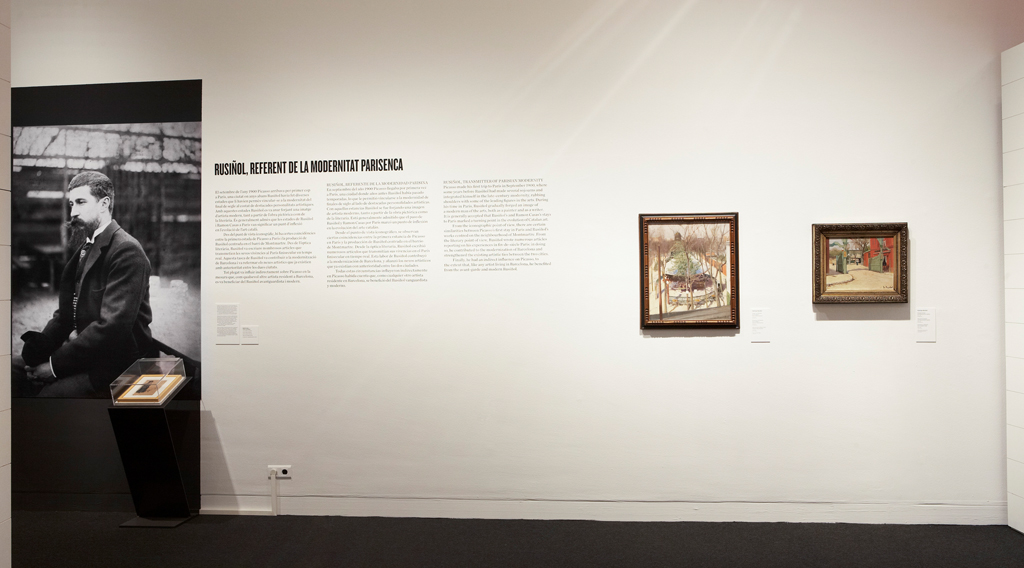

Rusiñol, transmitter of Parisian Modernity

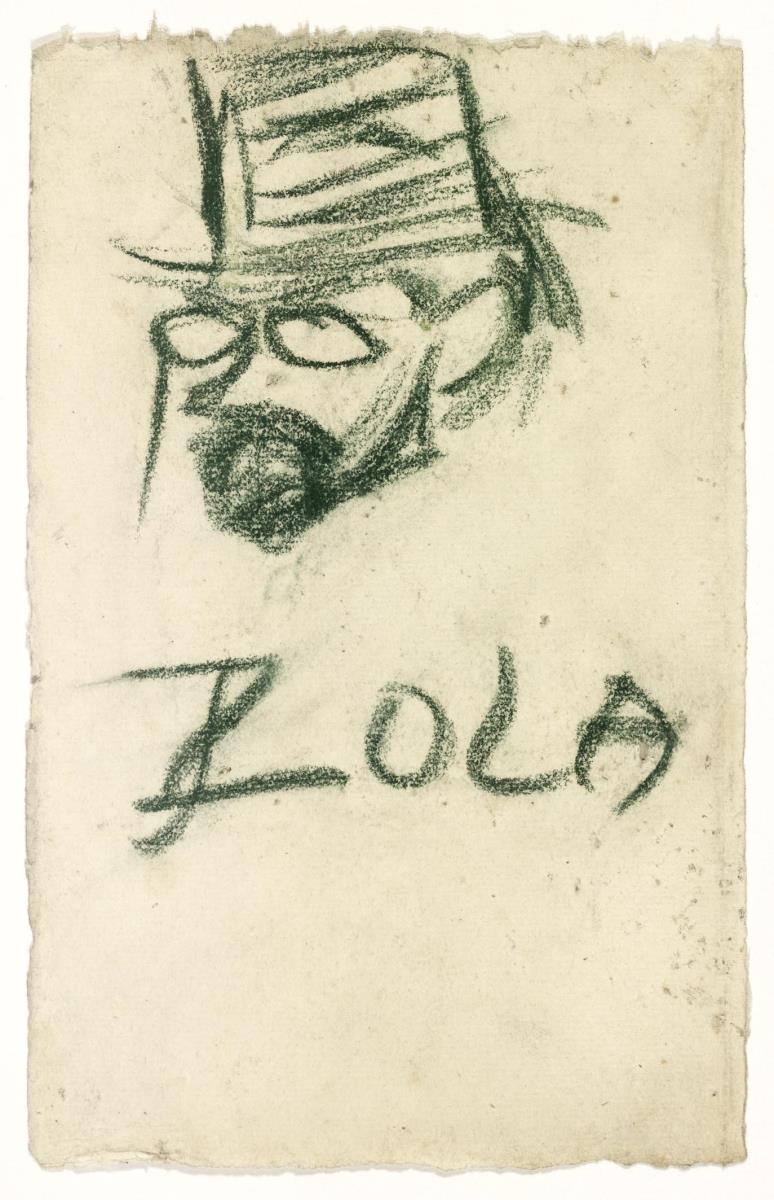

Picasso made his first trip to Paris in September 1900, where some years before Rusiñol had made several sojourns and integrated himself in the late-century modernity, rubbing shoulders with some of the leading figures in the arts. During his time in Paris, Rusiñol gradually forged an image of a modern man of the arts, both as a painter and as a writer. It is generally accepted that Rusiñol's and Ramon Casas's stays to Paris marked a turning point in the evolution of Catalan art. From the iconographic point of view, there are certain similarities between Picasso's first stay in Paris and Rusiñol's works centred on the neighbourhood of Montmartre. From the literary point of view, Rusiñol wrote numerous articles reporting on his experiences in fin-de-siècle Paris; in doing so, he contributed to the modernization of Barcelona and strengthened the existing artistic ties between the two cities. Finally, he had an indirect influence on Picasso, to the extent that, like any artist living in Barcelona, he benefited from the avant-garde and modern Rusiñol.

