Yo Picasso. Self-Portraits

This is the first large monographic exhibition on Picasso's self-portraiture, a genre that runs through over seventy years of the artist's life, from his childhood to death's door. In his self-portraits, Picasso bore witness to biographical facts, thoughts, worries and amusements and, above all, he used his own face as a laboratory of formal experimentations.

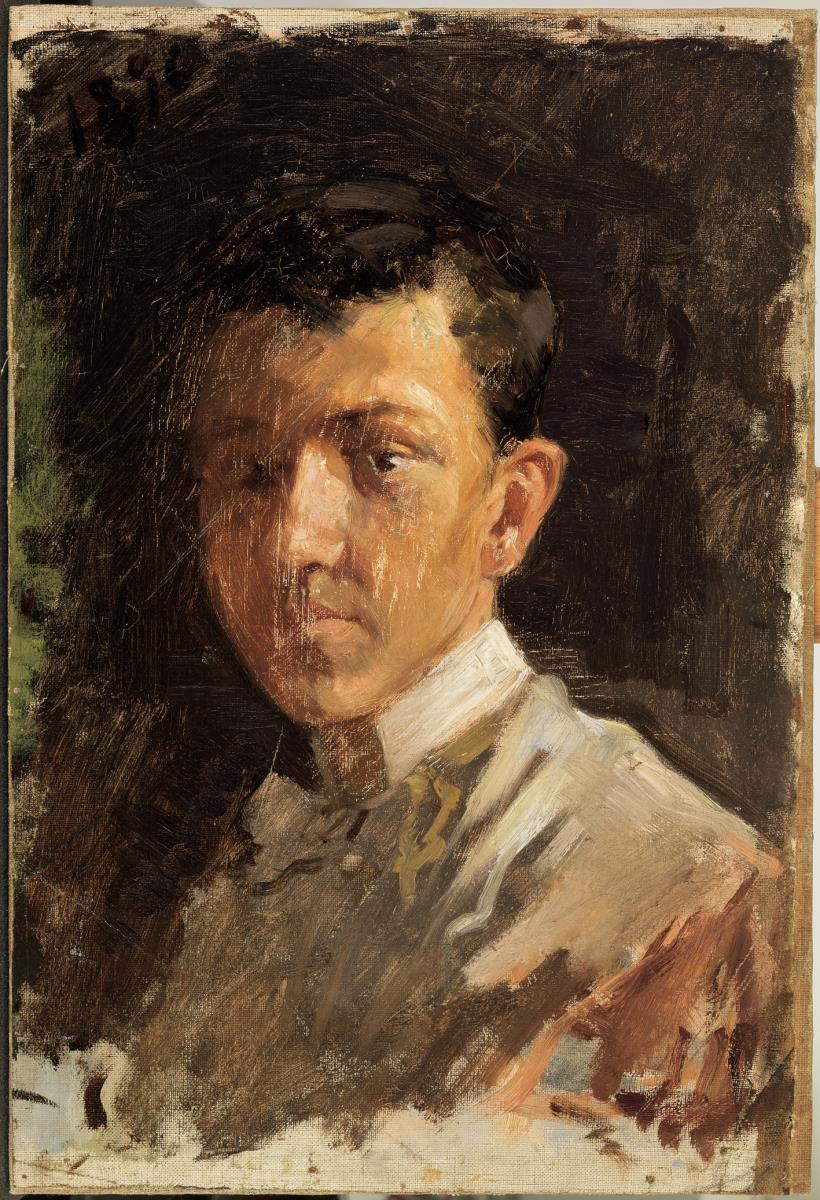

At the onset of the twentieth century, an impulsive Picasso who was barely twenty portrayed himself in several works convincingly signed 'Yo'. The euphonic quality of the expression conveyed the vigour and the self-confidence of an artist who would leave a strong impression on aesthetic developments of the century. In spite of this early interest in emphasising his sense of identity, self-portraiture as a genre was only really prominent during his youth, and to a lesser extent during his old age, thus establishing a continuity between both periods. In the interim, the traditional self-portrait became an exceptional theme that coexisted with several different types of self-representations.

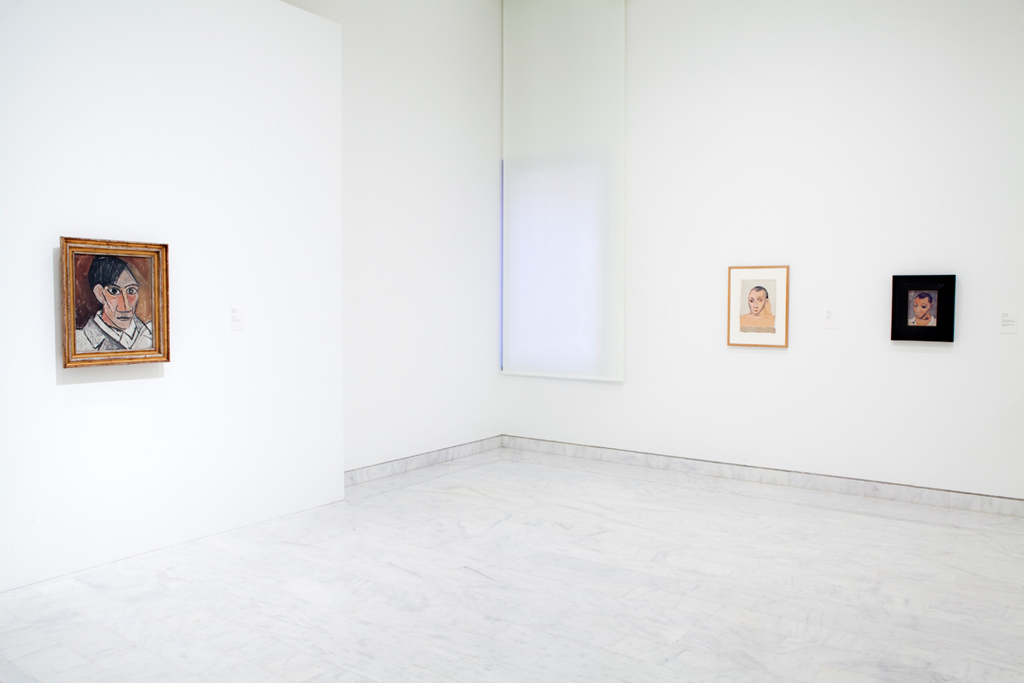

This is the first monographic exhibition dedicated to the self-portrait in Picasso's oeuvre. The installation of the works allow for a double interpretation: in the formalist sense, parallel to the development of his self-portraits, it enables us to follow the artist's career from his academic beginnings through his Blue Period, his Primitivist experiments, his Cubist, Neo-classicist and Surrealist ventures, and his late works; while in narrative terms, it explores in depth the strictly human aspects of a clearly autobiographical oeuvre.