The Artist's Condition

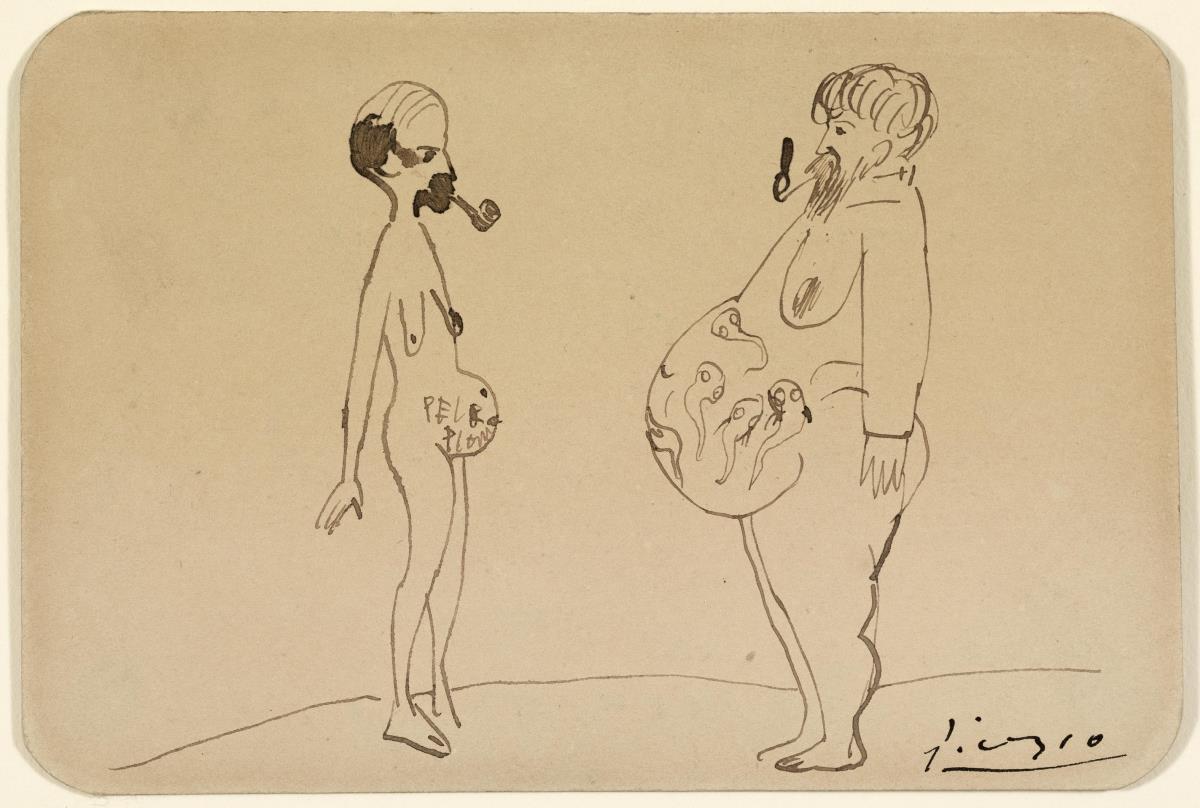

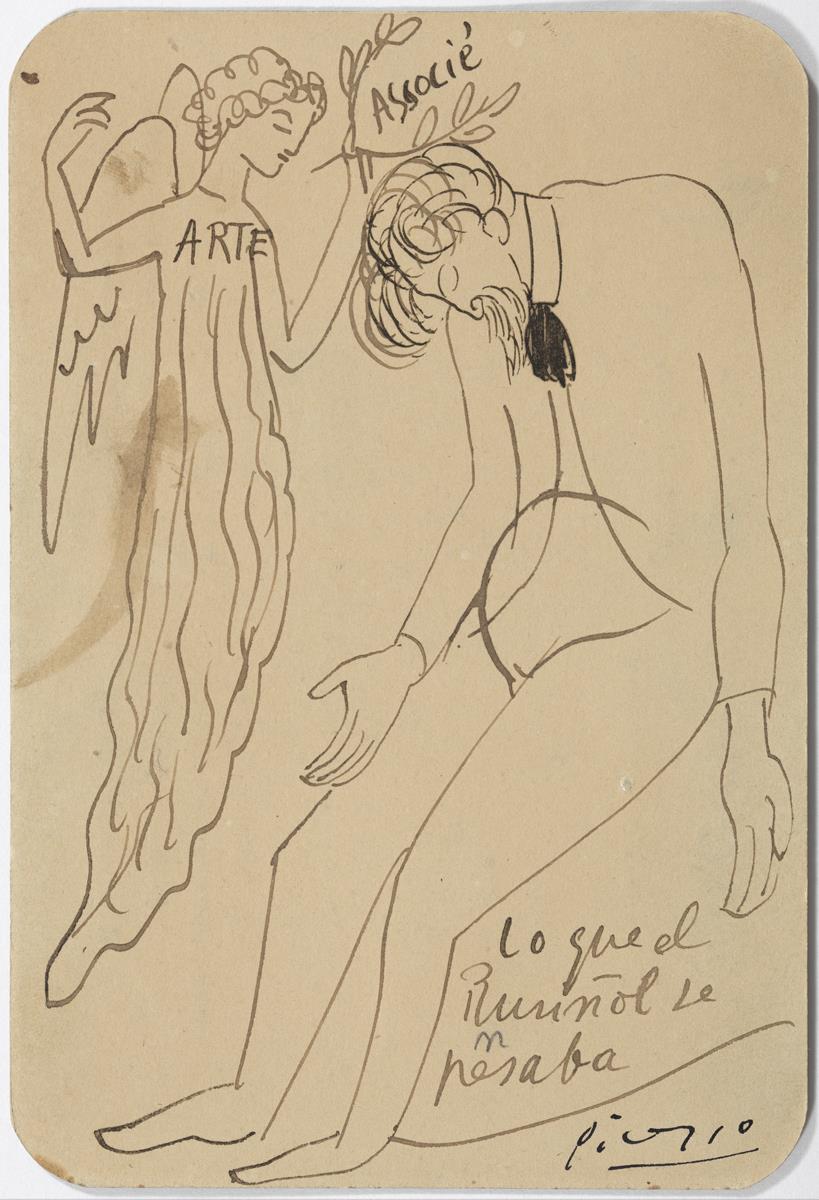

At this early point in his life, one of Picasso's main concerns was the condition of the artist in general, but also with his own need to create an image for himself. Picasso first became interested in Rusiñol at the end of his academic training, that is, just as his mindset was shifting from that of a student to that of an artist. Some of the most notable reflections found in Rusiñol's oeuvre also had to do with the figure of the artist, as in L'alegria que passa [The Joy that Passes], which centred on how the artist fits into society, a theme also found Picasso's work. Along with Ramon Casas, Rusiñol represented the archetype of the successful artist Picasso knew best in his Barcelona years, and he did portraits of both, separately as well as together. But Picasso followed neither of these models in the future; the only thing that really interested him was the “Picasso model”. The others were there to serve him, to the extent that at one time or another they might be useful in creating his own.