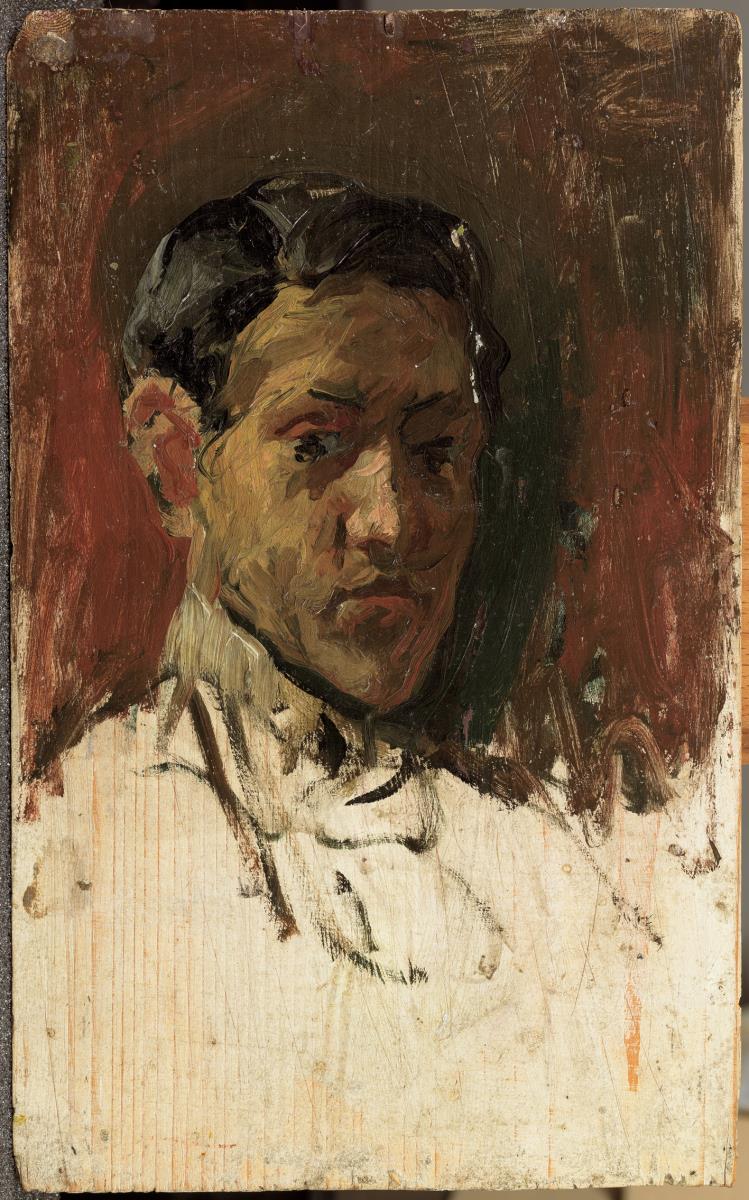

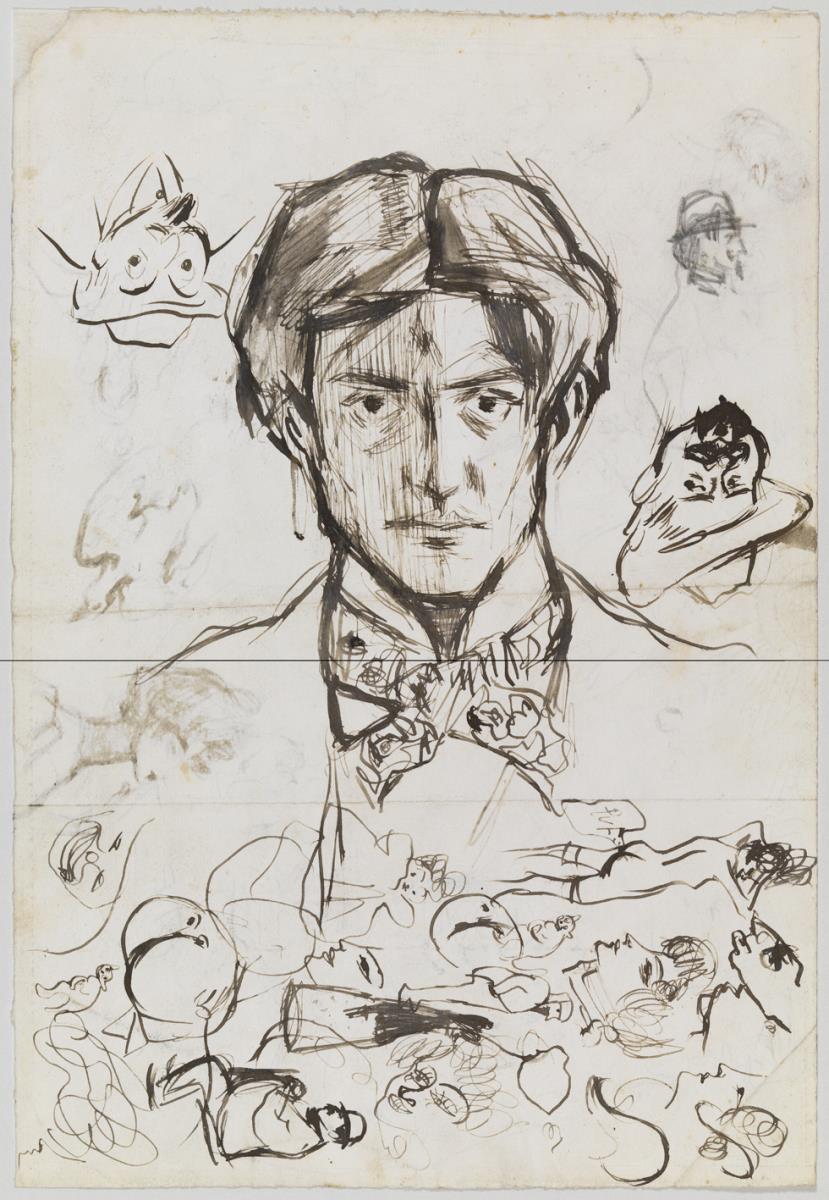

Barcelona, a factory of self-portraits

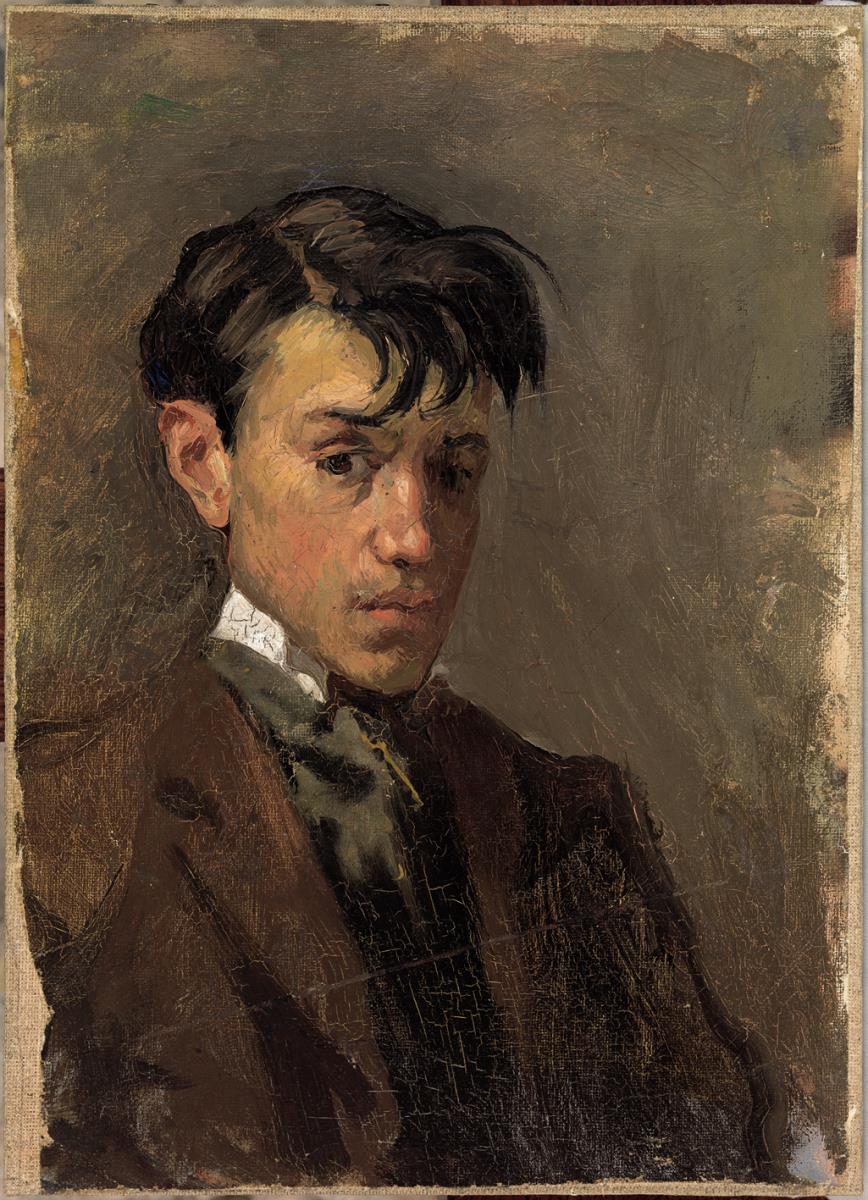

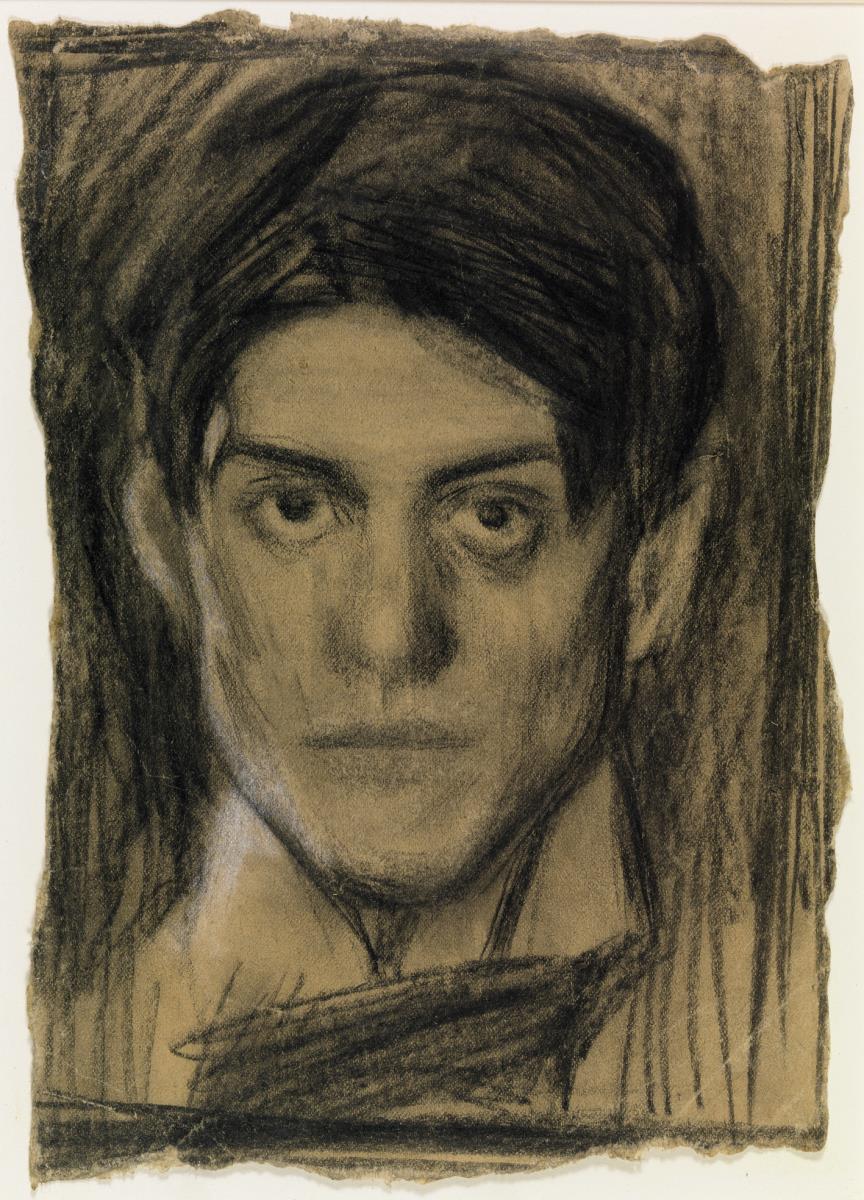

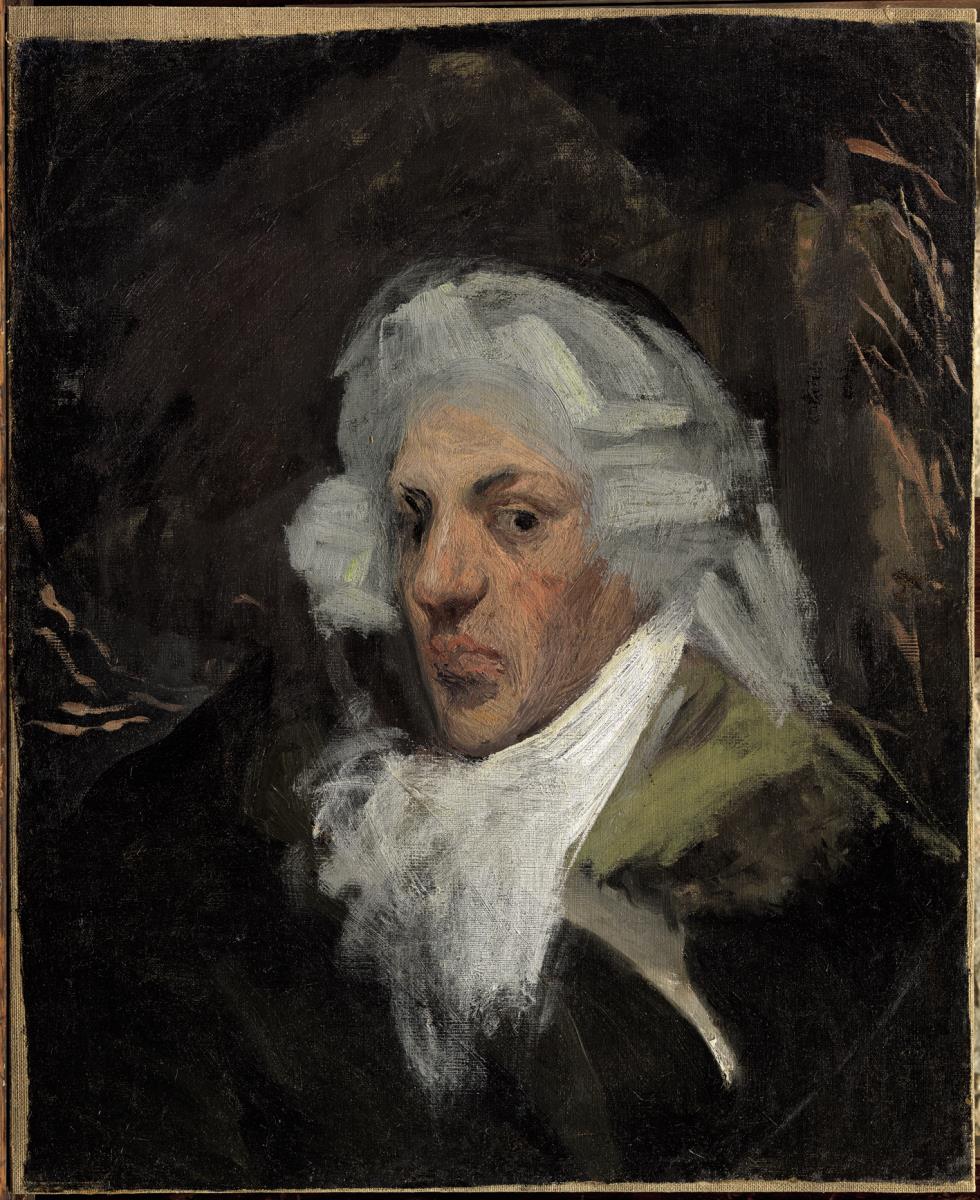

Picasso declared that 'Painting isn't a question of sensitivity; we need to usurp power; we need to take the place of nature instead of depending on the information she offers us'. From very early on, Picasso established a highly personal mode of self-representation, as a result of which his first self-portraits eluded the imitative quality of the genre, dispensing with his real physiognomy. This first area of the exhibition analyses the self-portrait by focusing on the face, the most prominent feature in his early production. Some of the works still reveal the artist's academic training, as exemplified by the ochres that filled his palette at the Llotja art school, although we also come across anti-academic methods that betray a strong personality. This initiation process is characterised by the need for self-assertion and a great command of draughtsmanship. Most of the self-portraits of his youth were produced in Barcelona, where he arrived at the age of thirteen, and this early period was the only one during which self-portraiture formed a substantial part of his oeuvre.