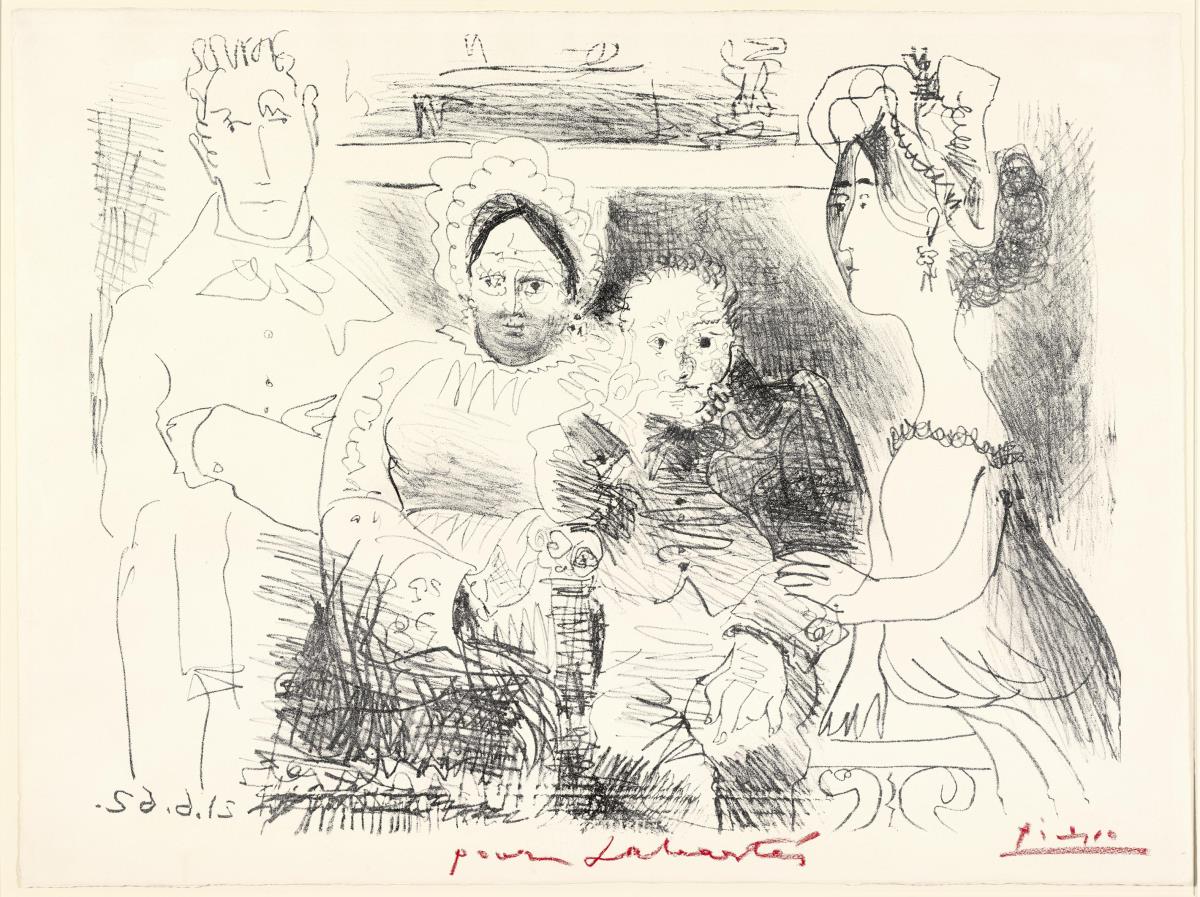

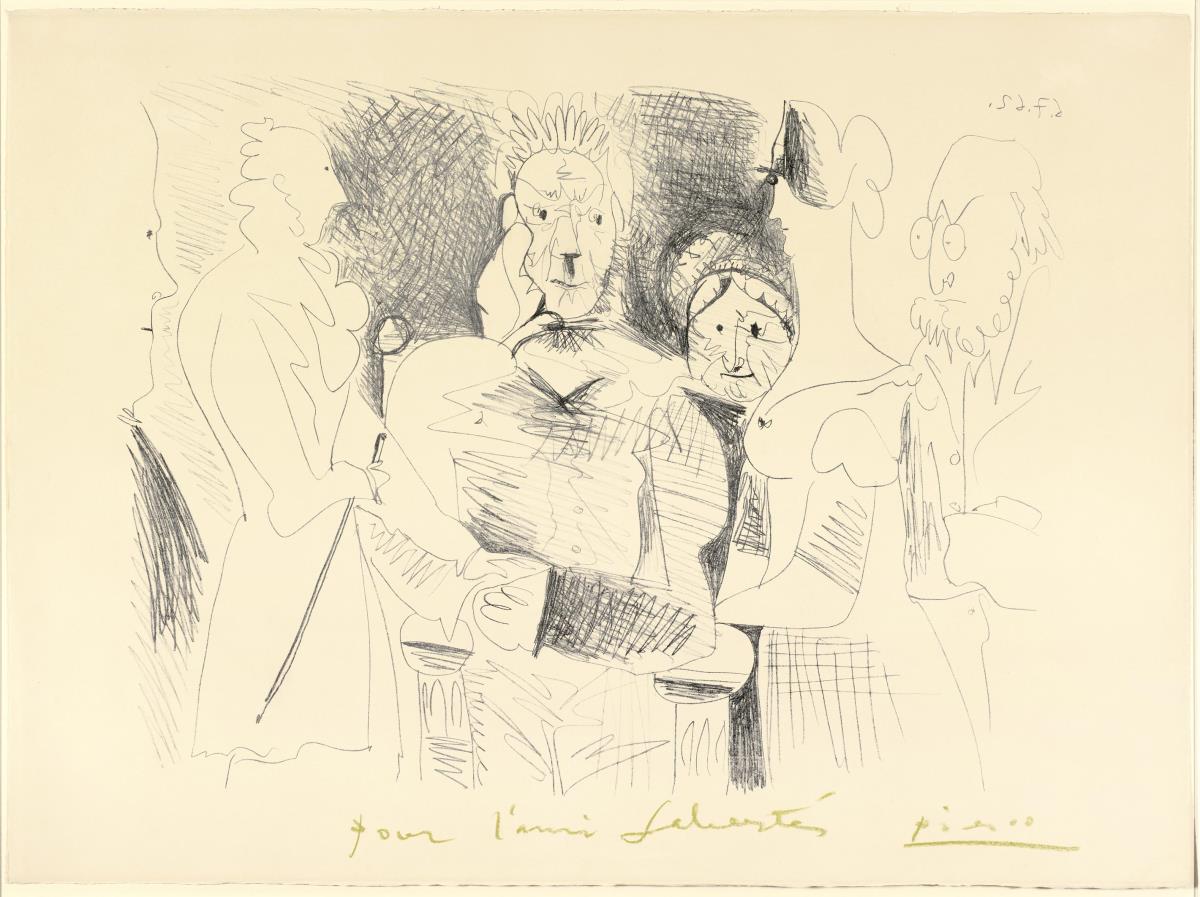

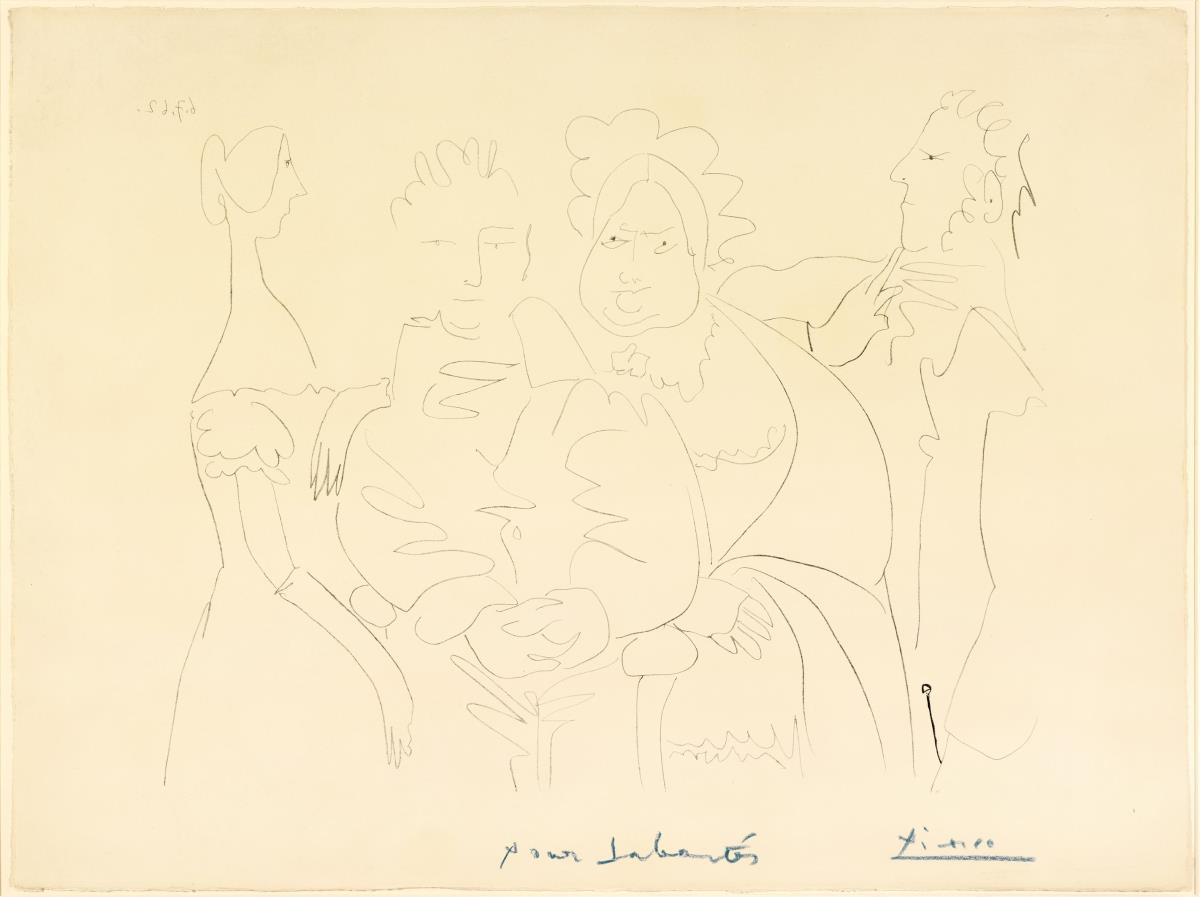

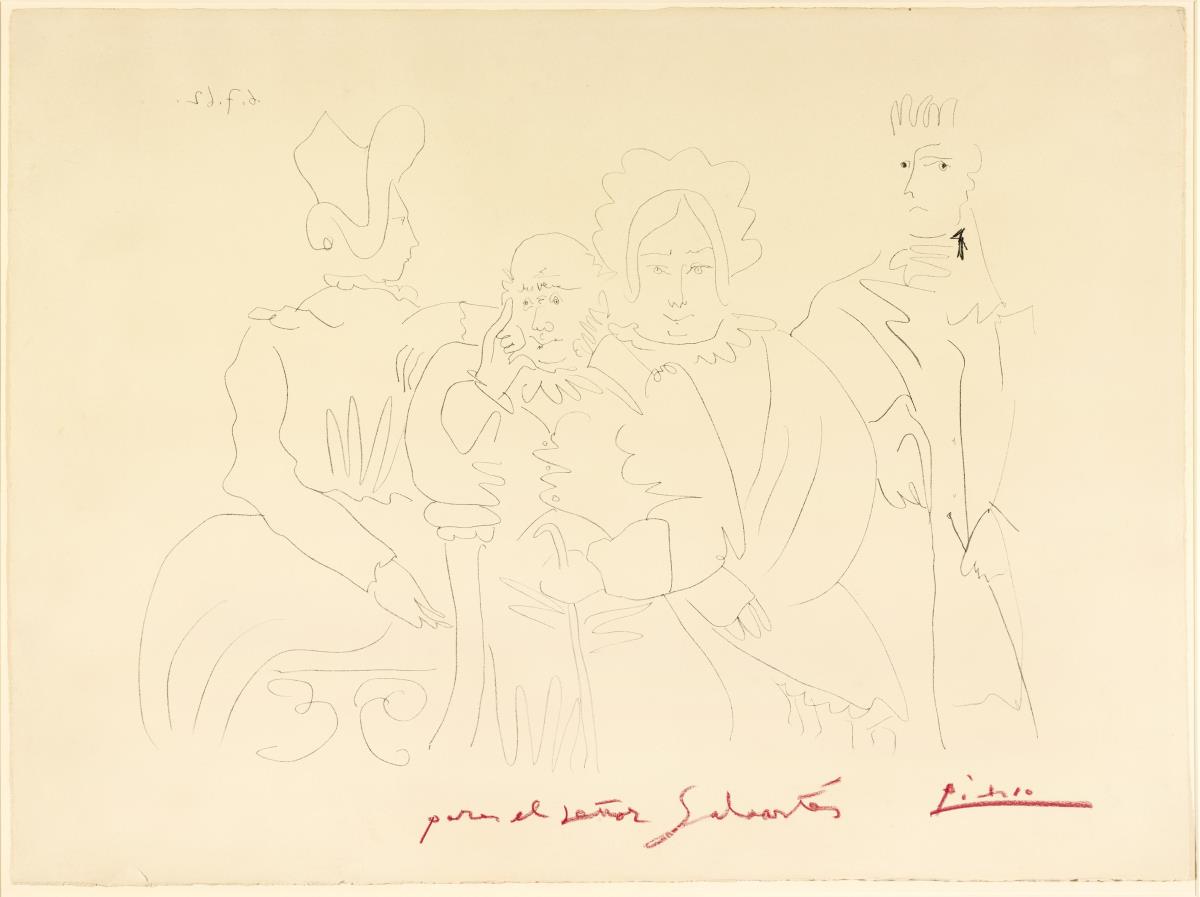

The Artist's Condition. L’auca del senyor Esteve

During the period 1962 to 1964, more than three decades after the death of Rusiñol, Picasso did some free illustrations based on one of Rusiñol's most important literary works: L’auca del senyor Esteve. Picasso took renewed interest in a work by Rusiñol that focused on the relationship between the artist and society. These illustrations were part of a larger process of revisiting both the history of art and his own past. In L’auca del senyor Esteve Picasso could recognize the Barcelona of his adolescence and early adulthood, the setting for the novel. This interest must have been heightened by a renewed connection with Barcelona in anticipation of the opening of the Picasso Museum in 1963. The inspiration behind these illustrations has not always been acknowledged in the titles they have been given, despite the fact that Picasso himself told several critics and gallery owners that they were based on Rusiñol's book. All the illustrations are very similar in terms of composition, but they embrace a considerable range of techniques, including drawing, lithography, linoleum and ceramics. Some of the lithographs were subsequently coloured by Picasso, and in some cases even borrow elements from the illustrations Ramon Casas did for the novel at the beginning of the century.

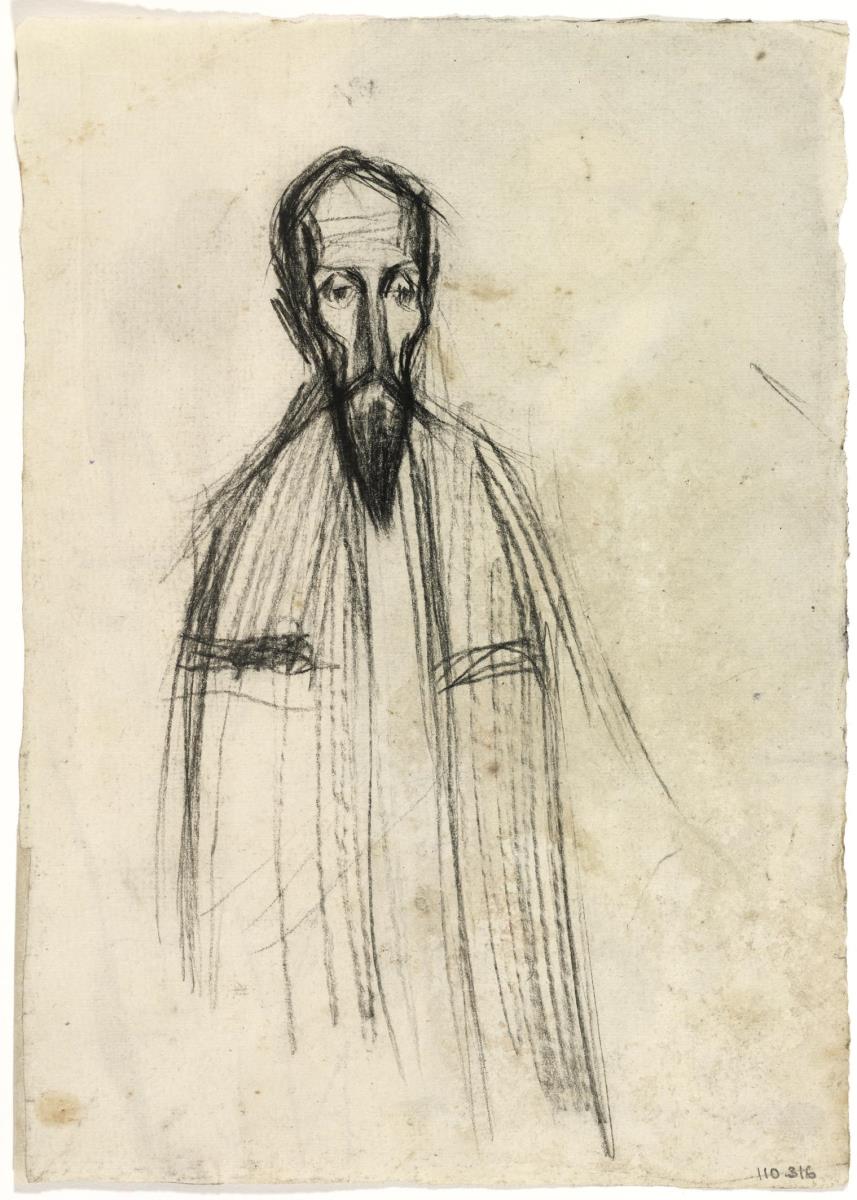

El Greco, Rusiñol and Picasso

In 1899 Picasso did a portrait of Rusiñol hybridized as the anonymous figure in El Greco's Knight with his Hand on his Breast, in recognition of the former's role as a champion of the Cretan master. Although not the only one involved in El Greco's rehabilitation, Rusiñol was its prime instigator in Barcelona and the one Picasso knew best. Rusiñol was behind an entire campaign in favour of El Greco: he bought two of his paintings; he organized their quasi-religious procession to Cau Ferrat, his home and studio; he promoted a popular subscription for a monument to El Greco; he wrote about him; in sum he engaged in a lively proselytising that affected many other artists, including Picasso. At the time of this campaign, there began to appear among Picasso's works numerous instances of El Greco's influence, the strength of which that cannot be accounted for in the absence of Rusiñol's efforts. Although Picasso had seen El Greco's work before, at Cau Ferrat he could now see originals, along with many copies of and works influenced by this artist. Traces of El Greco can be seen in Picasso's work until the last years of his life. In the nineteen-forties, when he told Brassaï that “El Greco has seen better times”, doubtless he was referring to the campaign led by Rusiñol, when El Greco's paintings were borne through the streets like saints and monuments were erected in his memory.

Picasso Paints the Gardens of Rusiñol

In 1901 the magazine Arte Joven, which Picasso co-edited, published a portrait of his of Rusiñol in the setting from one of the latter's garden paintings. That portrait was originally meant to be part of a special Rusiñol issue that Picasso wanted to do but that was never published. Still, the issue dedicated more