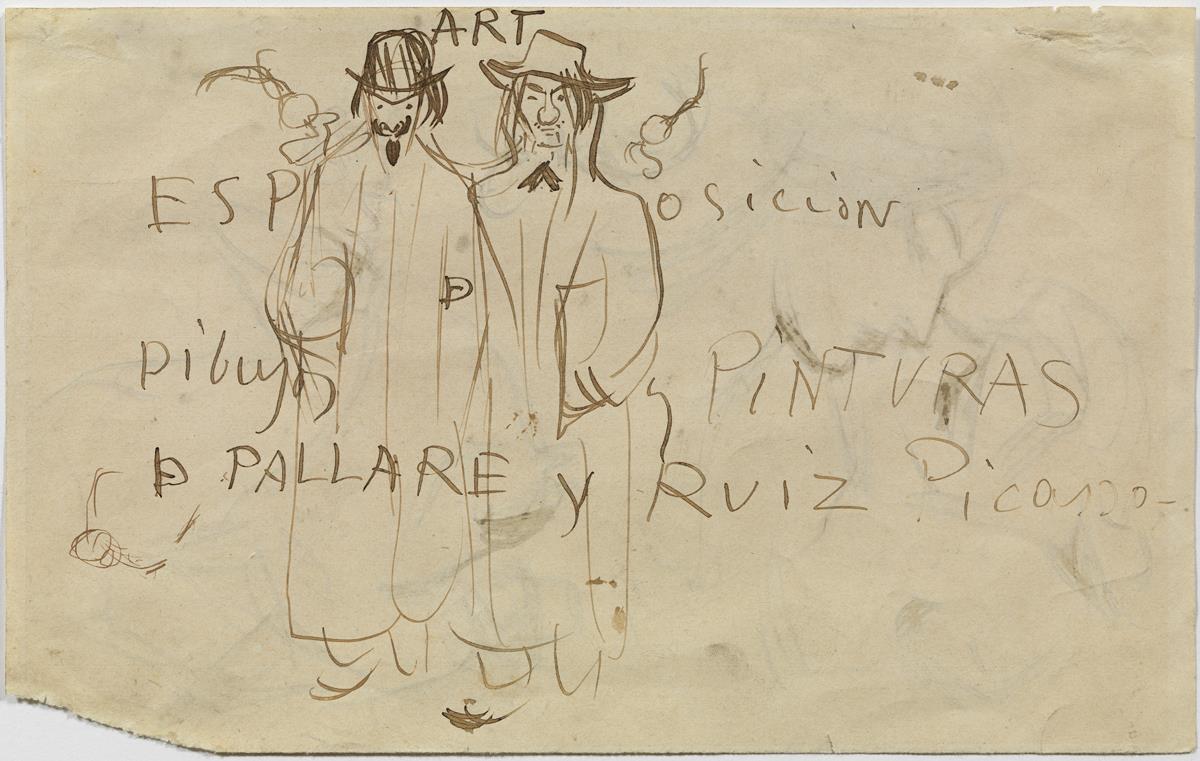

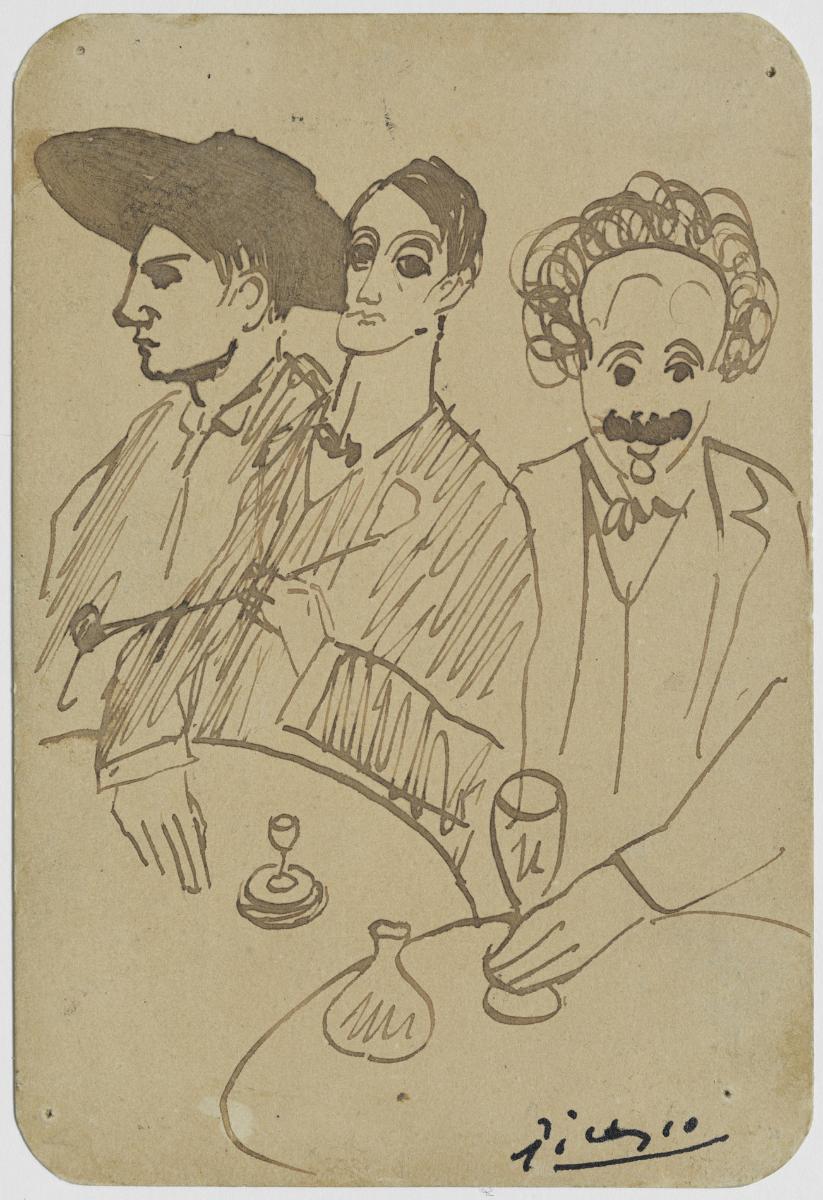

Forging the image of the creator

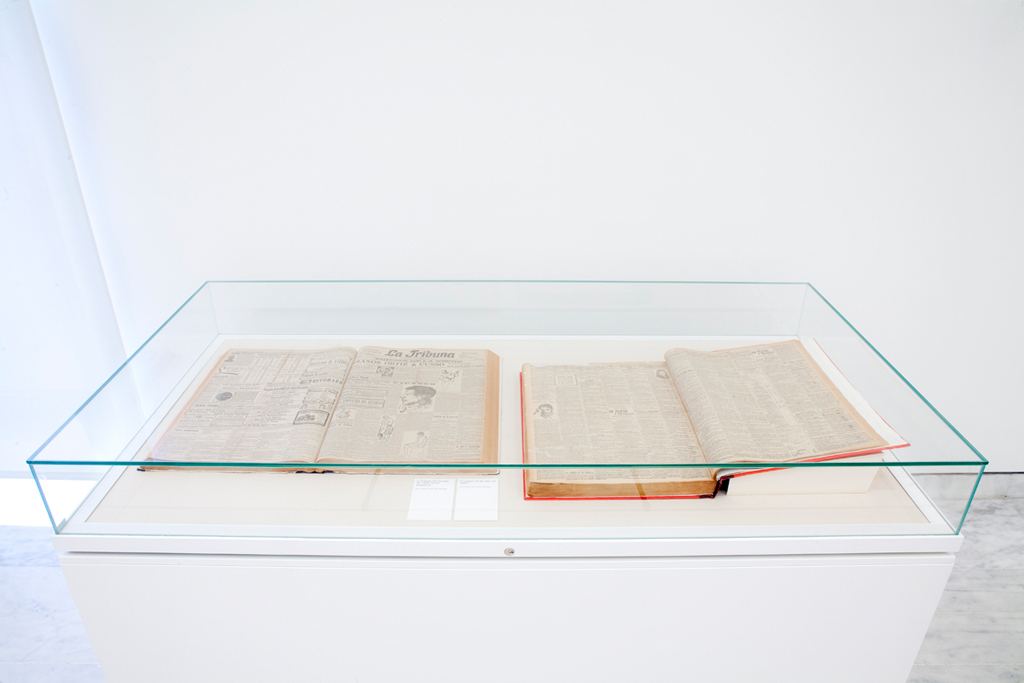

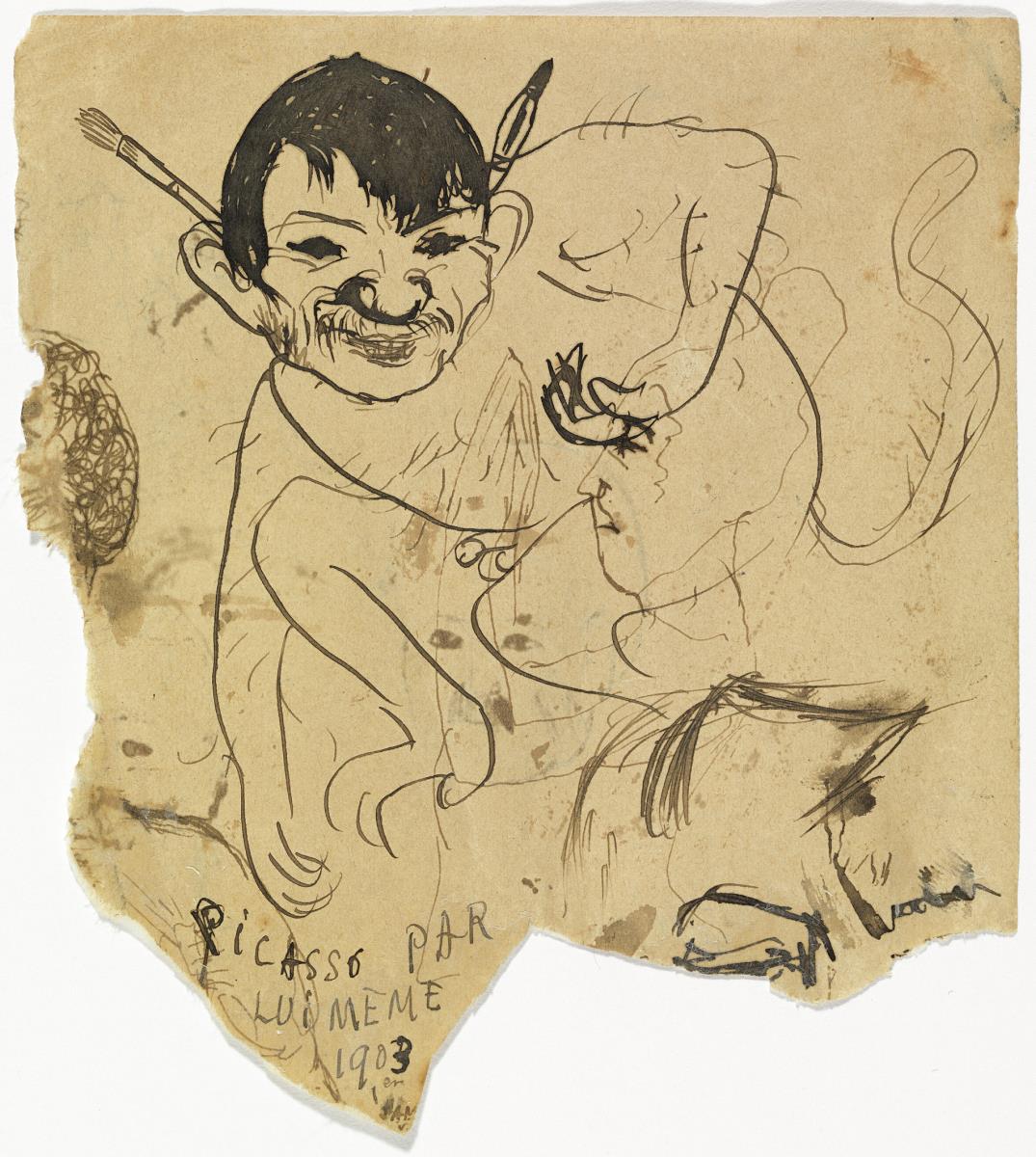

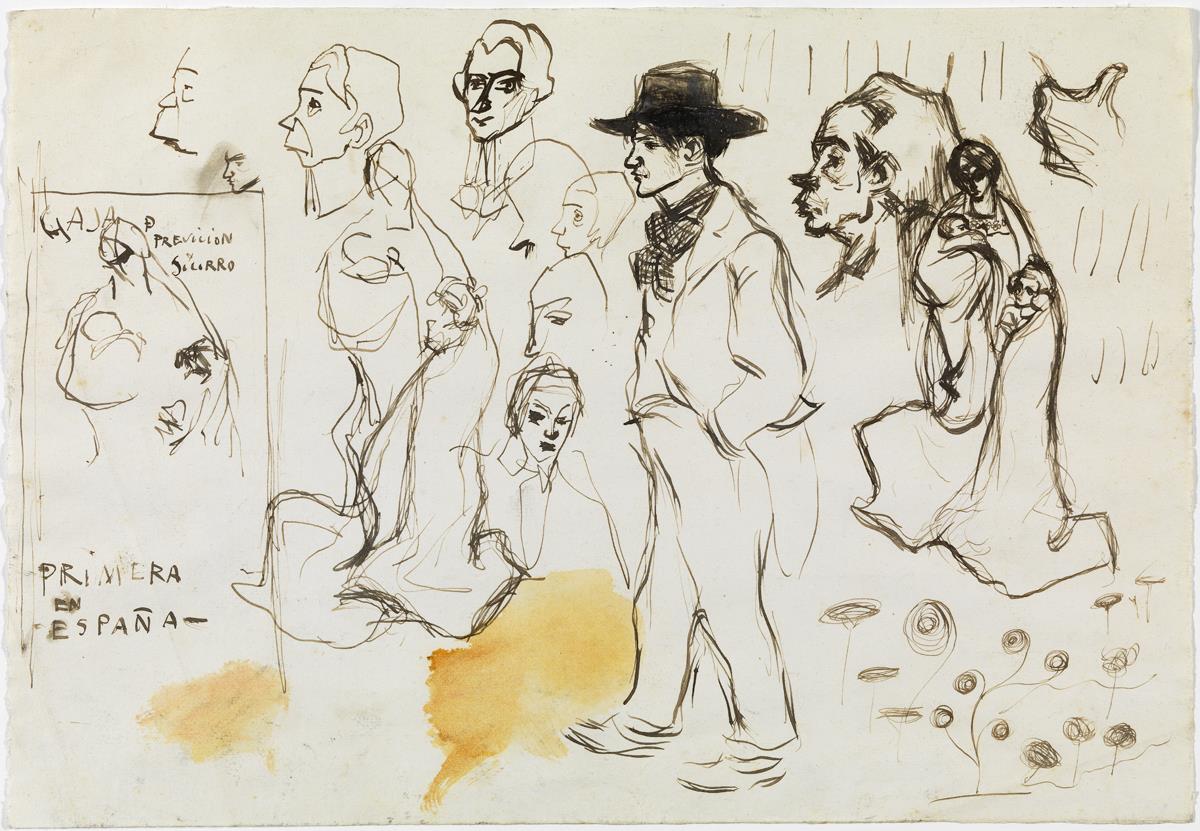

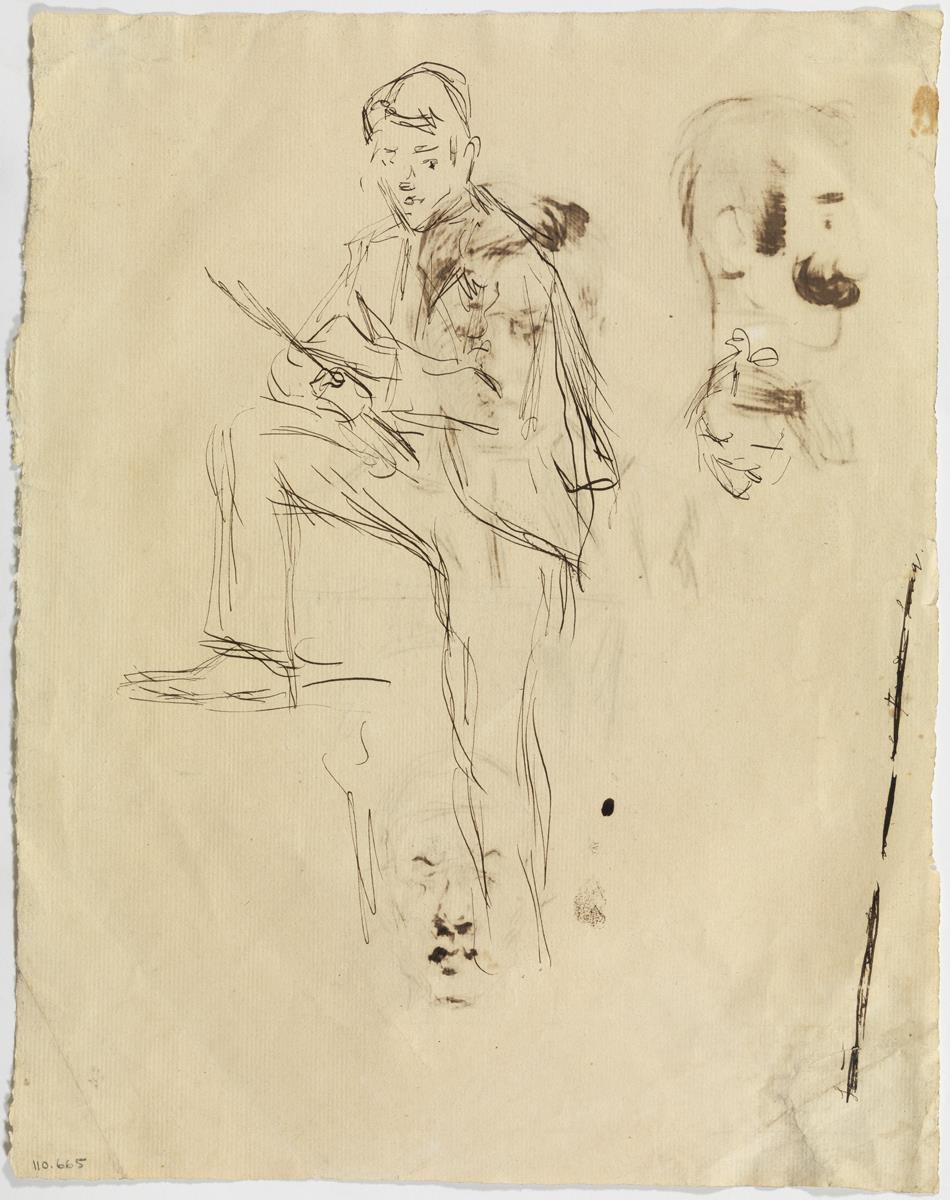

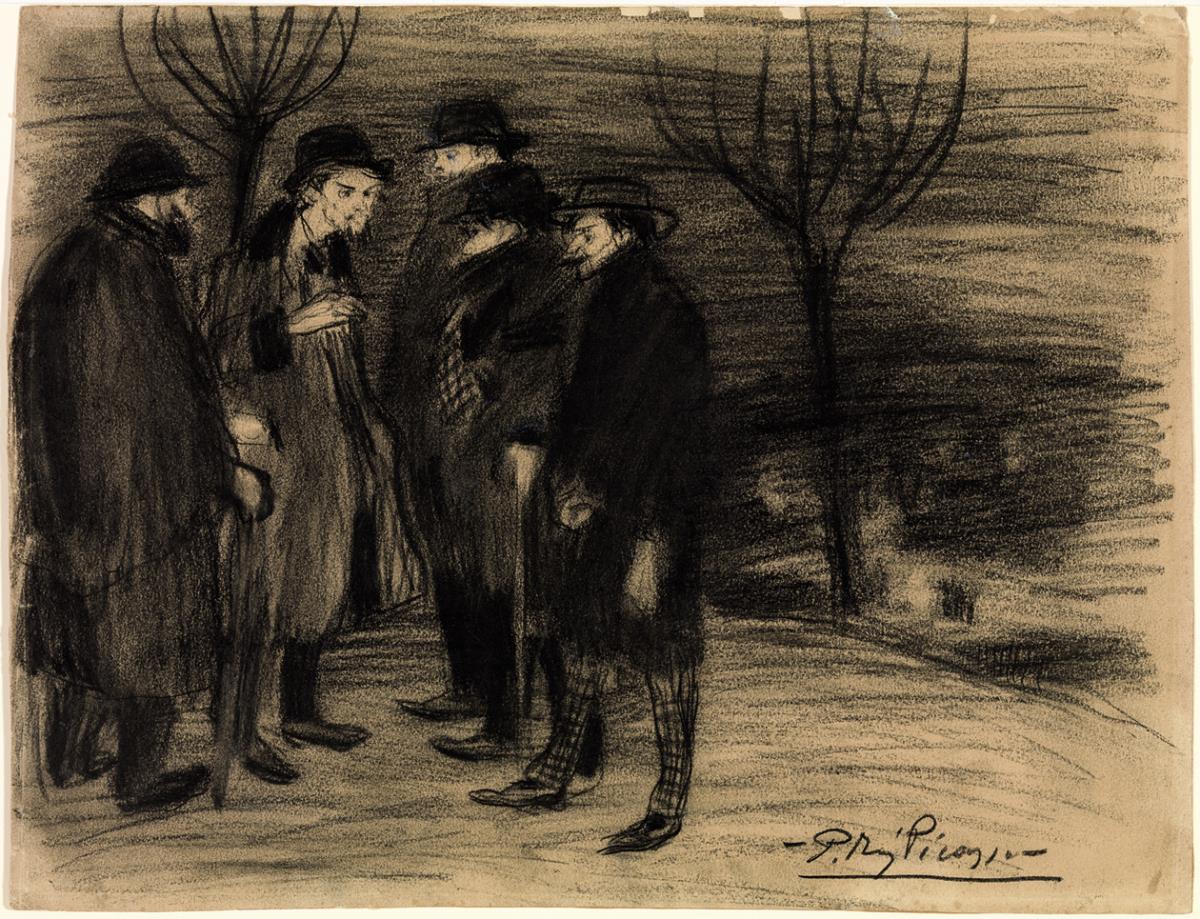

Picasso began to cultivate the variation of the self-portrait as an artist during his academic years and his youth, although the theme runs throughout his oeuvre. This process of self-objectification led him to experiment with all sorts of perspectives and postures, mirroring the old masters and emphasising his condition as an artist. The historical costume and the animalised double hybrid, two important categories in Picasso's self-representations, were often caricatured, as in Self-Portrait with Wig or ’Picasso par lui-même’, in which he portrays himself as an ape. His projection as an artist can be traced in several guises, either as a painter in the act of creating (before a canvas), or as a bohemian wearing outlandish clothes, accompanied by friends. In this promotional process he turned to the press, producing self-portraits for reviews published in Barcelona and for Arte Joven, a journal he co-edited.

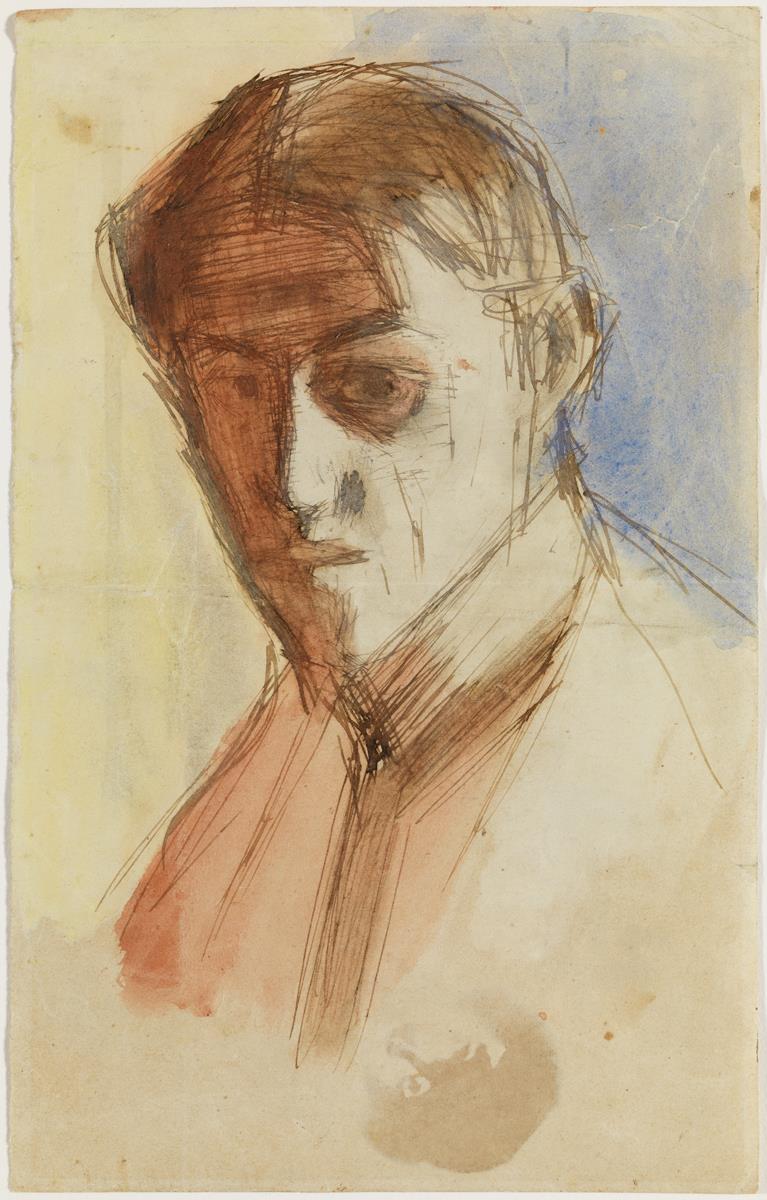

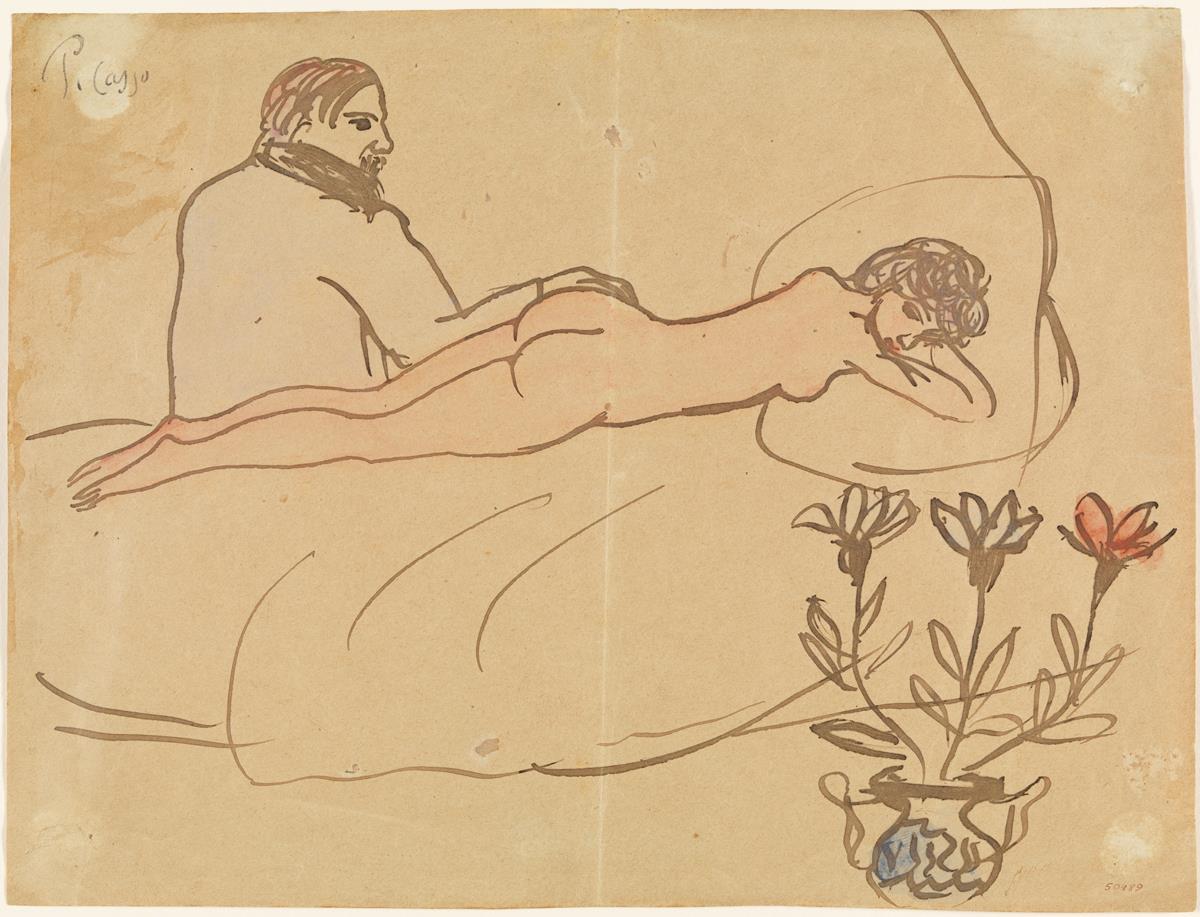

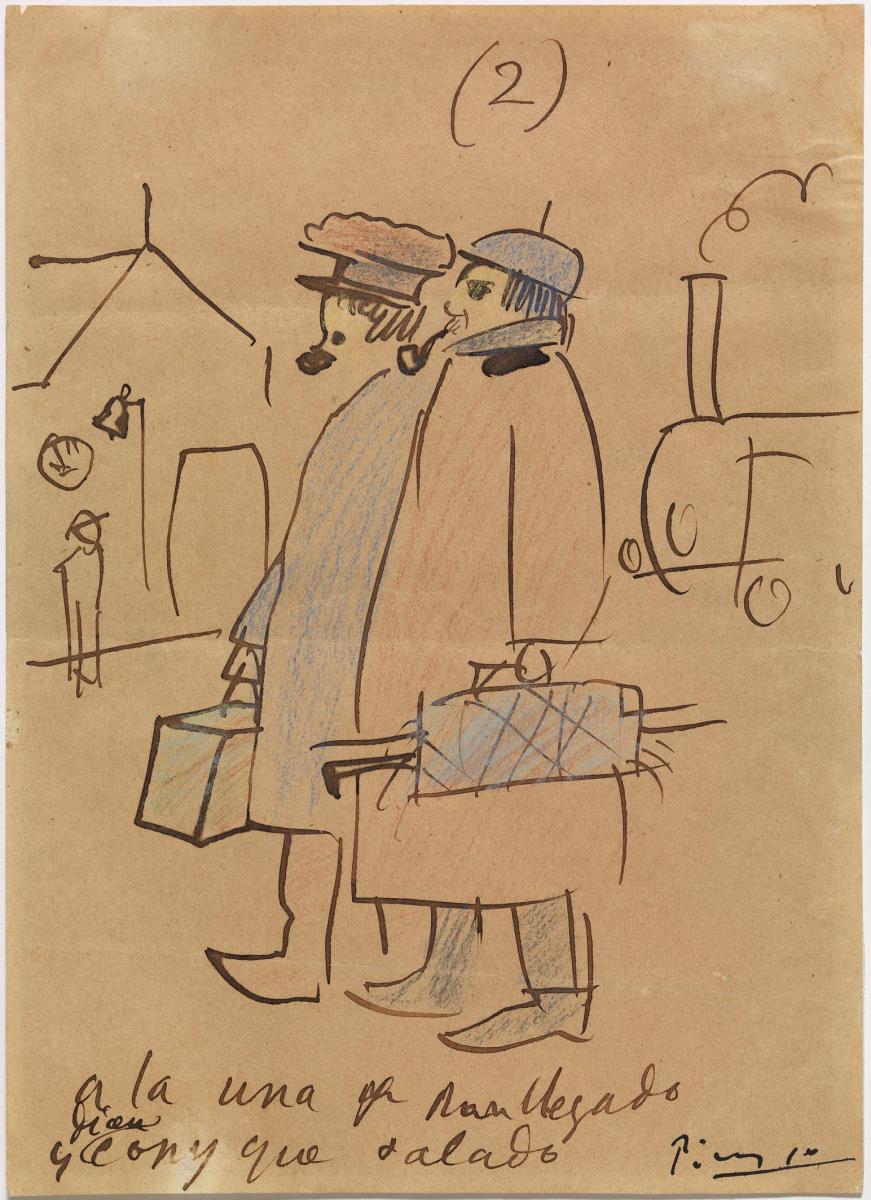

Eros, thanatos and life. Paris 1901

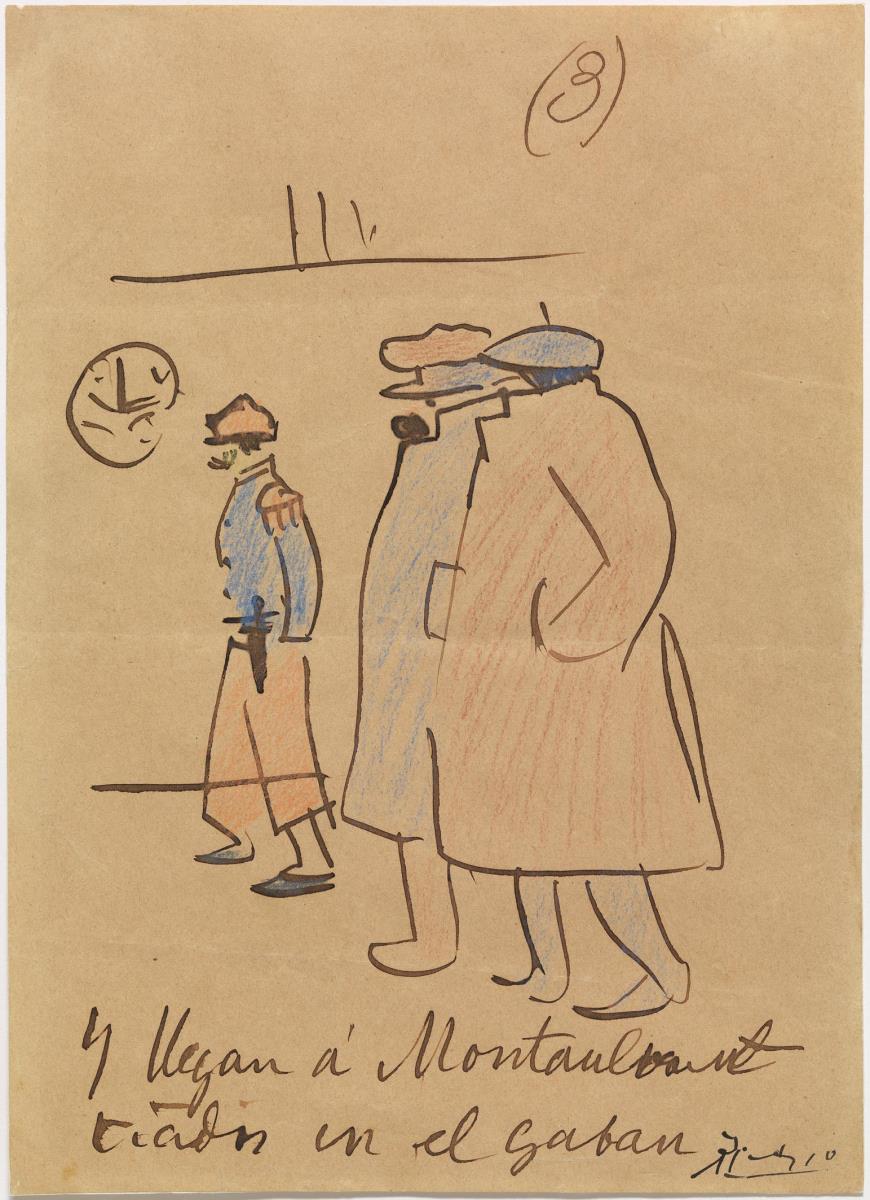

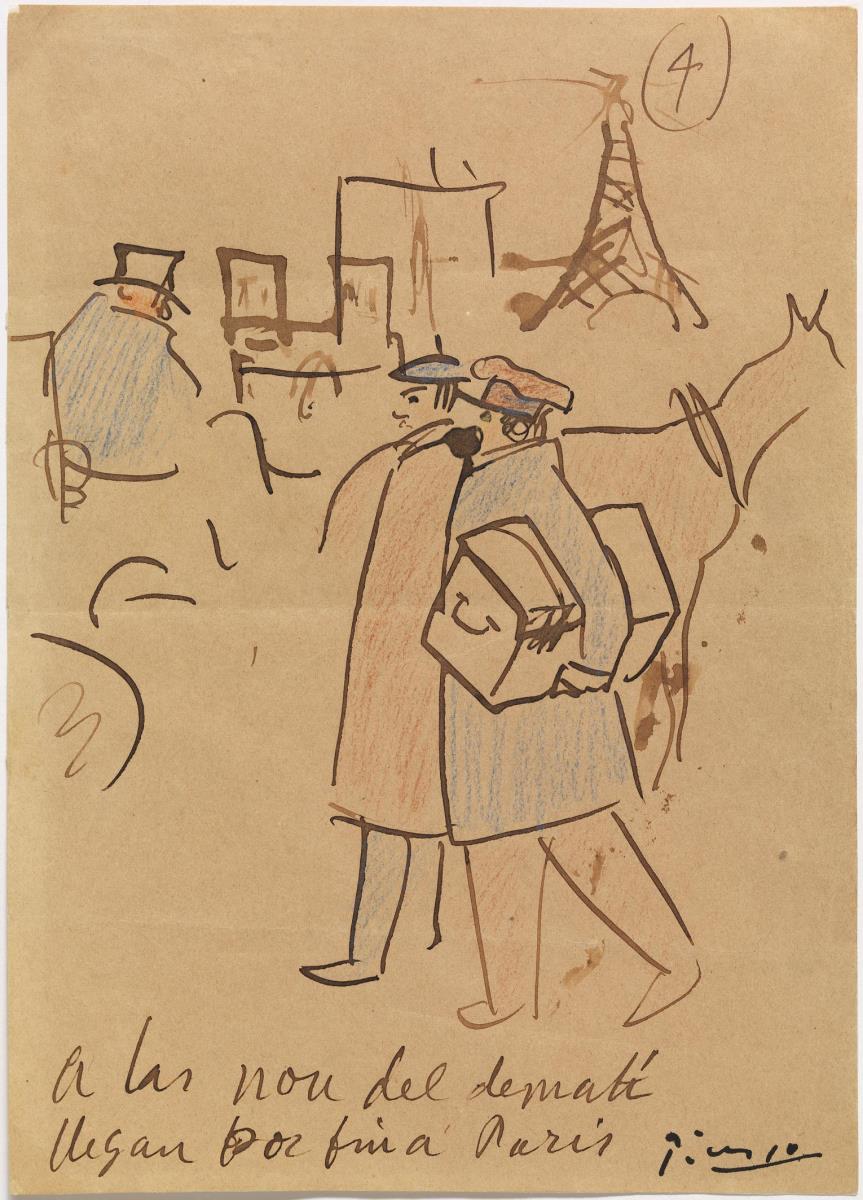

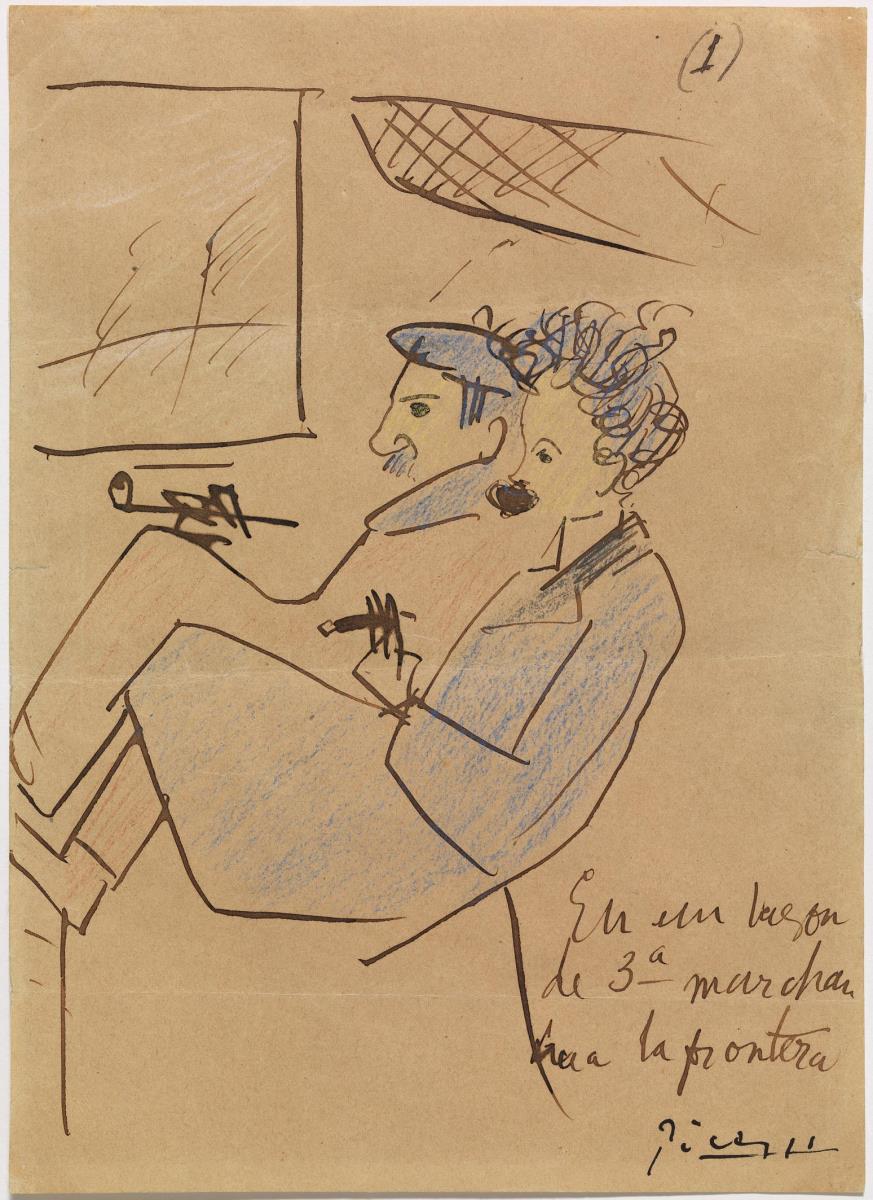

Picasso also resorted to the self-portrait as a space in which to project his most intimate reality. These works have more autobiographical overtones than his previous portraits, and many of them were made on modest supports. In contrast with the miserabilist archetype associated with his Blue Period, we now discover a number of openly erotic self-portraits, some of which are set in brothels or feature a procuress. On the other hand, the self-portraits linked to La Vie, his masterpiece of this period, are characterised by Symbolist traits. The narrative connotations of some self-portraits, such as his anecdotal drawings of his trips to Paris, form a sharp contrast with the formal research he made of the face during his stay in this city. The year 1901 is represented by four works, comprising one of the most outstanding sequences of portraits, ranging from mundane compositions such as Picasso in a Top Hat to other more introspective works like Self-Portrait (Yo), kept in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. During the next few years he would pursue his studies of the face, which culminated in his works of the years 1906–1907.

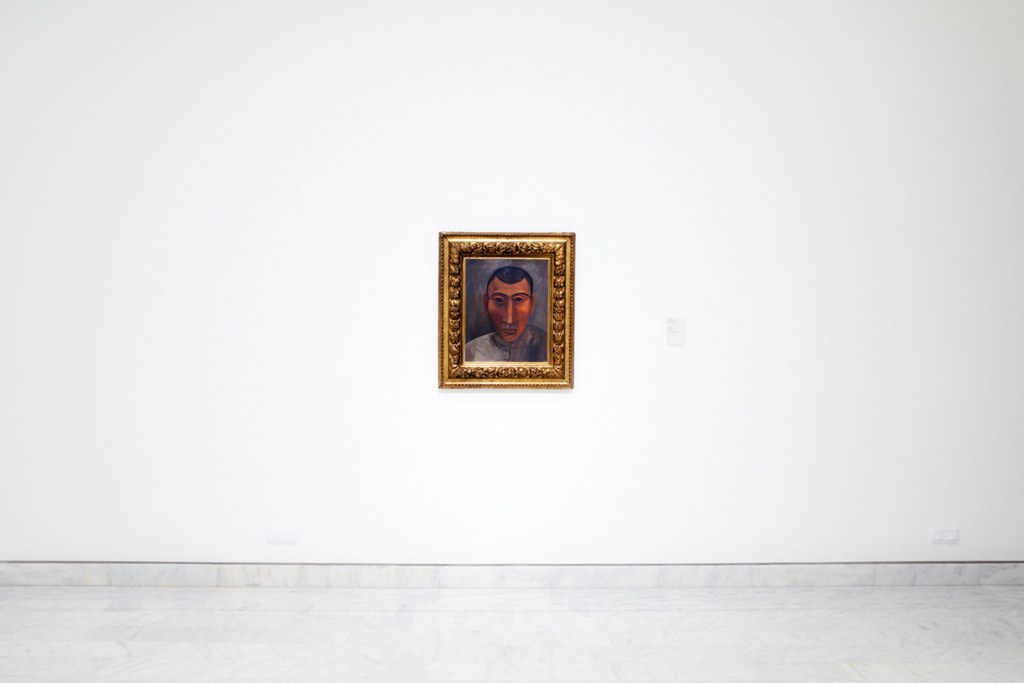

Paving the way to the mask

Picasso's production prior to 1907 was crucial in his career, for it coincided with the storm of modernity symbolically established in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The assimilation of new references and the continuous development of his pictorial language were translated into his self-portraits. His depictions of himself as a bohemian and a Harlequin made between 1904 and 1905 are a caesura that marks his distancing from the imitative quality of the genre. In 1906 the process that led to his primitivising style and his interest in ancient art, particularly Iberian, would be summed up by his simplification of shapes and masking of the face. The year 1906 proved to be a critical year in which Picasso produced a number of works that shared stylistic traits, as exemplified by the iconic 1907 Self-Portrait in the Národní galerie, that heralds a new pictorial language and is a prelude to the disappearance of the traditional self-portrait in the years to come.