space to Rusiñol than to any other artist, including one of his short stories and a very favourable review of his gardens. With this green portrait — same the colour that monopolized Rusiñol's garden paintings — Picasso acknowledged Rusiñol's role as a leading painter of a theme in which at the time Picasso showed periodic interest, although landscapes — still less gardens — were never among his preferred subjects. Some years earlier, in the period 1897 to 1898, Picasso had painted several gardens and rural roads along the lines of Rusiñol, even if the influences were more diffuse. Picasso had moved to Madrid to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, but he often missed his classes and produced a number of very dreamy works that evoked Rusiñol.

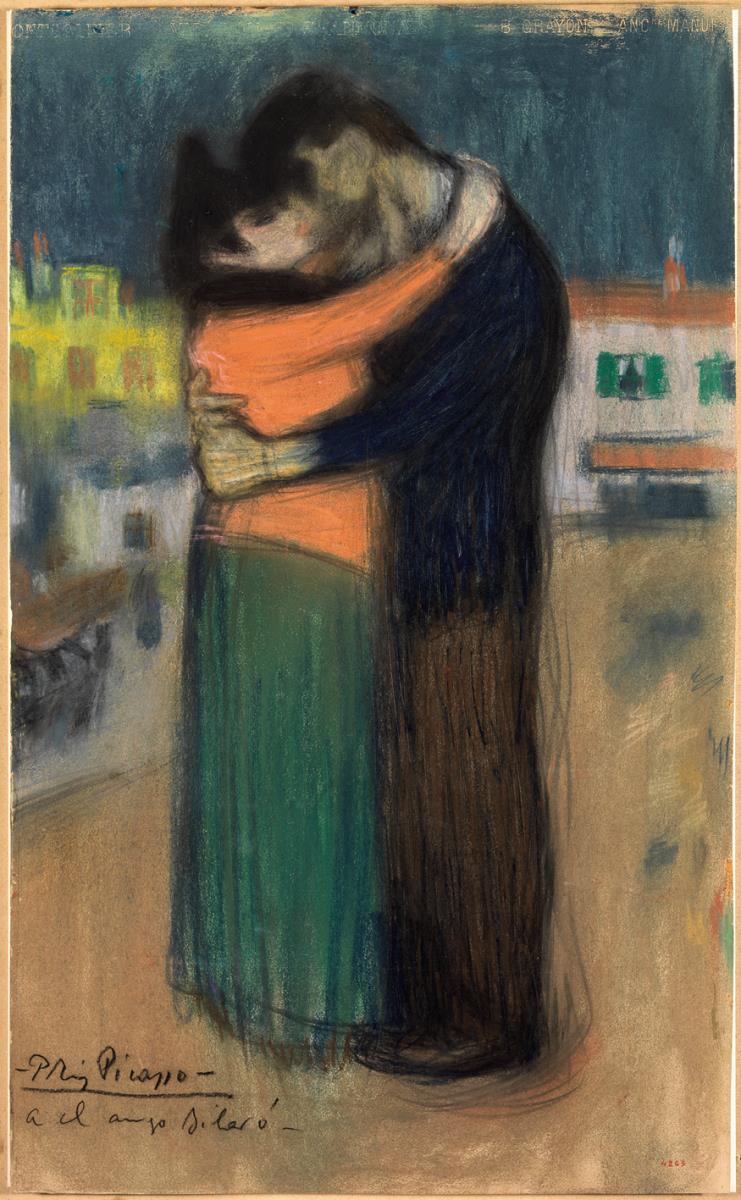

Creation of Atmospheres: Blue in Context

Beyond the many influences that are usually associated with Picasso's Blue Period, strictly in terms of colour we mustn't forget that blue had a long tradition in European literature and painting, including in Barcelona. When Lafuente Ferrari said “Picasso didn't need to wait to get to Paris to be won over by blue”, he meant precisely the importance that the colour had acquired in Picasso's most immediate surroundings because of artists like Rusiñol. Rusiñol's role in the use of blue is well known; he was among its most distinguished proponents and it has considerable prominence in his work: it appears in his courtyards (both pictorial and literary), in his landscapes, portraits and in his other writings. In 1901, at the start of his Blue Period, Picasso published in the magazine Arte Joven Rusiñol's short story “El patio azul” [The Blue Courtyard], a tribute to a colour that, with their respective differences, both artists used, including in the same period.