The photographic self-portrait

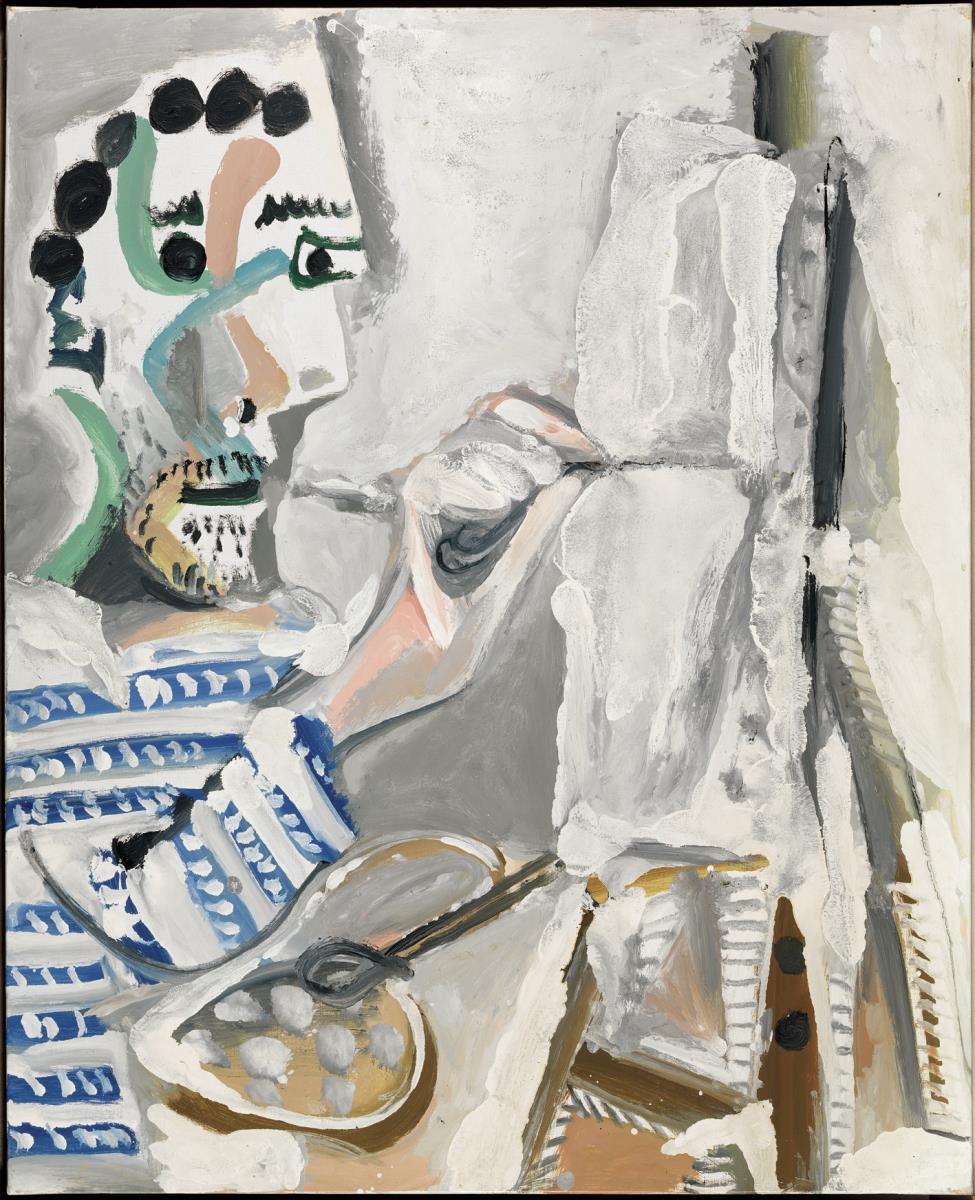

Picasso's interest in photography led him to cultivate a new variation of the self-portrait – the photographic self-portrait. His initial experiments revealed a still incipient familiarity with the technique, which he would gradually develop. His early self-portraits were made in Paris in 1901, followed by others over the next few years, particularly during his Cubist period when the traditional self-portrait had all but disappeared. These works sought to document his production and to project the image of the artist in his atelier. Sometimes, however, the notion of the self-portrait refers to the construction of painstaking sets by the artist, regardless of the authorship of the photographs. Years later Picasso turned to pictures of himself taken by other photographers, and even in photo booths, which he used as supports for playful compositions he would then illuminate, as we frequently find in his mature works.

“Monsieur Ingres, c’est moi!”

The visual results of Picasso's primitivising tendency that we saw in his faces of 1906 and 1907 would reappear in the years 1917–21 based on the Neo-Classic features that had already begun to appear in his oeuvre. In Picasso, the 'return to order' implied by the recovery of classical aesthetic models during the second decade of the twentieth century was expressed, as well, by a return to the primeval technique of draughtsmanship. His self-portraits in oils would be the exception rather than the rule, and in his emphatic defence of drawing he often turned to Ingresque manners. In fact, Ernest Ansermet declared having seen Picasso greeting himself before a mirror, exclaiming 'Monsieur Ingres, cést moi!' In the 1950s, when he was asked about his last self-portrait, he replied that he had made it in 1918, 'the day on which Apollinaire died', an event that symbolised his moving on. The intimate overtones of his reply would be refuted by his subsequent production, although it concealed a trace of fact insofar as it would be a very long time before he would embark again on such a meaningful set of self-portraits.

Presence and absence

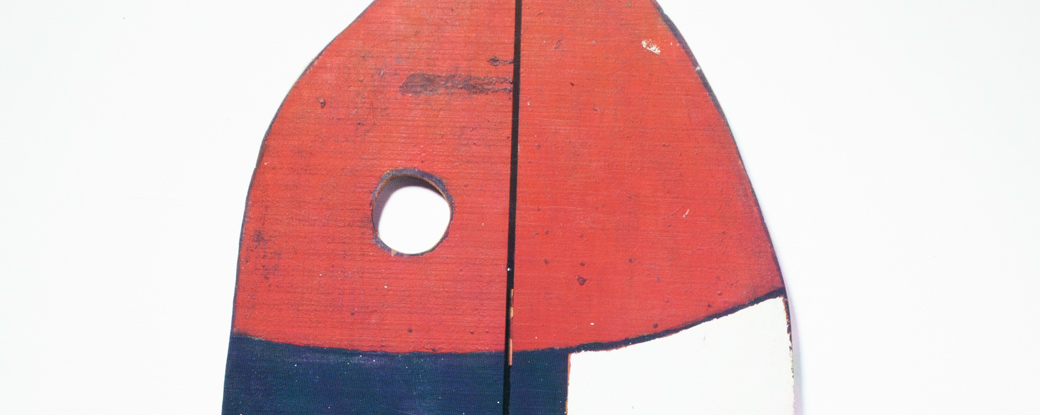

New forms of self-representation that were subtler and more cryptic began to appear at the time Picasso explored Surrealism. Such images of presence and absence would run through his self-representations for a considerable number of years. In the late 1920s Picasso embarked on a series of oil paintings in which the shaded profile of the artist is eventually confronted by a monstrous Surrealist figure. The shadow and profile would often be used as projections of domestic events he preferred to keep secret. In the early 1950s, the work The Shadow on the Woman, a metaphor of the breaking down of his relationship with Françoise who had left him, confirms the essential role of the shadow at times in which the artist was experiencing personal difficulties. With varying degrees of intensity, this resource would survive until the last years of his life, as the self-portrait genre extended to other techniques such as ceramics, prints and illustrated books, in which he even depicted himself as a writer.

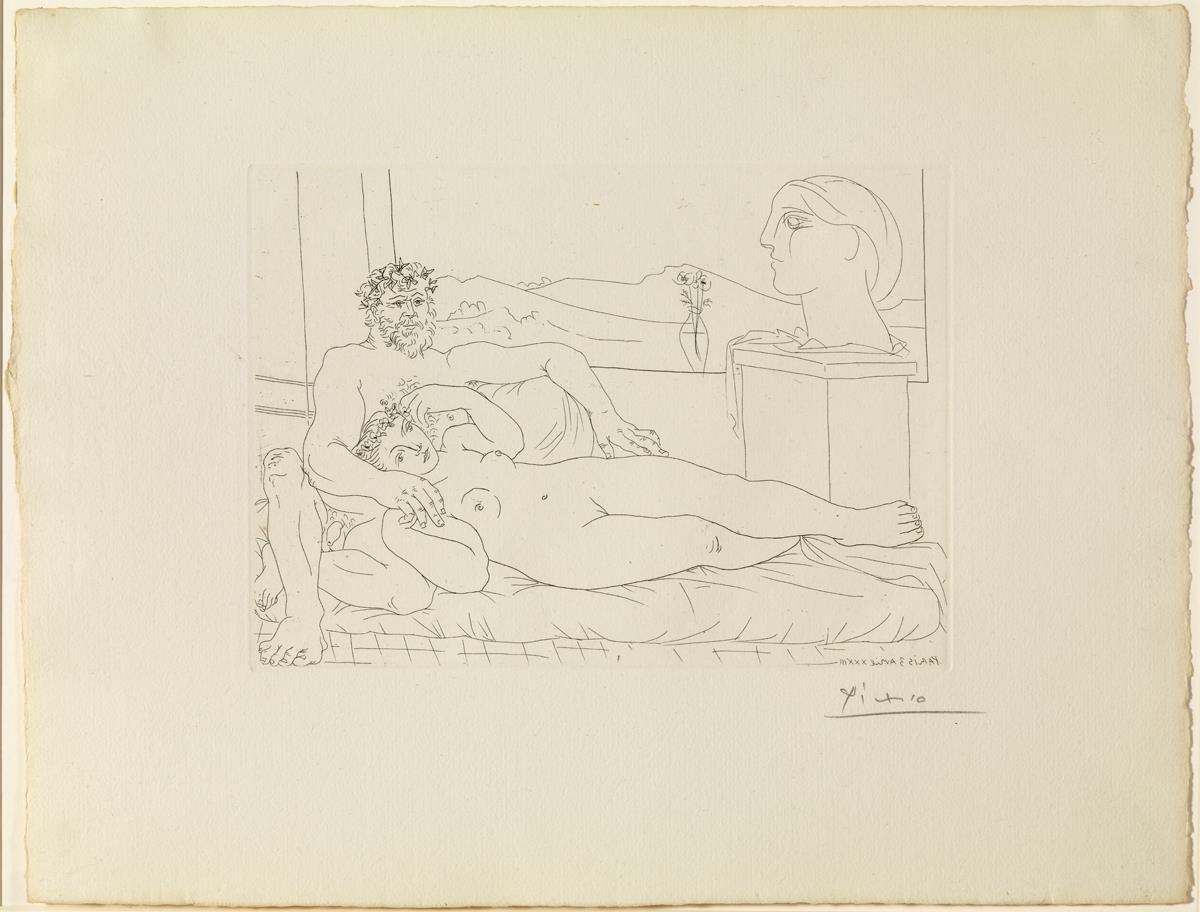

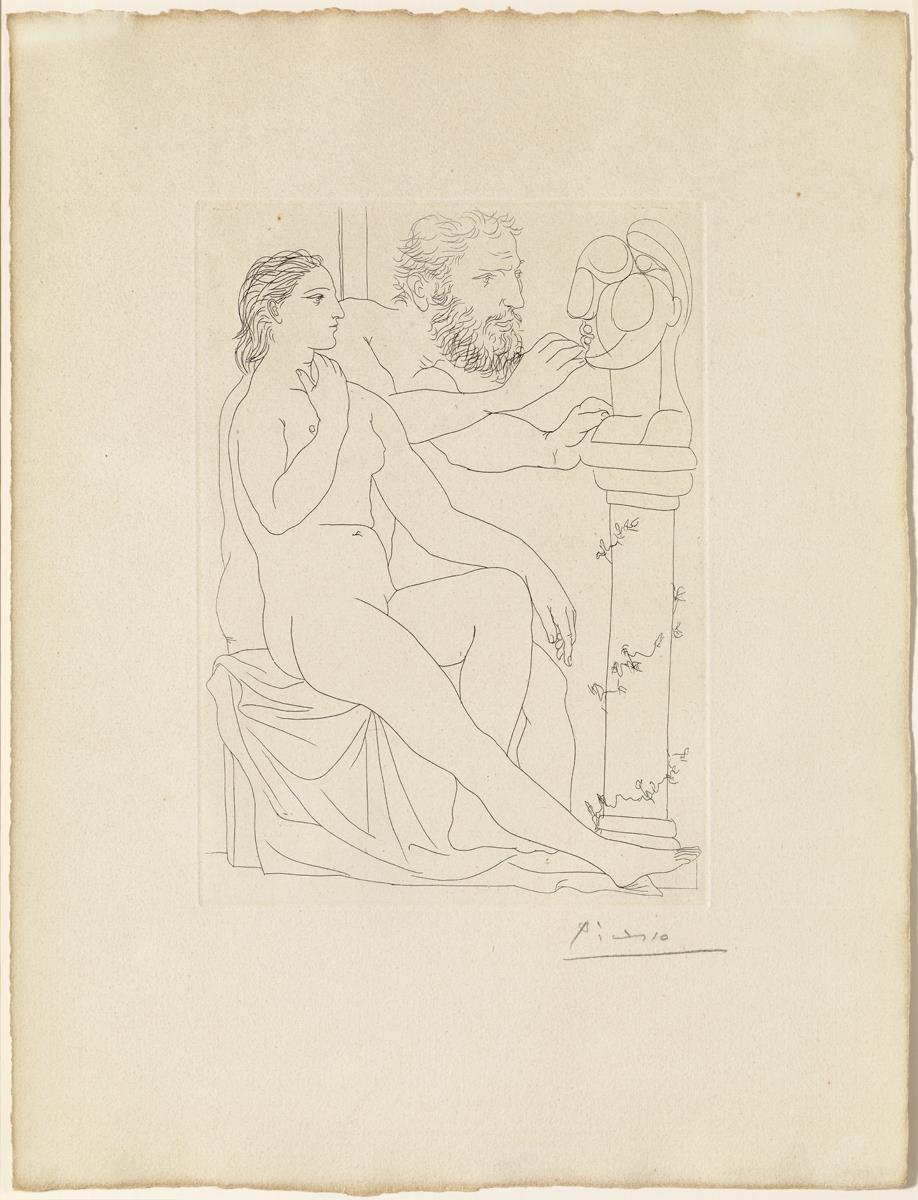

The artist and the model

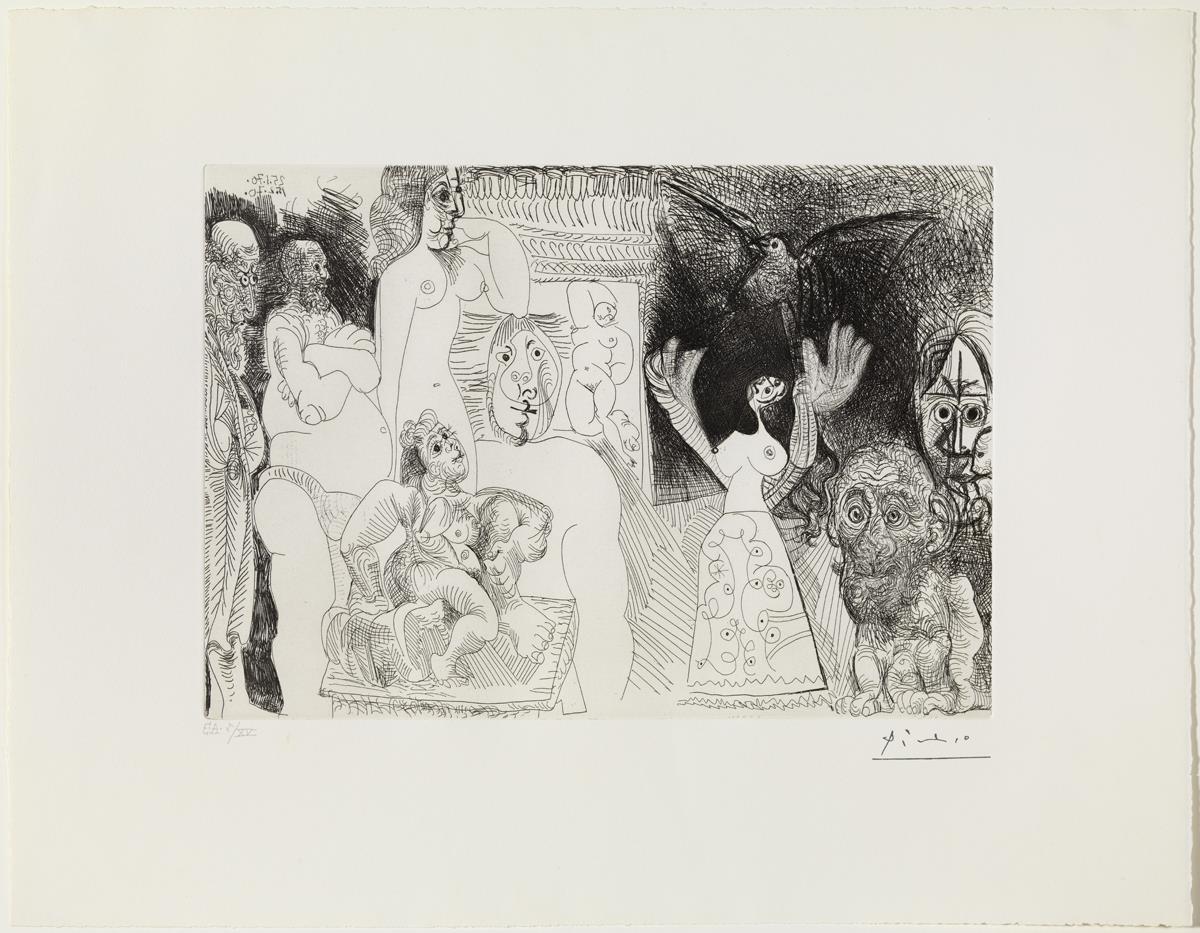

Michel Leiris considered the Picassian theme of artist and model as 'a genre in itself'. However, Picasso seldom represented himself with his own face, but turned instead to archetypes taken from artistic iconography in one of his classical metamorphoses that can only occasionally be deciphered in self-referential terms. For various reasons we know that the sculptor in Suite Vollard during the 1930s and the painter in Suite Verve in the 1950s had their biographical correlates. During the last years of his career Picasso insisted on the structural leitmotif of the image of the artist, which was in fact a sublimation of his own personality. Rather than the idea of portraying himself though, what inspired him was a desire to reflect on the image of the artist. Be that as it may, he was often deliberately ambiguous and we come across several kinds of self-portraits according to the degree of resemblance to his physiognomy: the explicit self-portrait (less common), the self-portrait with evocative features, and the symbolic self-portrait.