Illness and Death

During his Barcelona years, Picasso did several works on the theme of illness and death, mostly during his tenebrist period, between 1899 and 1900. According to John Richardson, Rusiñol's works dealing with death and morphine addiction “reaffirmed Picasso's morbid preoccupations”. Rusiñol was one of the main representatives of these discourses, in his two often inseparable facets as a painter and as a writer. Some years later, Picasso dealt with these same themes, and, although more claustrophobic and Expressionist, his approach was sometimes similar to that of Rusiñol in terms of atmosphere and composition. Like Rusiñol, he took a distinctly modern tack that stressed the atmospheric presence of the illness over the figure of the actual sufferer. Picasso dealt with this issue in a harsh and uncompromising set of works, but also with allegory and even irony.

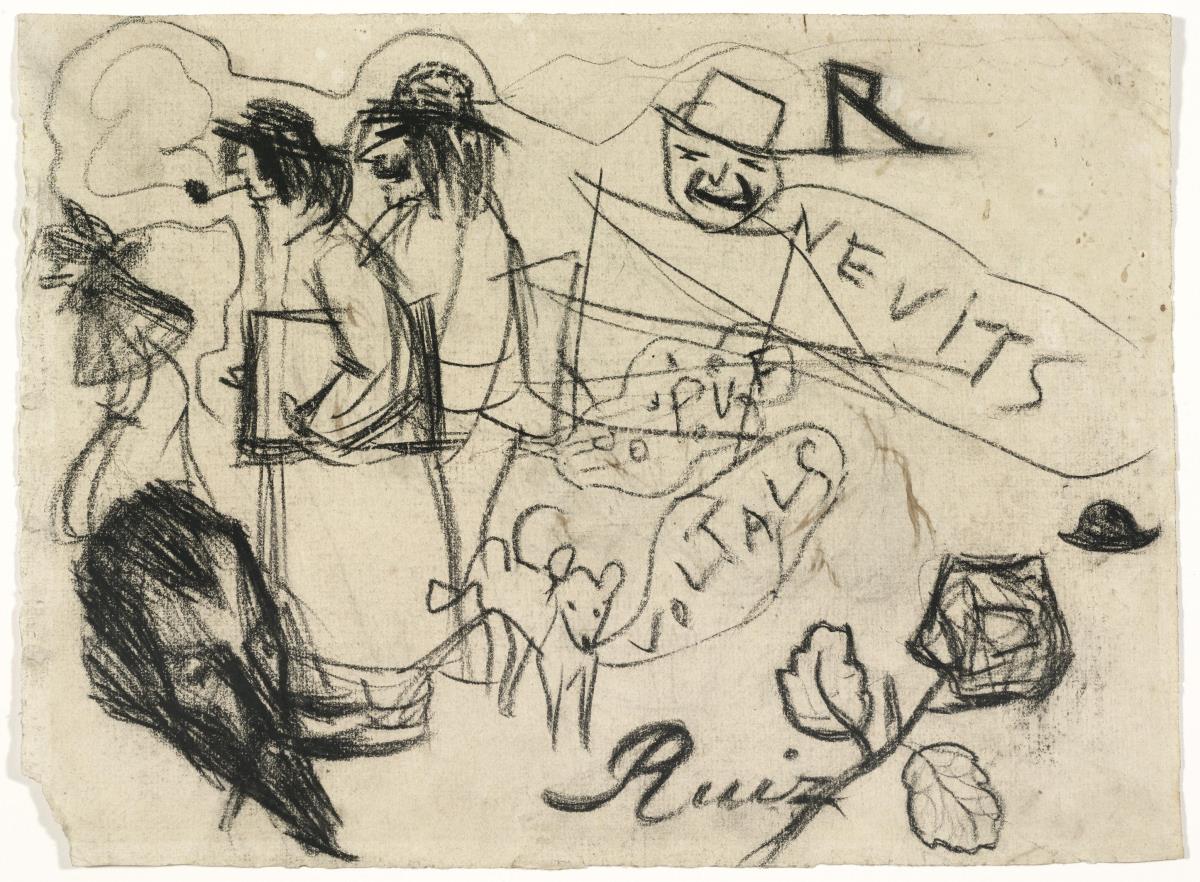

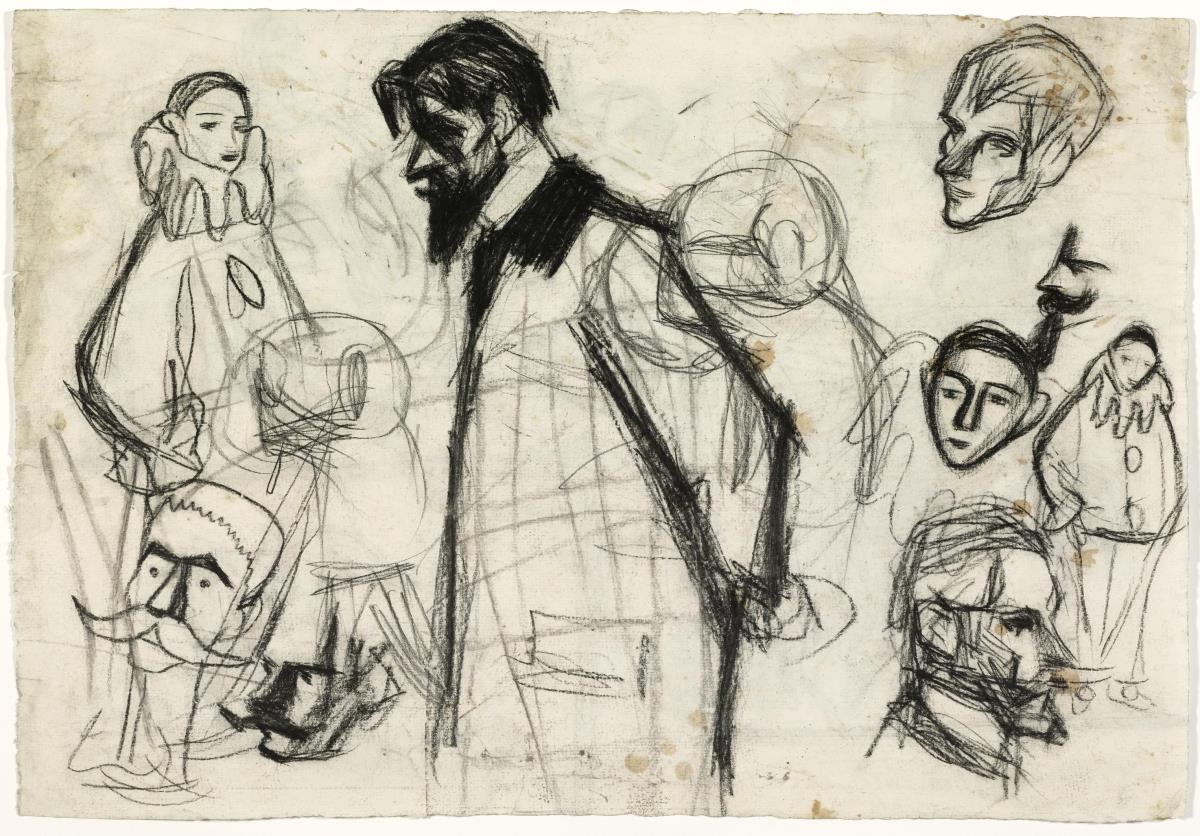

From homage to satire

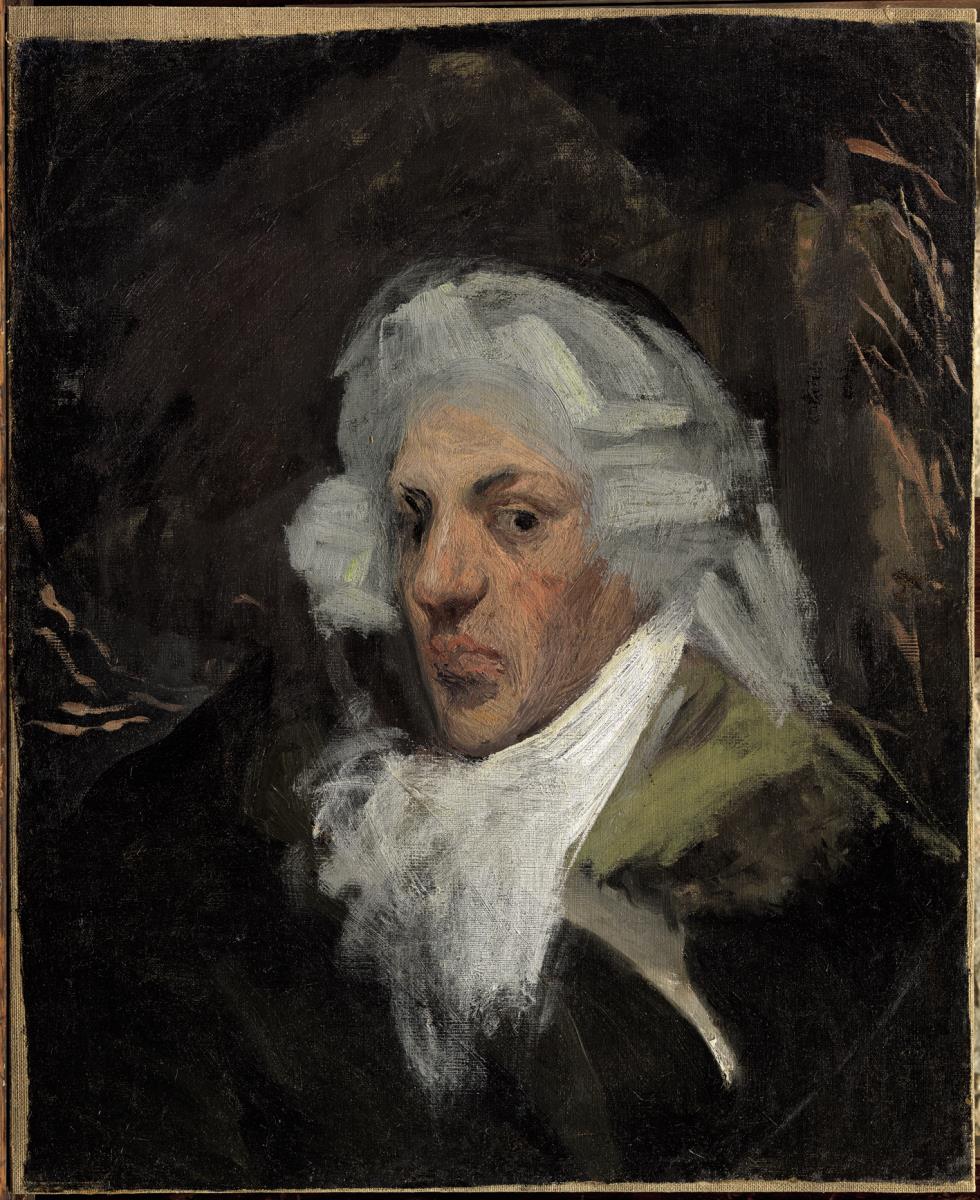

“Picasso works very little now: He thinks of going to Paris, and that idea distracts him; he paints reluctantly. Like all the youths who have lived in Paris, Picasso misses [...] the fever of the big city. He thinks of himself as ““passing through”” here in Barcelona.” This striking statement by the critic Miquel Sarmiento is from March 1904, a month before Picasso finally moved to Paris. Picasso's second stay in that city, from June 1901 to January 1902, marked a turning point in his career. During those months he showed works at the Vollard Gallery, received good reviews and started to make new friends and meet dealers and critics. In short, he was introducing himself in an art scene that completely different from Barcelona, where he discovered new intellectual paradigms and professional perspectives. From 1902 to 1904, when Picasso lived between Barcelona and Paris, there began to emerge new portraits of Rusiñol that denoted a distancing from the man, and the serious and respectful tone of the past became ironic, even satirical. The last portraits he did of Rusiñol illustrate Picasso's attitude towards the artistic status quo as well as towards one of its most emblematic figures.

!["Poeta decadente" [Jaume Sabartés]]( https://colleccions.eicub.net/api/1/images/https%3A%2F%2Fdobubt4dam3m5.cloudfront.net%2Fpublic%2FHeritageObject%2FH289212%2F142057%2Ffull%2Foriginal%2F0%2Fdefault.jpg)