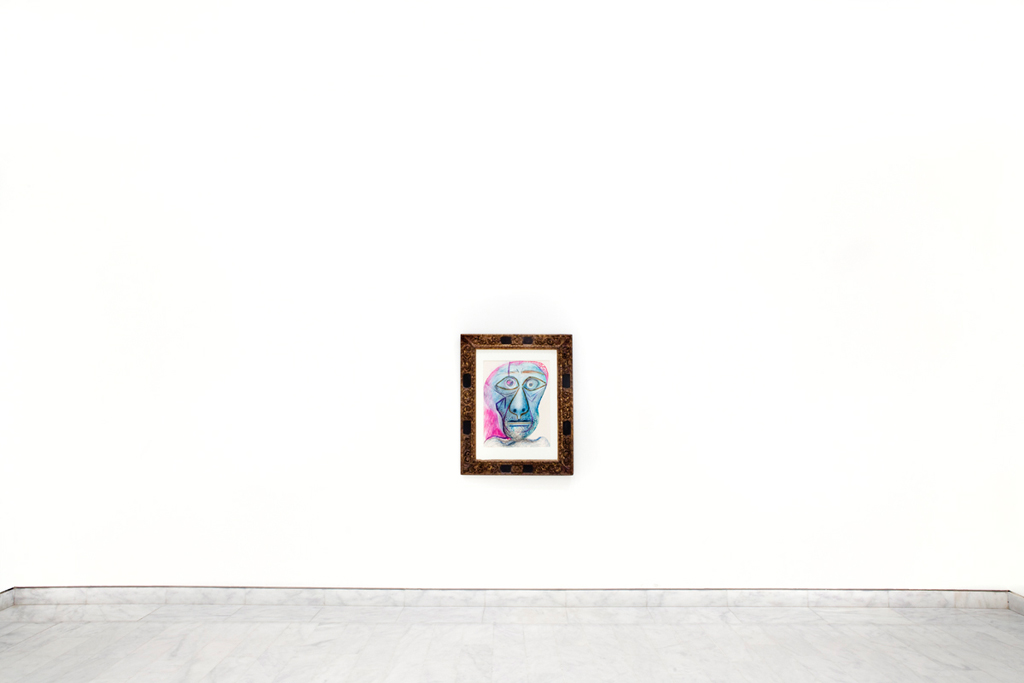

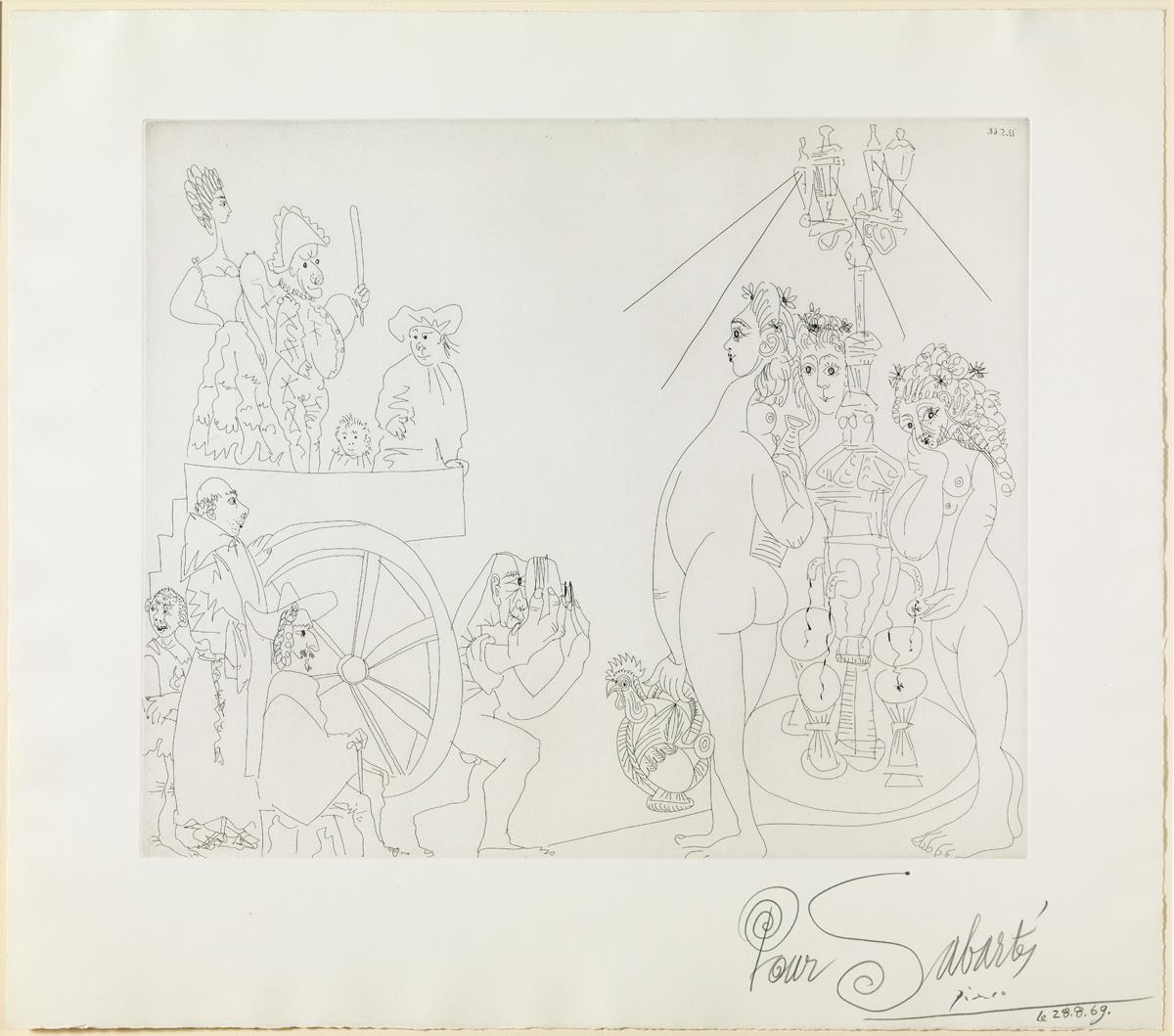

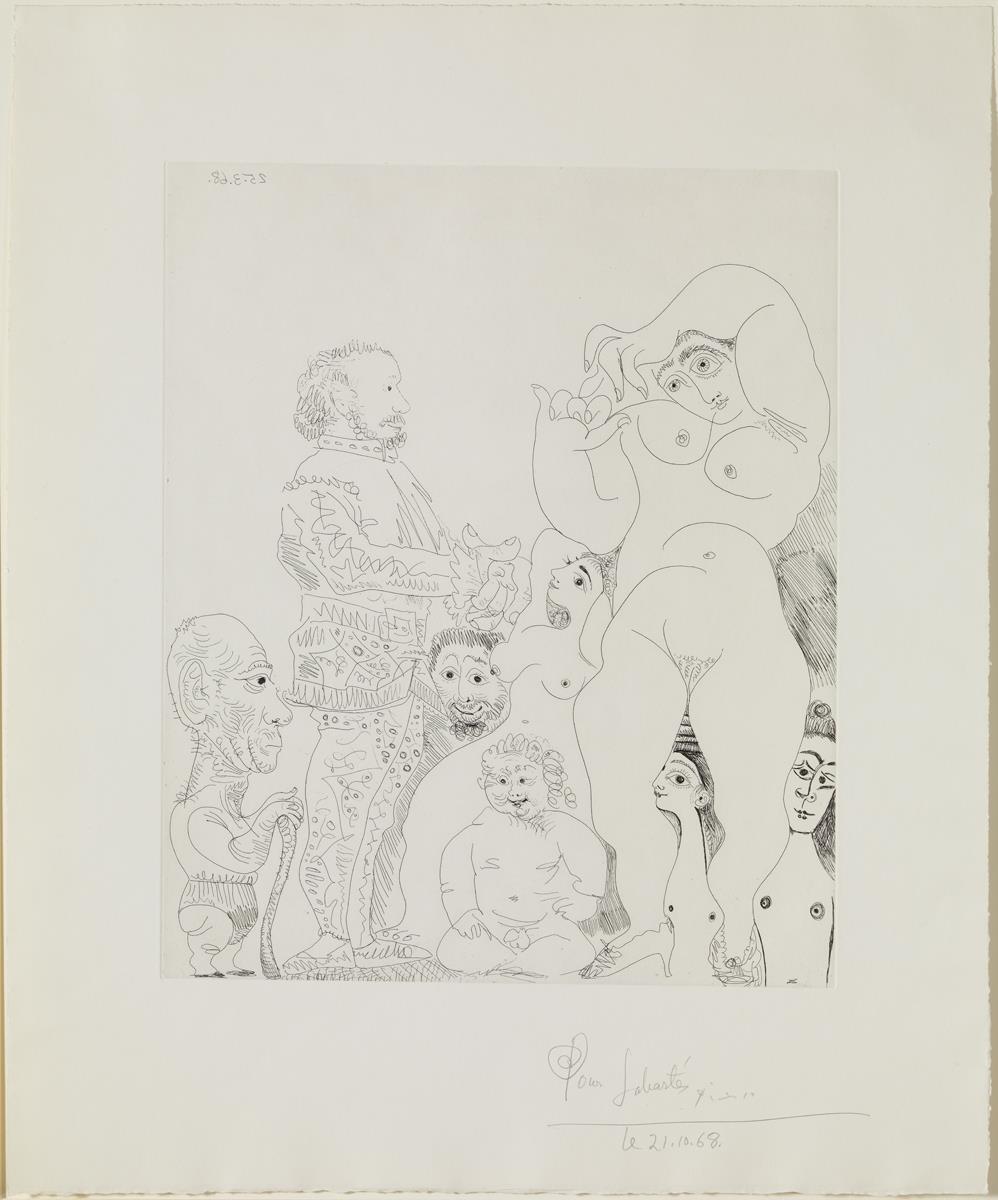

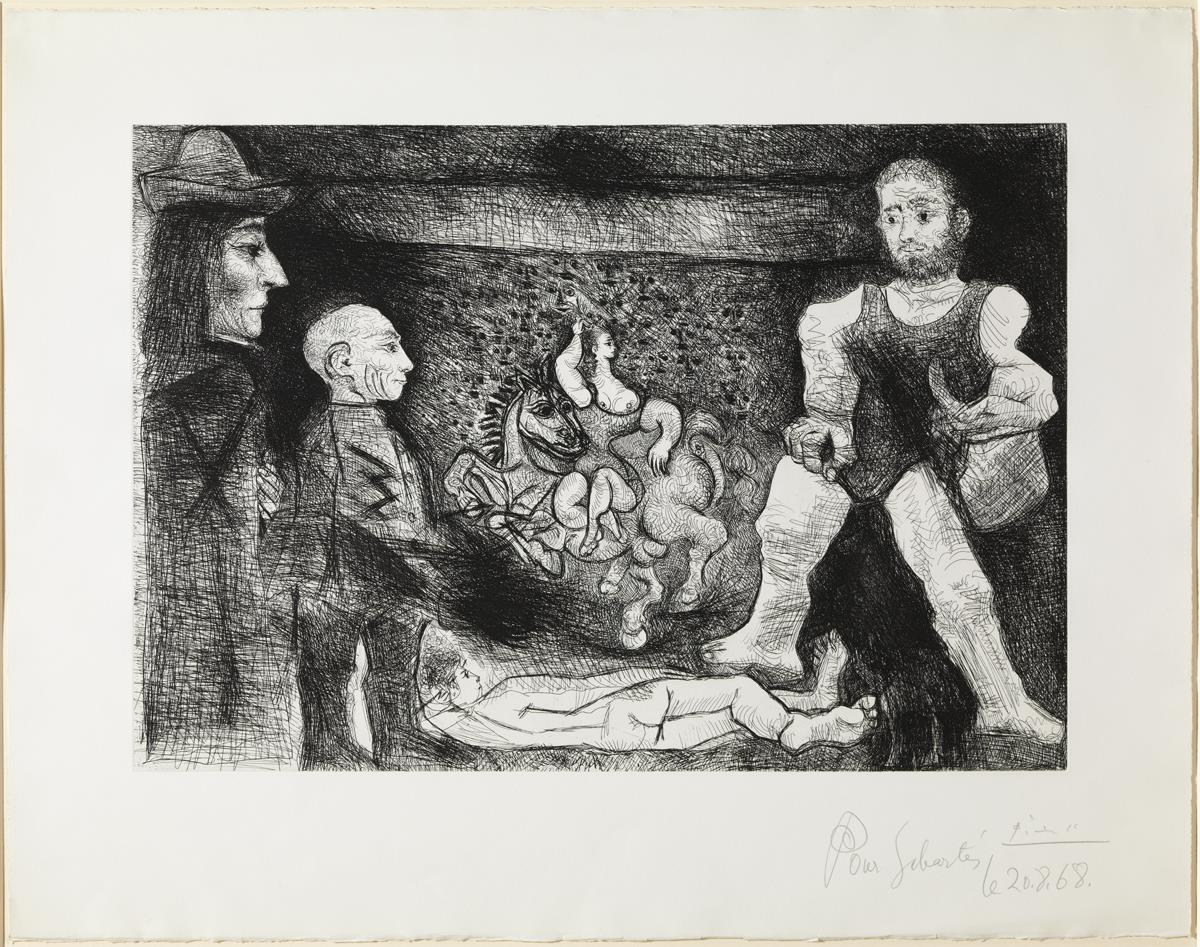

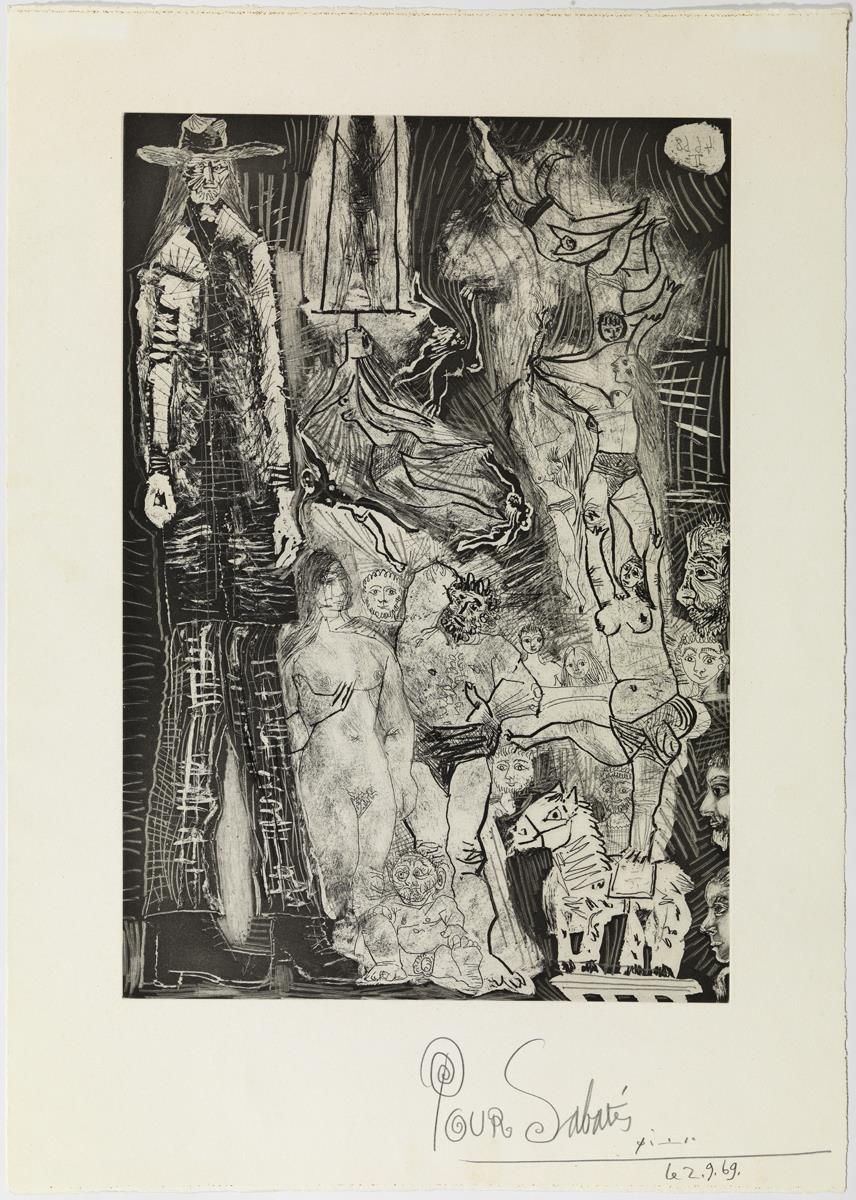

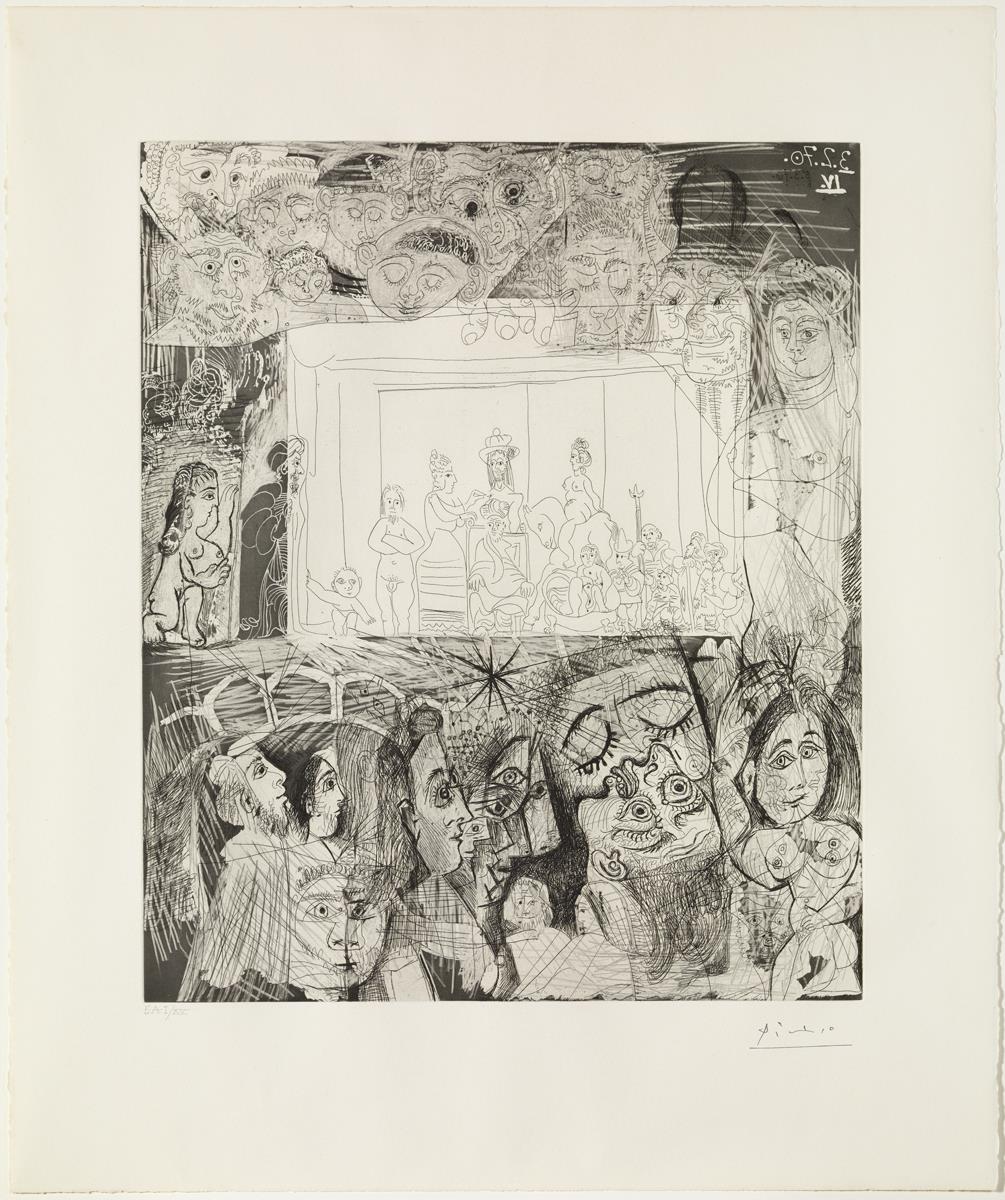

Painting against time

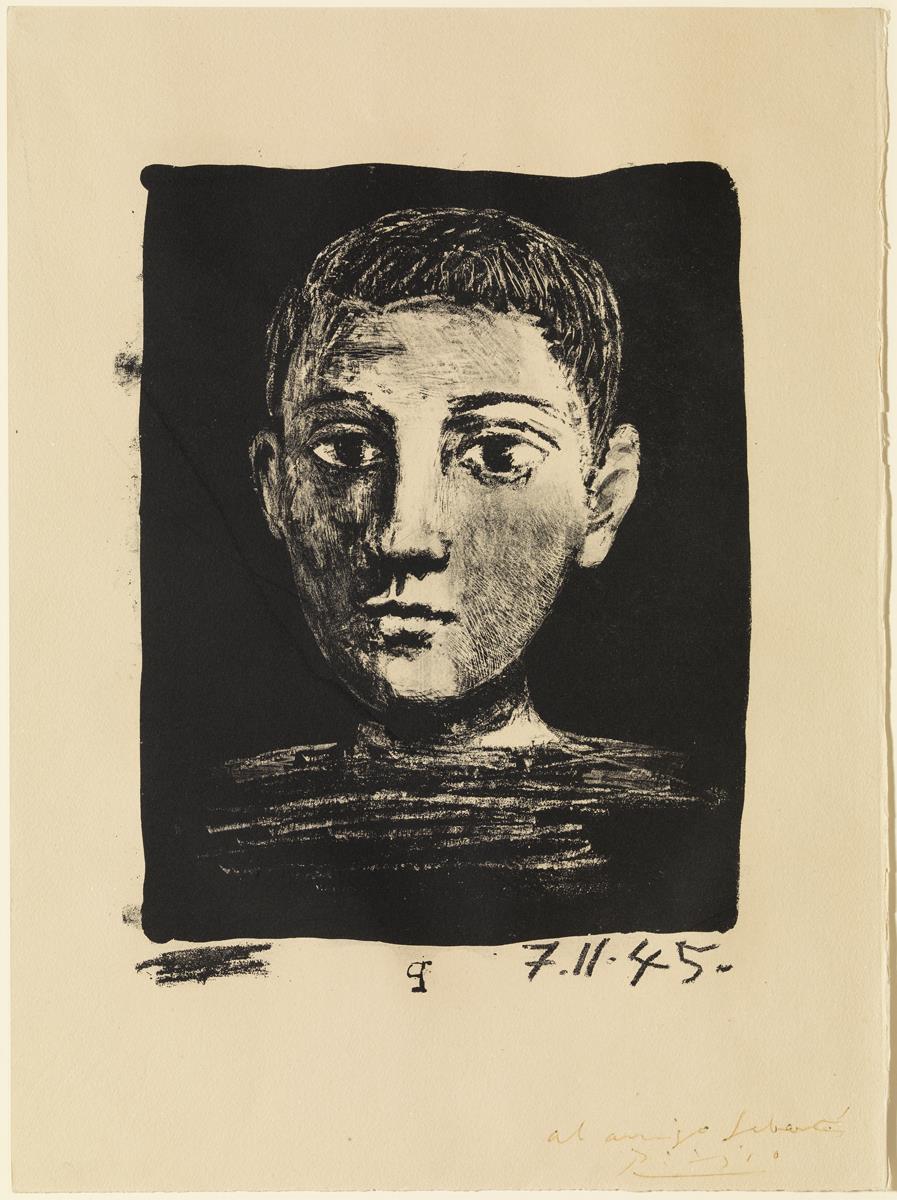

Picasso would revisit the self-portrait in his late works, chiefly prints, as a method of weighing up his life. In oils, the genre enabled him to display a remarkable degree of narrative in group compositions that embraced significant iconological content and multiple levels of interpretation. The most outstanding series of self-portraits belong to Suite 347 and Suite 156, made between the ages of eighty-six and ninety. Their iconography ranges from references to old masters and self-parody to the recreation of the world of the circus, the grotesque and the feminine – his theatrum mundi. The artist becomes a sort of spectator who recreates his own personal sub-world, adopting a number of different personalities including that of an impotent old man, a tourist and a newborn baby, and transcending by far the concept of self-portrait. In the summer of 1972, barely a few months before his death and in spite of his obvious physical deterioration, he insisted on bequeathing us a disturbing series of self-portraits that constitute the final expression of Picasso's legendary 'self'.